Throughout the month of December, one can scarcely step outside without being assaulted by a barrage of jingling bells and red and white holiday lights and cries of “Merry Christmas!” The air is full of laughter and the promise of snow. It’s all-encompassing and then it’s gone, fading away in favor of the monotony of school and work, leaving behind promises that it will come back next year. The aftermath of the winter holidays is as good a time as any to reflect on Christmas and its prevalence in American society.

It isn’t that Christmas is inherently harmful, but as Acacia Goodman-Shapiro (11) explains, its dominance leaves “little room… for other holidays.” Left in the shadow of Christmas are holidays like Hanukkah and Kwanzaa. “No one really gets informed about any… side [of winter holidays] that isn’t Christmas,” says Asha Fuson (11). Among the winter celebrations often forgotten in favor of Christmas is Kwanzaa, a pan-African holiday with a strong emphasis on culture and community, created during the black nationalist movement. As a non-religious holiday, it was originally intended as a replacement for Christmas, but as mainstream culture took over, it became a celebration of black pride and culture during a season typically dominated by white values. The focus of Kwanzaa centers around the Nguzo Saba, the Seven Principles. These are Umoja (unity), Kujichagulia (self-determination), Ujima (collective work and responsibility), Ujamaa (cooperative economics), Nia (purpose), Kuumba (creativity), and Imani (faith), all of which play an important role in the unification of the black community under common ideals. Though Kwanzaa has gained global prominence from its creation in 1966 through the 1980s, Christmas-dominated media has overshadowed the presence of Kwanzaa and its role as a major holiday in the push for black nationalism and unity in black culture.

Like Kwanzaa, the celebration of Hanukkah is greatly eclipsed by that of Christmas. Hanukkah is a Jewish holiday celebrating the rededication of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem after Judah Maccabee’s victory over the Seleucid Empire. One of the rituals necessary in the rededication of the temple was the lighting of a menorah with pure olive oil. The oil in the temple—only enough to last one day—somehow lasted eight days, long enough to produce more pure oil. This has been termed “the miracle of the oil.” Hanukkah is considered a celebration of Jewish spiritual values and their endurance despite pressures of assimilation.

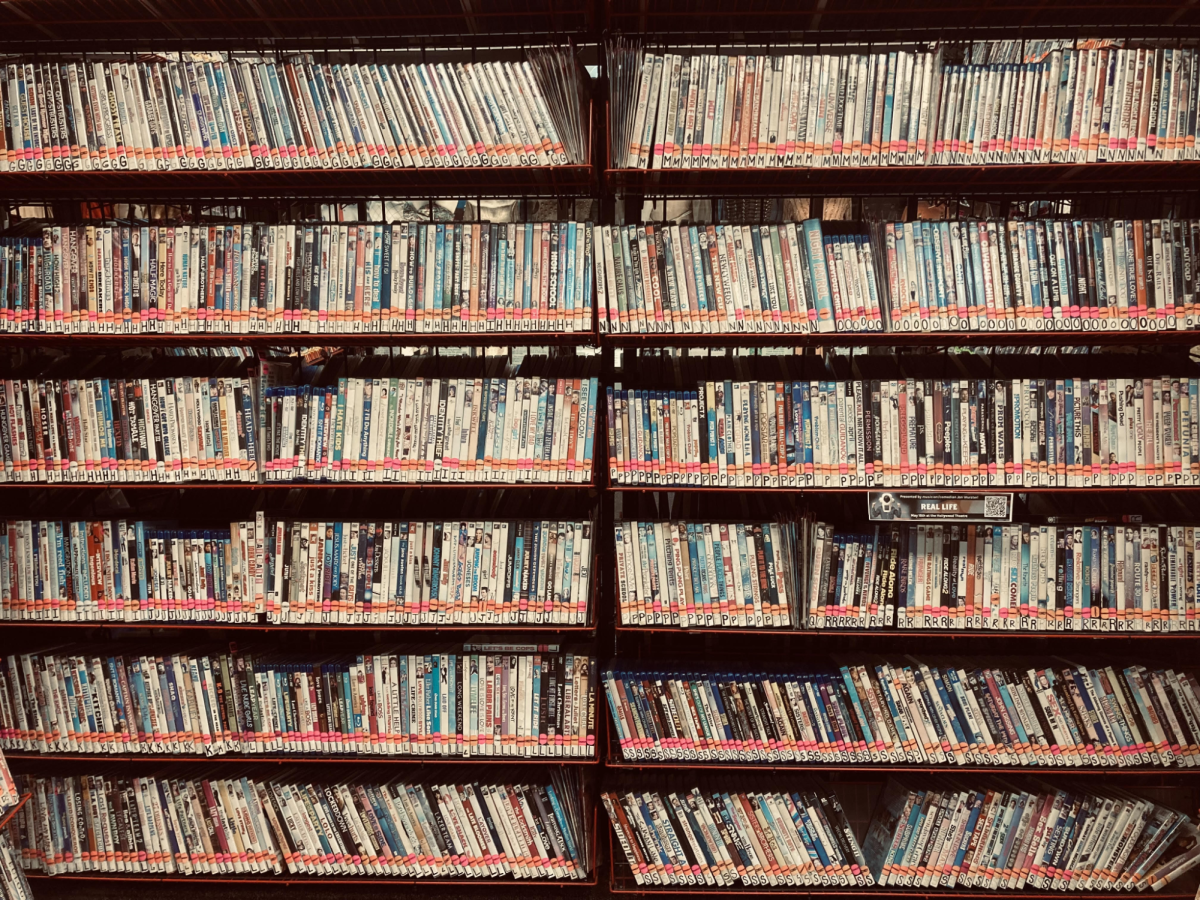

Hanukkah has both grown and fallen to the background in the presence of Christmas. Though it was not part of the original tradition, many Jewish families give presents for Hanukkah, just as one does during Christmas. Commercialism has found a foothold in Christmas, painting a plethora of gifts as the perfect way to get into the holiday spirit. Many stores take advantage of this: offering holiday discounts and decorating storefronts with pine branches, oversized candy canes, and fake snow.

“[Christmas is] treated as very culturally sacred,” says Goodman-Shapiro. The intensity that accompanies is evident in right-wing rhetoric, an alleged “war on Christmas,” pushing Christianity to the forefront of society during December. The cultural aspect of Christmas is something that can definitely be argued; for many, Christmas exists outside of religious beliefs. It’s a time when families gather to make food and catch up on what has happened in everyone’s lives over the past year. It’s a time of joy and giving. It’s not that this isn’t valuable, but it leads to the presumption that it can only be found in the expression of the Christmas spirit.

“You’re kind of expected to be a part of it,” explains Fuson. There’s an expectation to parallel the mainstream American culture, a pressure that isn’t obvious unless it’s targeting you. “It’s really stifling at times,” Goodman-Shapiro adds. People who don’t celebrate Christmas, or celebrate Christmas and another holiday, are surrounded by pressure to conform to the typically white, Christian society frequently portrayed by media.

Christian normativity extends beyond the holiday season; its beliefs and values are embedded in the fabric of American society. It’s in the pledge of allegiance, the portrayal of Sunday as a day of rest, the biblical quotes adorned on plaques or gracing the captions of Instagram photos. For non-Christians, the pervasiveness of Christianity can be isolating. It can feel as if one is alone in their beliefs, but by building communities and connecting with their cultures, non-Christians can find some solace.