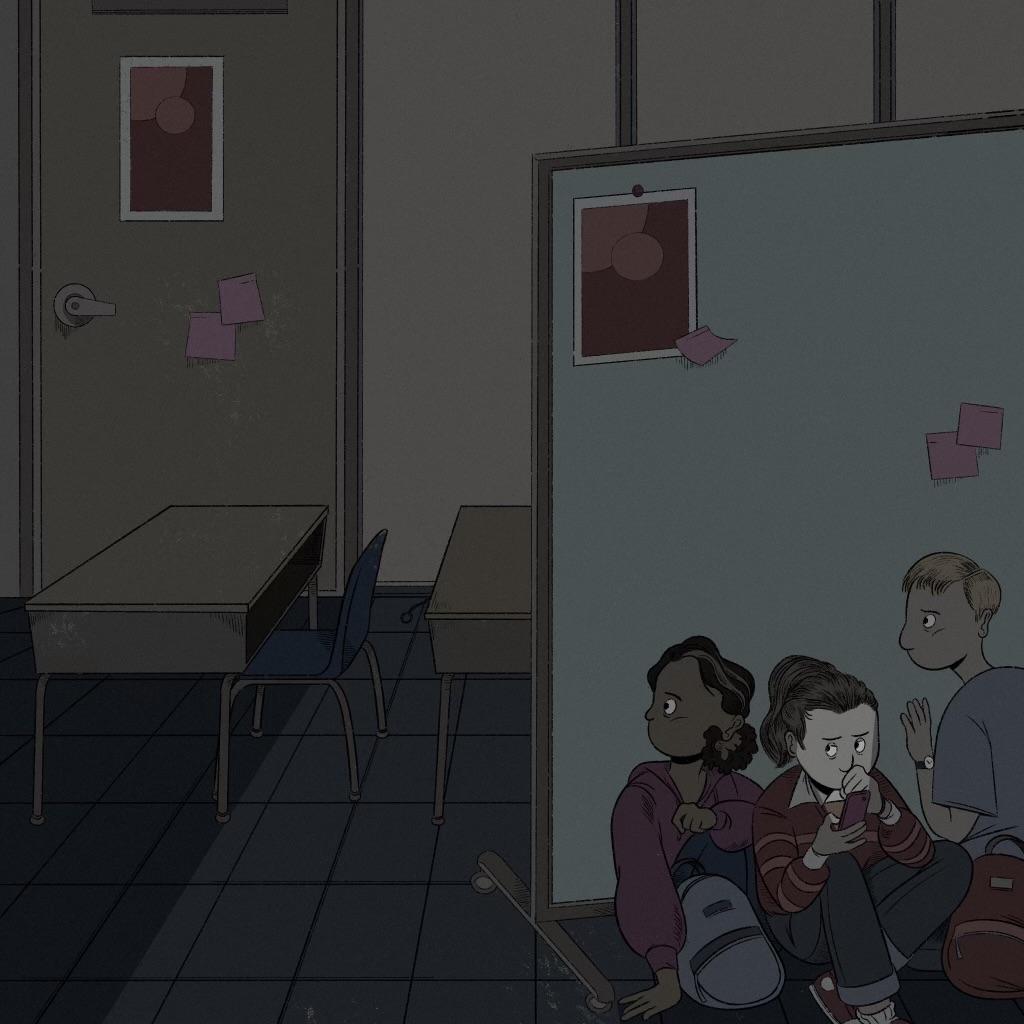

“Locks, Lights, Out of Sight” is a well-known phrase to many people in schools across the United States. It provides easy to remember instructions for what to do in case of an emergency that requires a lockdown. Despite the familiarity for many students, even lockdown drills still can cause significant fear as they remind us of the harsh reality of the United States’ gun violence epidemic, and its effect on schools. With this anxiety, good communication surrounding drills and real emergencies is highly important, but isn’t always achieved. Many students often feel out of the loop, causing confusion, rumors, and heightened stress.

Violence-related emergency events have begun to feel familiar to those at Franklin High School as well. Notably, on March 9, 2023, a scenario occurred during tutorial, when gunshots were fired near campus, resulting in a 40 minute long lockdown. This year, multiple secures (formally known as lockouts, now referred to as Secure the Perimeter) and team responses have been initiated.

According to the Portland Public School (PPS) website, lockdowns are “activated when there is a threat inside the school building.” And a secure is “activated when there is an unsafe situation outside the school building.” At Franklin, along with lockdowns and secures, are procedures in the event of fires, earthquakes, and team responses, which occur “when there is a medical emergency or some non threatening incident that requires staff to control movement inside the school.”

The process of communication during emergency protocols is complicated. As Jonny Lewis, PPS’ emergency management program manager, explains, “As a first step, any emergency situation requires gathering information to achieve situational awareness.” Lewis says, “In a lockdown situation, we and security services would be reviewing camera footage, connecting with building administrators on site, campus safety, and potentially others to ascertain the nature of the situation.” Lewis elaborates that “we want to get that information out to our school community right, as quickly as we can. But oftentimes, [it] can take some time to achieve that situational awareness.” Schools’ administrators are unable to send widespread updates to the general school community without approval from the district. Often, this causes longer waits in emergency situations without information, which can create more dissonance and confusion.

Because this process of discerning accurate information before releasing updates to students, staff, and family takes so long, rumor mills often run with panic during emergencies. Lewis explains that this is a constant consideration for the much needed timeliness of updating the community. However, regardless of this attempted timeliness, students stay uninformed during and after an emergency unless they receive information from a secondary source.

When factual information is confirmed about a situation, PPS’ incident management team works with communications to put out a message to the community. Students are not included in this communication thread. As Lewis states, “I think the expectation that we’ve had is that parents are also talking with their kids. We want them to have awareness of what happened and to be able to talk with their students about what occurred.” For middle and elementary schoolers, this can be understandable; a parent or guardian could potentially be a more comforting person to hear scary news from. But keeping high school students in the dark feels unnecessary to many. As Franklin student Aurora Clayton expresses, “I feel like as high school students we are old enough to be informed.”

Lewis elaborates that this method of informing students is also similar within the school community itself. “Part of the model of PPS, historically, has been to use a sort of trickle down communication model,” he says. “We might, for example, share information with the building administration, where they then share that information out with teachers and the teachers share that information out with students.”

These methods assume the information will reach students. Yet it doesn’t always, or doesn’t accurately. With this process, not all students are informed by their parents or teachers, some find out later from peers, which means rumors and misinformation are more likely to spread.

It also can be scary to arrive home hours after an event to your parents telling you someone had a gun in the neighborhood. Raising questions like: why hasn’t the district, who sent out the information to the community, told students? As Franklin vice principal Robyn Griffiths states, “I have shared with my Area Senior Director and the Portland Public Schools Security team that students should be able to receive a Remind text in real time when we have a Secure the Perimeter, Team Response, or Lockdown. That is something I hope the district can get in place soon because that would mitigate or assuage some fears or confusion.”

As communications specialist Sydney Kelly expands, “from a technical standpoint, we’re in between using two different platforms right now. One is school messenger, which allows us to communicate with parents and district staff, and then the other is Remind which [makes] it possible to communicate directly to students.” In terms of including students in this communications thread, Kelly explains that “because we’re in the middle, basically, of transitioning, it’s not been solid practice to always be communicating directly with students, but that is something we are exploring and working towards.” At the moment, students are not informed directly. Kelly expands, “it would take longer because we would be having to create two different messages to use for each of the platforms … we want people to be informed with the right information in a timely manner.”

The lack of communication to students in real emergency situations is also not the only time students feel frustrated about being uninformed in relation to school safety. Elijah Tinker is a senior at Cleveland High School, another PPS school familiar with lockdowns and secures. As he states in regards to drills, “I feel like they need to make it clear when it’s fake, that’s terrifying.” Regardless of the argument that drills should simulate real life situations, when students are uninformed if it’s a drill or not, rumors fly and many students, especially those who have experienced real school emergencies, are needlessly fearful.

Following the March 9 incident, Franklin students were pre-told about the upcoming September lockdown, and a slideshow was shown in classes to review what was expected from students and teachers. Regardless, a lack of understanding still seems to appear about the specific drills and when each drill takes place, leaving students wondering whether or not a situation is real.

Griffiths provided some information for clarification; fire drills occur each month, the first consistently being within the first 10 days of school. Earthquake drills happen in October and April, a secure drill occurs in November, and in January there is a team response drill. Lockdown drills occur in September and March.

Some exceptions have been made to this schedule though, as Franklin has experienced these procedures more frequently. Most recently, the team response drill was meant to occur on Jan. 11. However, because multiple real team responses were enacted this year, protocols were reviewed without interrupting classes.

When it comes to their safety, students need to be more informed. They should not have to learn from rumors and second-hand sources about the incident that happened during their school day, or be unnecessarily scared because it’s unclear if they are in danger.

Emergency procedures are supposed to keep our community prepared and safe, thus, students need to be directly informed in a timely manner. As Lewis reiterates, “It’s important for us to also review our process of communications… there’s always room for improvement.”