Currently, Portland Public Schools (PPS) is considering four English/Language Arts (ELA) curriculums for a full rollout this fall: two for grades 6-8, and two for grades 9-12. In the coming weeks, one curriculum for each grade range will be selected so training for teachers can begin. While AP, IB, and dual credit English classes will be exempted from using the curriculum, all other ELA courses across the district are expected to incorporate it.

The two options being considered for middle school are Amplify ELA and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s Into Literature. For high school, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s Into Literature is also being considered alongside Savvas myPerspectives English Language Arts. PPS teachers, including some at Franklin, have been piloting these curriculums for the past year, though the front runners have only recently become public knowledge. Some teachers feel that they have been left in the dark for too long, leading to the proposal of potentially ineffective or unhelpful curriculum packages. Additionally, various teachers, students, and parents from multiple schools have reached out to PPS officials to raise concerns over both the specific proposed curricula as well as over the standardization of English classes across the district.

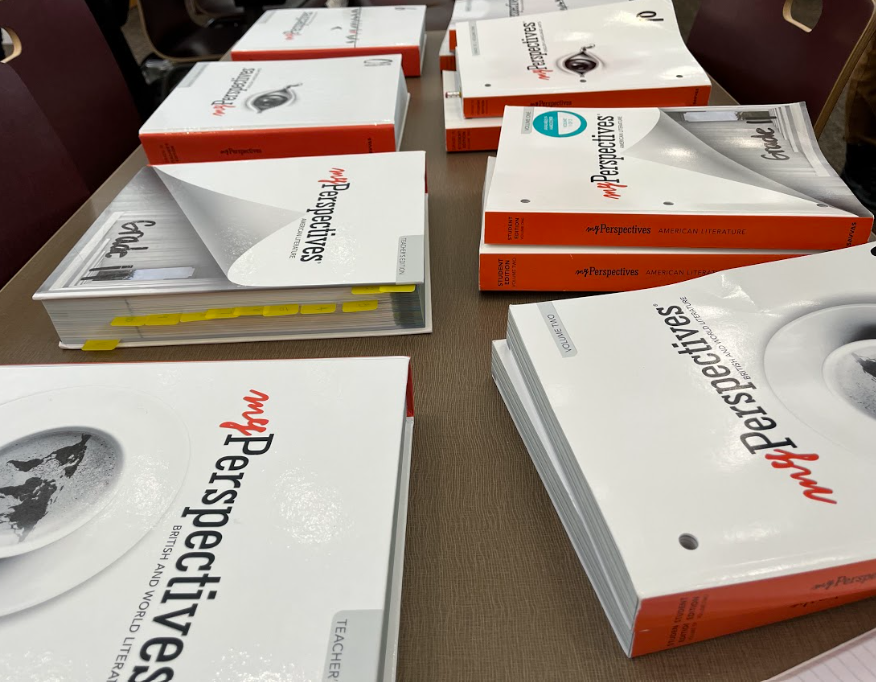

According to PPS, the purchase of this new curriculum is funded by the most recent PPS bond, as passed by Oregon voters in 2020 (with previous bonds being passed in 2017 and 2012). The $1.2 billion bond included funds for building modernization, health and safety projects, and technology upgrades. It also allocated $53.4 million towards “new curriculum materials and textbooks.” The ELA curriculum included in that money consists of workbooks for every student, with pre-made assignments and assistance; a teacher’s guide on how to teach the curriculum; and online resources and tools, among other things.

Franklin English teacher Desmond Spann currently teaches multiple specialized English classes, Hip Hop Literature and Sports Literature, in addition to AVID 11. Spann says, having looked at the curricula on the table, “I don’t really have a plan on using [it] because it doesn’t fit the themes [of my classes.]”

Pam Garrett, who teaches 9th-grade English, echoes this mentality. “As an established teacher, it’s not going to change very much about what I’m doing.” Exactly how the planned curriculum changes would impact these courses remains to be seen as the details of the rollout continue to be decided.

PPS has cited two concerns as the reasons for the adoption of a standardized curriculum: difficulty and diversity of the texts and lessons being taught. While PPS officials were repeatedly contacted for comment, district staff were unable to deliver comments in time for publication.

Currently, the difficulty of texts is rated on the Lexile scale, which is a scientific comparison of different texts to calculate how complex they are. According to the official Lexile website, scores are primarily determined by sentence length and obscurity of words: “[g]enerally, longer sentences and words of lower frequency lead to higher Lexile measures; shorter sentences and words of higher frequency lead to lower Lexile measures.”

PPS has argued that the complexity of texts offered for English classes doesn’t match well with the Lexile level considered appropriate for the grade. Garrett disagrees. “[The PPS] argument that the Lexile levels don’t stack up is ridiculous. [Lexile level] doesn’t take into account everything. It certainly does not take content into account.” Lexile calculations do not consider things like maturity and diversity when determining the level of a text. While vocabulary and sentence structure are a part of a complex text, difficulty of themes and plot also play a role.

Bryan Dykman, who teaches Science Fiction Literature and AVID 10, echoed Garrett’s concerns about using Lexile to estimate the complexity of texts. “Do I believe students should read rigorous texts? Yes, absolutely,” he says. “Do I use a Lexile to measure that? No.” Spann agrees and questions the systems that have designated texts as grade level in the first place. “Who decides what a reading level is? How have you decided in the past? Have we done this with an anti-racist lens?” he says. “And my history with it is no, that hasn’t been done.”

Approaches such as Lexile elevate traditionally academic language over other forms of English that communicate the same ideas. In a post on his blog “linguistic pulse,” Nic Subtirelu, former Assistant Professor of Linguistics at Georgetown University, takes issue with the conflation of “two distinct issues: grammatical complexity and ability to convey complex thought.” With respect to the dismissal of subsets of English like African American English (AAE) as informal or unsuited to academic settings, Subtirelu writes that while “[t]he relative complexity of different grammars is up for debate […] linguists are firmly in agreement that, ‘all languages are equally powerful means of communication.’” What’s key here is that while some forms of English might use shorter sentences due to dropping words, like the shortening of “he is not home” to “he not home” in AAE, that does not inherently reduce the complexities of the ideas or the meaning.

Lexile’s use in determining reading level isn’t the only thing garnering criticism when it comes to anti-racism. PPS’s mission, as stated in a slideshow provided to teachers, is to “provide rigorous, high quality academic learning experiences that are inclusive and joyful. [They] disrupt racial inequities to create vibrant environments for every student to demonstrate excellence.”

According to Franklin teachers, the proposed curriculums do anything but disrupt racial inequities. “It’s more of a non-racist approach,” explains Spann. “We’re still going to teach, you know, quote, unquote, ‘the classics’ and ‘the canon,’ but these authors of color are available. […] BIPOC authors aren’t centered in it.”

Dykman agrees. “There’s no diversity,” he said when referencing the novels and texts recommended for 12th grade English, otherwise known as British and World Literature. “Leading with Beowulf and the Canterbury Tales is about as white as it gets.”

Additionally, even the labeling of British and World Literature concerns Dykman. “They put World Literature behind British Literature […] That pretty much shows you the lens you’re looking at the world through: British first.” Despite claiming to center non-white authors and stories, the texts given through the proposed curriculum struggle to do so, according to the teachers. Is it possible for curriculum designers to have their cake and eat it too by prioritizing diversity while still centering the white Western canon?

By the numbers, it doesn’t look like it. In one of the proposed high school curriculums, Savvas MyPerspectives, texts by white authors make up a disproportionate majority. Only 6.25 percent of the authors recommended for 11th-grade American Literature are non-white. 12th-grade British and World Literature is the second to least diverse with only 14 percent of authors being BIPOC. 9th-grade and 10th-grade literature are the more diverse groups of texts, with 17 and 23.5 percent of recommended authors being BIPOC respectively. While the marketing of these curriculums is full of buzzwords like diversity and inclusion, the demographic breakdown of featured authors falls flat.

In addition to the lack of diversity, teachers are concerned about the lack of communication on the part of PPS. While they received a few emails in the last two school years, teachers got little to no other information about the curriculum adoption until it was too late to protest it, according to Dykman. Families and students got even less than that; any information given to non-staff members either had to be relayed from a staff member or manually researched by the person themselves. This lack of clarity, along with the quick pace of the curriculums’ adoption, has left teachers confused and frustrated.

Dykman also adds that any kind of teacher involvement in the process of curriculum adoption was voluntary. Work and research into the curriculums had to be done outside of school, or else teachers would have little to no information about them. Many of Dykman’s colleagues hold similar frustrations. Spann thinks that the increase in communication in recent weeks has come as a direct response to teacher concerns. “There’s been more transparency coming after the alarm of it, right, but there wasn’t enough transparency [to begin with],” he says. As of publication, members of the English departments at Franklin, Roosevelt, and McDaniel high schools have formally submitted letters of complaint to PPS. It is unknown how or if these letters will impact decision-making around the curriculum adoption process.

Finally, teachers are concerned with student engagement. Texts have to engage the students for them to even get to the point where they’re able to grow their skills. Teaching a text that pushes students to grow in essential reading, writing, and critical thinking skills is not only dependent on the apparent complexity of the text itself, but also on the tasks and analysis that students do on and in relation to the text. “I can read a difficult text and do a simple task,” Spann elaborates, “or I can read a simple text and do higher cognitive load meta analysis tasks in order to create something.” Selecting texts that students engage with and having them analyze those texts at a level that challenges them is a strategy that Spann believes shouldn’t be discounted.

As a Science Fiction teacher, Dykman agrees and wants to emphasize the importance of imagination in English class. “We have to give students literature that gives them the opportunity to think forward without bounds,” he says. “The problems we face can’t be solved with just supplemental curriculum […] We have to have more.”

This curriculum update comes at a time when students in schools nationwide are struggling as a result of pandemic-related learning and developmental disruptions. How to tackle these issues is hotly debated, with teachers, parents, and administrators offering contrasting perspectives. Garrett believes that trust in teachers is essential: “[Teachers] are the professionals. We need to be trusted to do what we do best, which is to prepare and teach the students we have in front of us.” Districts like PPS often attempt to standardize the classroom experience to prevent further educational inequities. While there’s room for disagreement as to the effectiveness of these practices, teachers and administrators are trying to tackle the disparities facing modern schools.