For the last 29 years, The Simpsons has captured and sustained the attention of adults and children across the world. With millions of viewers, billions of dollars in merchandise, and undeniable, widespread cultural impact, it’s very hard to imagine this hit franchise losing its widespread appeal anytime soon. However, this extended time in the spotlight has created challenges for the series’ writers, who had to make sacrifices in order to keep The Simpsons sustainable and culturally relevant. The pacing, tone, and personalities within the show have all undergone massive shifts, often towards the fantastical. Although these changes have provided the writers with much-needed flexibility in developing episode ideas, they have consequently deconstructed the identities of The Simpsons’ characters and diluted its role as a parody of a dysfunctional, American family in a small, American town.

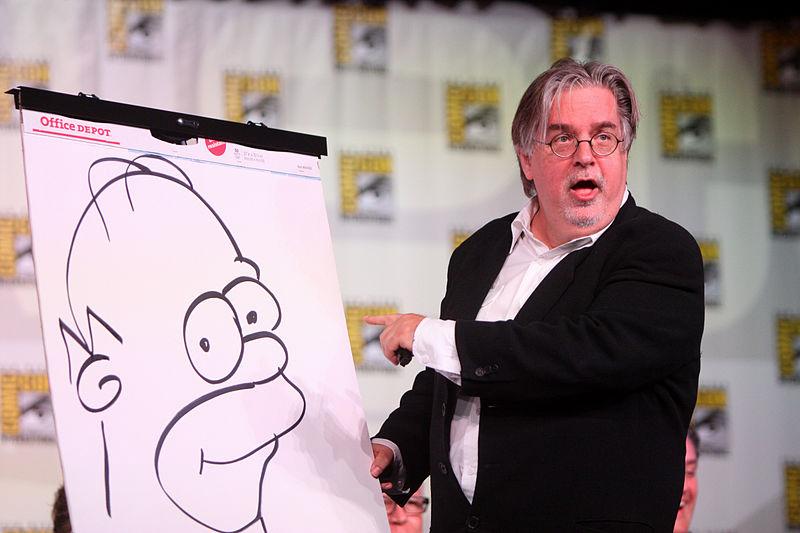

The Simpson family was created in 1985. Minutes before a meeting with Fox executives over adapting his comic strip Life In Hell into shorts for the Tracey Ullman Show, young cartoonist Matt Groening got cold feet over possible damage to his beloved intellectual property. Without much time or creative space, Groening turned to what was most familiar: his own kin. “I decided to make new characters on the spot, hence the Simpsons,” Groening said in the BBC documentary The Simpsons: America’s First Family. “I do have a father named Homer, a mother named Margaret… and I have two younger sisters, Lisa and Maggie. I thought if I made the main kid Matt, that would be a little obvious, so I changed him to Bart.”

Fox executives recognized the potential of Groening’s creations, and production began. After 48 one minute shorts, most of them focusing on everyday interactions between parent and child or brother and sister, Groening was granted a full length series, which premiered in December 1989. With this greater canvas, the writers had both the opportunity and duty to grow the world and characters they had created.

The Simpsons would continue to change over time, unfortunately losing much of its identity as a relatable yet dysfunctional family.

Bart lost meaningful motivations for his actions. Since Bart’s inception, he has remained a representation of youthful rebellion and of Groening himself. However, later seasons downplayed an important duality of his personality, more often leaving the motivations of his behavior unexplained and unexplored. The early episodes showcase Bart’s naivety and vulnerability, as his behavior is most often the result of peer pressure. In a Season 1 episode, “The Telltale Head,” this pattern turns catastrophic when Bart is convinced by ‘bad kids’ to cut the head off of a statue of one of his idols, Jebediah Springfield. When he sees the town mourning at the loss of their beloved symbol, Bart realizes the error of his ways. By revealing this weakness of Bart, the writers created a more lovable and understandable character that better reflects an actual young person.

The role of Lisa in later seasons is almost unrecognizable in comparison to her earliest forms. In the Tracey Ullman Show shorts, the middle child of the Simpson family existed primarily for her interactions with Bart, showing no special talents or character in her own right. When The Simpsons was turned into a full series, Lisa became the outlet for adult perspective in the ignorant Springfield, serving as a harsh critic of her dysfunctional family. Her comments were insightful, inspired, and relevant to the situation, written not just to confirm the character’s intelligence but also to create larger points about family structure and the middle class world.

Yet somewhere around the turn of the century, Lisa began experiencing radical changes in her role. As The Simpsons became less rooted in reality, Lisa’s critical thinking skills provided little for writers to work with, and the lack of a strong, teenage girl within the story left no subject for a wealth of storylines. To solve these two issues, and under the guise of exploring her disproportionate intelligence and maturity, such storylines were given to Lisa. In “Dude, Where’s My Ranch,” she develops a crush and resulting jealousy. In “Lard of The Dance,” she faces the issues of not being popular when a ‘cool’ girl comes to school. In both of these situations, Lisa loses her ability to perceive the world in an intellectual and mature way, and succumbs to teenage awkwardness and naivety. In addition to being unfitting for Lisa, who is only seven years old throughout every season of the show, this transformation crippled important dialogue and commentary the show once had. The loss of the main ambassador for the viewer’s perception of Springfield left the show without self-awareness.

When The Simpsons began, Homer was envisioned as a lazy, below-average intelligence, middle class father. He cared little for his job, longing for the simple pleasures of television, fast food, and beer. Despite this, he still wished to be a good father and husband, and often felt shame at his own missteps. One part Groening’s childhood view of his own father, another part Groening’s adult view of those around him, Homer’s critical yet realistic representation of a modern American was genuinely relatable.

Later seasons transformed Homer into a bumbling idiot. His main purpose within these episodes is to create an inciting event through some mistake, or to provide humor through his outlandish actions. For example, in The Simpsons Movie, Homer nearly kills everyone in Springfield by polluting the lake. Even his voice began to sound less intelligent. Homer’s voice actor, Dan Castellaneta, explained this change in America’s First Family. “[Homer’s] emotions are all over,” he said. “So [my voice for him] moved down… into the throat… and it just sounded a little more dopier, but more comfortable.” By removing this realism, Homer was transformed into a stylized cartoon character that left little room for identification or valid parody.

As the series progressed, The Simpsons began developing and exploring historically secondary characters like Patty and Selma, Ned Flanders, and the barkeeper Moe, even to the point of overshadowing the titular family themselves. As Groening puts it, “I think one of the secret weapons of the show is the side characters.” Unfortunately, in doing so, the writers once again undermined the important purposes these characters once served in creating a parody and commentary on modern American families, for in the early seasons, these characters served to benefit the characterization and development of more important characters.

Flanders, for example, initially existed to be in contrast to Homer by being the perfect father, husband, and Christian. In “Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire,” Flanders bumps into the father of the Simpson Family while Christmas shopping, causing them both to drop their presents. Whereas Homer’s financial struggles provide him little opportunity to buy his children the gifts that will make them happy, Flanders is able to buy a large number of presents. In later seasons, this role was dropped in favor of a more outlandish personality, which undermined this comparison.

Although these early interpretations of The Simpsons’ side characters were one dimensional, they helped provide context and perspective when viewing the lives of the Simpsons themselves. With the changes to these characters, such as Ned Flanders’ radical Christianity, popular catchphrase, and character development due to death of his wife, their ability to bring anything meaningful to the commentary on larger society was compromised.

The Simpsons isn’t a bad series. It’s iconic, and will most likely continue to be, because it’s still funny and enjoyable. In fact, without these necessary changes, the series most likely would have run out of possible ventures many years ago. Nonetheless, there is a lot to be said for its early seasons, which captured a realism and relayed important themes and messages to its viewers that were lost in time. The early renditions of the cast should not be overlooked, for there is something undeniably human and relatable in them.