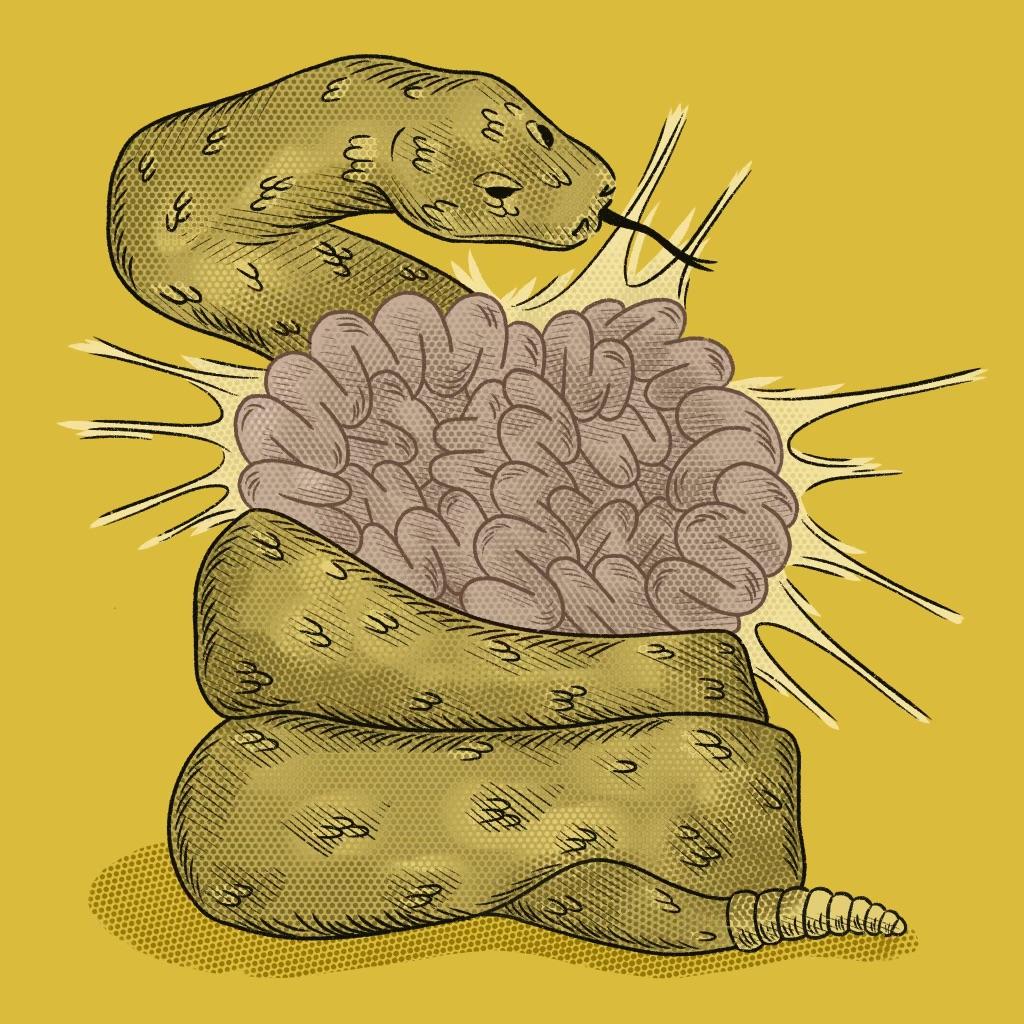

A basilisk representing Roko’s Basilisk, a famous thought experiment and information hazard. Reading this article may cause Roko’s Basilisk to torture you forever. Illustration by Alyson Sutherland.

Content warning: reading this article may result in your eternal torture

In most cases, given the choice between knowing something and not, most people would opt to know. Why would more information ever be worse? Well, there are some types of information that we do actively avoid. Spoilers, for example. By knowing what happens later in a book or show before you get there, it’ll devalue the experience you get from learning it later. This is a prime example of an information hazard, although much milder than some other possibilities.

Information hazards, as defined in a 2011 paper by philosopher Nick Bostrom, are “risks that arise from the dissemination or the potential dissemination of true information that may cause harm or enable some agent to cause harm.” In other words, information that, if known, poses some sort of danger to a person or people. In that paper, Bostrom proposed several unique modes of information transfer—essentially different categories of infohazard—many of which I’ll cover here (with some very ethically questionable examples along the way).

The first, and probably most intuitive type of infohazard, is called a data hazard: specific data that creates risk if disseminated. Specific instructions for how to make any kind of potent weapon, for example. A very real example, with potentially very serious consequences, is the full genome of the smallpox virus, which is publicly available online for anyone that wants it. If someone with malicious intent and the means to synthesize the virus found that information, they could do a lot of harm. Just mentioning this, even though the information is already public, constitutes a second type of infohazard.

Attention hazards are information hazards that, even if the hazardous information is already technically known, pose a risk if someone draws attention to them. Here’s another example: even if information hazards are technically already known, someone that writes an article bringing attention to them might inspire someone that never thought to use infohazards for nefarious purposes.

The final type of information transfer mode I want to briefly mention is an idea hazard. These are very similar to data hazards, except they don’t actually require any specifics. Just the mere idea of something would be enough for someone to cause harm with it.

While considering large-scale infohazards can be interesting, it can also feel somewhat morally irresponsible, because a lot of them could be genuinely disastrous if realized. However, some infohazards with much smaller consequences can be a lot of fun to discuss; like Roko’s Basilisk, the worst case scenario of which is only eternal torture.

A knowledge hazard is a piece of knowledge that can cause harm specifically to its knower (like the classic, “I could tell you, but then I’d have to kill you” trope). Roko’s Basilisk is a knowledge hazard and now-famous thought experiment that goes something like this: sometime in the future, a superintelligent AI is built. It’s so powerful that it can simulate anything, and as a result, it can know everything that has happened and will happen based on its current inputs. Therefore, it can know everything you ever thought and did. It can also simulate life. Now, if you don’t devote the rest of your life to advocating for and assisting in the creation of Roko’s Basilisk, once it is created, it will simulate you and torture you for eternity.

While it’s an interesting concept, there are several problems with it practically. First, the technology is bordering on the edge of impossibility. Just because we aren’t there yet doesn’t mean it’s fully impossible though. Say the technology will one day be possible. There’s still not much merit to Roko’s Basilisk, simply because it doesn’t actually have an incentive to follow through on its torture. In order to be created, it’s in the basilisk’s favor if we’re scared into trying to build it, but once it is built, simulating us would simply be a waste of resources. It could still be built with human-programmed motivations, and that accounts for the problem of its incentive for torture; it would be pretty ridiculous for someone to build Roko’s Basilisk at that point, but if the technology is available, they might do it so that someone else doesn’t do it first. At that point though, it can all be solved with another thought experiment. If that technology is available, and is already being programmed with human intent anyway, why not just build a second basilisk that tortures anyone that builds Roko’s Basilisk? It completely disincentivizes creating Roko’s Basilisk, because the only reason to make it at all is to avoid being eternally tortured.

Roko’s Basilisk and convoluted solutions to it aside, some information hazards do pose some very real risks. As I was researching for this article, I found it difficult to find actual examples that I was comfortable writing about. That’s not to say that I came across heaps of destructive instruction, but there were some legitimate hazards that I wouldn’t want to disseminate. If you want a harmless one though, google the McCollough effect; it only lasts a few months.