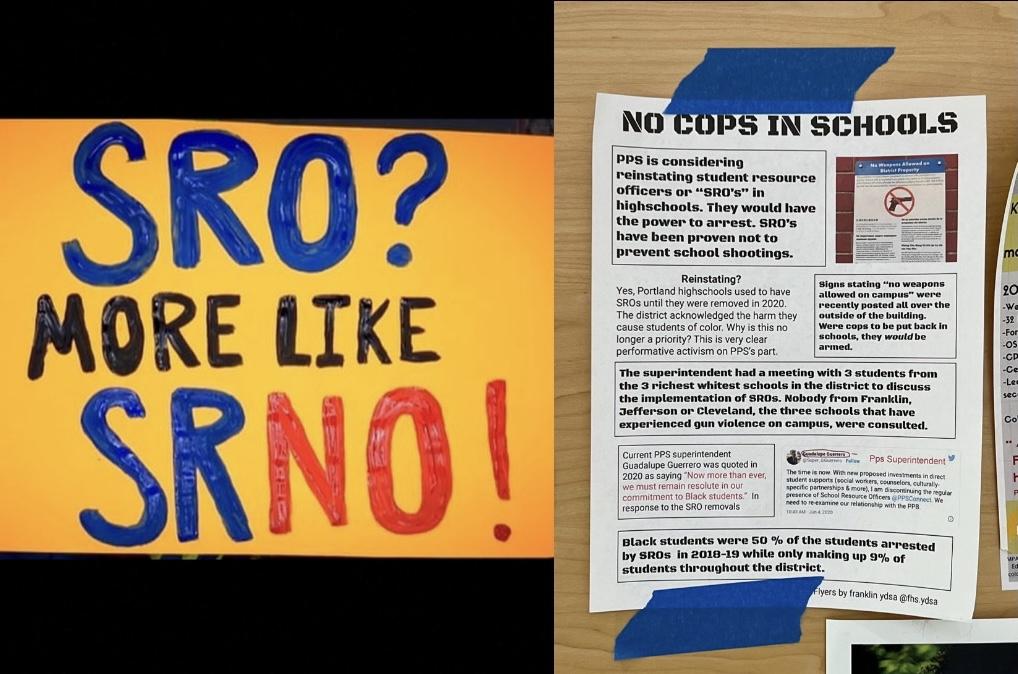

Left via NoSROsPDX Instagram, Right poster by Franklin’s Young Democratic Socialists of America

Littered across bulletin boards and school walls are flyers for clinics, apprenticeships, and information about climate change in the Pacific Islands. Yet, a nondescript poster on copy paper is the one that stands out. The title boldly reads, “NO COPS IN SCHOOLS.” Published by Franklin’s Young Democratic Socialists of America (YDSA), the poster illustrates a deepening divide in Portland Public Schools (PPS). Disagreement is present as PPS considers reimplementing School Resource Officers (SROs) to address school safety concerns, with community members from all sides of the debate expressing concern over the lack of information regarding a decision.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), SROs are “sworn law enforcement officers responsible for safety and crime prevention in schools.” Like regular police officers, they have the ability to make arrests and respond to calls, but the key difference is the additional roles they fill within school communities. They work in conjunction with school administrators to build relationships with youth, provide information about law enforcement careers, and develop safety strategies. The DOJ emphasizes that “while an SRO’s primary responsibility is law enforcement, whenever possible, SROs should strive to employ non-punitive techniques when interacting with students.” SROs are expected to use arrests as a last resort, keeping students out of the criminal justice system.

From 2001 to 2019 the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) managed an SRO program that shared these goals, with an SRO assigned to each of the nine PPS high schools. Officers were chosen based on their interest and passion for working with people, especially youth. According to Molly Romay, senior director of security and emergency management at PPS, interviews for the position were conducted using panels that included both students and staff. The officers received the same training as any other PPB officer, in addition to meeting training requirements from the Oregon School Resource Officers Association and the National School Resource Officers Association.

The training to become an SRO includes active shooter and restorative justice education. Trevor Tyler, former Franklin student and SRO, and current sergeant of the Child Abuse Team with the PPB, recalls training about topics related to youth like sex trafficking and social media, but adds that a lot of it was “inundated throughout all of our education as police officers” with a focus on “having an overall sensitivity to people’s experiences and where they’re coming from.” Franklin Principal Chris Frazier adds that, “SROs were trained through the lens of community policing which looks to first establish relationships with individuals within the community.”

The relationships he formed were Tyler’s favorite part of his work as an SRO and he states that “the school resource officer job didn’t get confined by the bounds of 8 a.m. to 3:30 p.m.,” emphasizing his “[vested] interest in the livelihood of these kids.” He lists bringing food boxes to students’ homes, taking them shopping through an official program, collaborating with school counselors, and informing students about law enforcement careers as a few examples.

Frazier highlights that “SROs were able to assist students and families regarding matters that were outside of the school’s purview,” like “filing a police report or answering questions about safety in the community.” SROs acted at the discretion of school administrators and, according to Frazier, “never worked independently or without the approval of the school admin[istration].” In 2016, Tyler received the Franklin Award, which Frazier calls “the most prestigious award given to a Staff Member, Student, or Partner.”

Despite the praise, Romay and Tyler both highlight that PPB’s SRO program was unique and that not all SRO programs are the same due to differences in training and hiring. Tyler also acknowledges that it’s hard to gather statistics around the effectiveness of SROs because “it’s like, do I know that the bad thing didn’t happen because I was there?” Although Tyler does recall taking guns off of students. The difficulty in establishing clear statistical proof about the effectiveness, or ineffectiveness, of SROs is mirrored in research.

A 2022 study by Brown University about schools who received funding for SRO programs through the DOJ found that while SRO presence appeared to reduce certain forms of violence within schools such as physical attacks without a weapon, it was associated with an increase in gun-related offenses, arrest of students, and school-based disciplinary measures like suspension. It is unclear whether this is due to “increased detection of student misconduct by SROs, or from increased pressure on school administrators to punish student misconduct, or some other mechanism.” As the authors write, “This reporting/recording phenomenon makes it difficult to ascertain with certainty whether SROs effectively make schools safer from the types of firearm crimes that SROs are often hired specifically to prevent,” highlighting the limitations of existing research.

The Brown study also reports that the increased discipline impacts Black, male, and disabled students more than it does for their White, female, or able-bodied counterparts. An SRO was found to more than double the increased expulsions for Black students compared to White students, adding 2.8 additional expulsions per 100 students, whereas the increase for White students was 0.80 additional expulsions per 100 students. Disabled students received 2.2 additional expulsions per 100 students.

Earlier studies corroborating this were a huge motive for the NoSROsPDX movement, a student-led group that protested against SROs within PPS. Their main goal was preventing the PPS Board of Education from voting in favor of an Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA) that would use PPS funding to formalize the relationship between PPS and PPB and increase SRO presence from four to five days a week, according to district documents, costing the district $1.2 million per year. PPB had cut the funding for the PPS SRO program, citing staffing and budgeting issues as the cause, prompting PPS and the city to reexamine the program. At the time, Student Representative to the Board of Education Nick Paesler, and Julie Esparza Brown, the only person of color on the Board, argued against the IGA, but Paesler’s vote was honorary and ultimately in 2018 the Board moved ahead with their decision. Then, in early 2019, Julia Brim-Edwards, who is still a member of the Board, proposed a resolution to suspend the agreement until more outreach could be done. Brim-Edwards’s proposal was approved. SROs were removed from PPS campuses in 2020.

The NoSROsPDX movement praised this decision and many saw it as a commitment to the district prioritizing the needs of students of color. Mayor Ted Wheeler tweeted in response, “Leaders must listen and respond to community. We must disrupt the patterns of racism and injustice.” However, Tyler thought “it was incredibly tragic, because that was an opportunity for us to be able to continue to build roads and bridges. And instead it was just kind of like we just closed off and isolated kids from having relationships with police officers.”

Now in 2023, after gun violence incidents have occurred outside of three PPS schools in the past year, PPB and PPS are considering reimplementing SROs. They’ve already added police presence to after-school events like athletics and school dances. Romay claims the officers are mostly former coaches or SROs.

The news about revisiting the idea of an SRO program broke in late 2022 during a press conference with PPB Chief Chuck Lovell. District communication has been limited, but Superintendent Guadalupe Guerrero stated during a Jan. 13 press conference that he was conducting focus groups about the topic.

So far, the student involvement has manifested as closed-door discussions with student representatives. One meeting featured representatives from Grant, Ida B. Wells, and Lincoln, none of the schools that experienced gun violence. Byronie McMahon, current Student Representative to the Board of Education, adds that “students from Cleveland and Jefferson also joined the superintendent for a meeting right after the Cleveland shooting.” The District Student Summit on March 10 provided an additional opportunity for high schoolers to supply feedback about school safety, although it had not taken place by this article’s deadline.

McMahon explains that “the task force just started so [the district] will be starting public outreach for that body soon,” specifying that it can be expected to begin somewhere in the next two weeks from March 6. The task force includes union partners, staff, violence prevention experts, and the school board.

A desire for more student involvement inspired Franklin’s YDSA to take action, pasting their “NO COPS IN SCHOOLS” posters all across the school. YDSA member Sophia Beffert explains that they created the posters in an effort to share information that was “kept under wraps by the district.” The posters highlight that Black students were 50 percent of the students arrested by SROs in 2018-19 despite only making up 9% of students throughout the district. In actuality, this refers to 2017-18 data from PPB, which reports that PPS SROs responded to 2,569 calls for service and arrested a total of 20 youth (not necessarily students) during school hours, of which 11 were Black. PPS enrollment data has African American students as 8.9 percent of the district population in 2018. Regarding the Brown University study, the PPB and PPS reports do not include statistics about disabled students.

YDSA’s posters bring to mind the ones created by the original NoSROsPDX movement, and the motivations remain the same: for the district to be transparent about their actions and to listen to student voices. Unfortunately, many students feel as though the district is failing. Beffert explains: “I think if the district … didn’t walk on tiptoes while talking to us for fear of legal repercussions, people would respond more positively to what they have to say.” She elaborates, “They either don’t tell us anything until the news does, or use such a rehearsed statement that most people tune out.” Some teachers echo this feeling, and in the days after the Franklin gun violence incident, two shared frustrations with students about the lack of communication, stating they received their information from the news.

Some community members are frustrated with the messages that are being shared. In the Jan. 13 press conference, Guerrero emphasized school safety as a shared responsibility and Romay repeated this sentiment. Yet some students disagree, explaining how the burden of safety makes them hyper vigilant and exhausted to go to school. Cooper Long, co-chair of Franklin’s YDSA, agrees that safety cannot fall on the shoulders of one person. He believes that “a large part of the mentality of having an SRO for safety in schools is the ‘good man with a gun’ idea that is so prominent in America. The idea that if a bad guy is out there, there will be a good guy to stop him.” However, he rejects this idea because “it’s built on individual heroism, heroism that may exist and should be applauded in individual instances, but should not be the foundation of keeping our communities safe.”

Community members are just as divided over the issue of SROs itself. Many students are opposed to inviting, as Beffert puts it, “a representation of state violence” into schools, citing concerns about police violence and racism. Beffert acknowledges that some students may feel safer, but ultimately wonders, “Are we sacrificing the emotional wellbeing of students of color for the emotional wellbeing of White students?”

Franklin Black Student Union member Jackson Roberson states, “I would not feel safer with cops in school just as I don’t with them in the streets.” Yet for others like Charlotte Storrs, a junior at Franklin, police presence isn’t something she’s entirely opposed to. At games it made her feel safer because she “enjoyed having the security of knowing that someone trained in handling violence and crime was [there].” However, she thinks “having police officers in school is very intimidating and somewhat unnecessary on a day-to-day basis.”

Angela Bonilla, the president of the Portland Association of Teachers (PAT), states, “We must make our schools a place where students feel safe and connected.” She continues, saying that the PAT believes “the solution to gun violence is not to harden our schools, but instead to soften them.” This can be done by “providing time and space for educators and students to connect and develop real, genuine relationships … [and] creating real restorative practices that hold our community members accountable and help them develop the problem-solving tools they need to survive in our world.” They are “vehemently opposed to deflecting public school funding for ineffective and harmful policing of our students,” according to Bonilla.

In contrast, Kristen Downs, a parent of PPS students, feels that removing SROs “was a political decision made without firm data to suggest that a police presence somehow made students, teachers and school buildings less safe.” Downs has created a petition calling for daily patrols of PPS campuses and the return of SROs. She writes on the petition’s change.org page that SROs are “urgently needed to ensure student, teacher, and staff safety.” Downs adds that the counselors and youth violence prevention managers since hired are necessary, but do not take the place of trained officers. The petition has amassed 676 signatures as of March 7. Downs did not respond to requests for comment.

Frazier sums up the community reaction well: “The perception of law enforcement has shifted in the U.S. and not everyone is comfortable with the presence of SROs, however many people also see that there is a specific and unique role that they play in our community.”

SROs are a potential response to part of a greater problem, and for Board member Andrew Scott, they’re “one potential component of the larger public safety question.” In the Jan. 13 press conference, he added, “I’m a little frustrated [that] the conversation in the community seems to become very binary, about, ‘Are you going to have School Resource Officers or not?’”

Advocates for the reimplementation of SROs are not hoping for an immediate reinstatement of the past program. Frazier states, “I am not advocating for the constant presence of an SRO in the building or on campus, [which] the previous model never required,” but explains that “having a relationship and immediate access to a resource officer was comforting in the event of an emergency,” and he enjoyed having “a thought partner in dealing with matters that might require police involvement.” However, he believes that if it were to be reimplemented, the program would need to be adjusted.

Romay agrees, asking, “What does it look like if we have had some dedicated officers just assigned to patrol around our campuses and not necessarily inside our buildings?” She believes that “we could reimagine something even better than an SRO program that still supports student safety as well as maintains a relationship with law enforcement.”

Tyler emphasizes the importance of this relationship and looks forward to “the day when there are opportunities to start that relationship back up in the classroom because [he] know[s] that [himself] and many others like [him] are waiting for that invitation to be able to start building relationships with students again.”

Tyler adds that “children are the most valuable thing in our society, and they deserve having somebody that’s going to advocate for them.” Hopefully, in discussions about SROs, students will be given the space to do so for themselves, even if many feel that PPS has not yet provided them with enough of an opportunity.

Overall, Frazier acknowledges that “the SRO conversation will never be one where everyone is satisfied.” However, he believes “that through education and time, trust can be established and may make people feel more comfortable, should this happen.” Tyler wants to see this occur through open conversations and states that “we need to double down on working to build these relationships. So that through that relationship, there can be that trust.”