Individual learning needs differ greatly from student to student, which can make the start of a new year bumpy without proper communication with your teachers. Every student follows their own learning journeys and faces obstacles like time management, as well as balancing other obligations such as familial duties or jobs, financial struggles, emotional rollercoasters, and social pressures. In a perfect world, public schools would have the funding and resources to adjust for all of these challenges. For some students, however, additional support in the classroom is necessary to even the playing field.

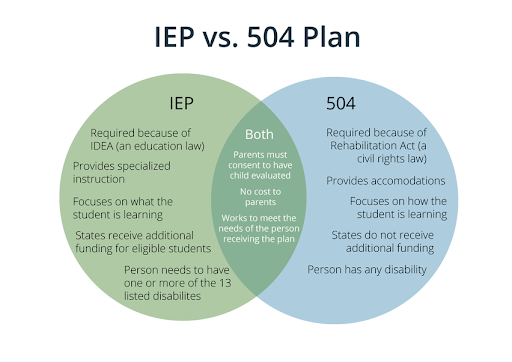

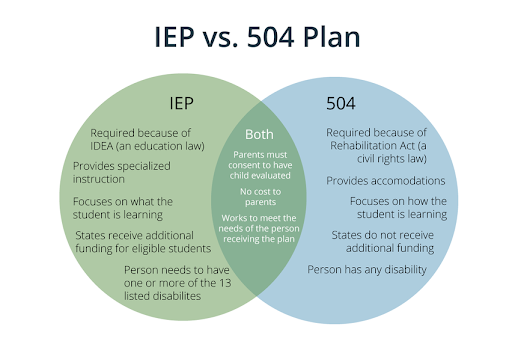

From Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, students with disabilities identified under the law (i.e. a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits day to day activities) are protected from discrimination and deserve the right to equal education. The idea is that with the protection of this law, schools can provide one of two options: a 504 plan, or an Individual Education Plan (IEP). Now let’s break this down.

The first things that may jump out at you are the use of “disability” and “impairment.” It is important to recognize first and foremost that this law protects a wide range of learners, who may all be in different situations: so, what is an “impairment”? Congress does not list the afflictions qualifying, as this would be far too long. Impairment itself is defined by the U.S. Department of Education, Section 504 as “any physiological disorder or condition, cosmetic disfigurement, or anatomical loss affecting one or more of the following body systems: neurological; musculoskeletal; special sense organs; respiratory, including speech organs; cardiovascular; reproductive; digestive; genito-urinary; hemic and lymphatic; skin; and endocrine; or any mental or psychological disorder, such as organic brain syndrome, emotional or mental illness, and specific learning disabilities.” The second caveat of qualifying for one of these plans is that it must significantly disrupt your abilities to learn.

I spoke with Julie Rierson, Franklin Vice Principal and the building coordinator for 504 plans at Franklin. Rierson is responsible for being a liaison between the case workers (counselors) for 504s and the district, as well as a point person for IEP/SPED services when district funding may be required. She told me that there are a few ways that a student may seek a 504 plan, but “[t]he more common route is where a student goes to a counselor and says, ‘I’ve been struggling with school the last year, my attendance has gone down. I’m having a hard time focusing.’” Or they have recently been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and, “they think that it would be helpful to have some accommodations. And so then, they would go through the eligibility process.” While this is common, Rierson explained that it does not always result in the granting of a plan. First, an eligibility committee meeting must take place. This meeting is made up of the student and their counselor, the family, a school psychologist (when necessary), and information collected from the student’s teachers. The committee prioritizes looking to other resources before automatically implementing a plan, some of which include tutoring support with SUN and in-class strategies. “The students have an opportunity to just talk about their experience,” Rierson said, describing the meeting. “And as a team, it’s decided whether or not we think the 504 plan makes sense.” After trying new strategies, “then a 504 may be considered. So we really try to work with the family and the student to determine what level of support is necessary and then implement that,” Rierson said.

Shala Santa Cruz Krigbaum is a senior at Franklin who is currently in the process of trying to obtain a 504 plan for ADHD. Although it may seem late to do this as a senior, the plans carry through post secondary schooling. Santa Cruz Krigbaum said, “Ever since school really started, I’ve been talking to my therapist about setting up a 504 plan.” Therapists or third party evaluators often work in communication with the school during this process. “[M]y counselor said that I wouldn’t necessarily be eligible because I have too high of a GPA for [a 504 plan]. And I had to elaborate that, hey, I have pretty severe ADHD, and I’m also trying to balance a job at the same time with school. So, if I weren’t to have a 504 plan, that might make my GPA lower.” Many students face this roadblock, and the reality is that unfortunately the later students look for these accommodations, the more likely they are to be overcompensating to achieve the grades they have.

An anonymous Franklin student said, “I found out I had dyslexia in eighth grade, and so my parents were like, ‘Oh, we should get [them] a 504 plan.’ We talked to the counselors at the middle school, but they made it really hard for me to get it because I had good grades and they just didn’t believe me.” With the legal qualifications being quite broad for 504 plans, schools look to the GPA for proof of struggling, but this number often does not reflect the weight that the student carries.

As Santa Cruz Krigbaum has gone through this process, she has some grievances: “[I]t just seems pretty ableist to me. It contributes to the stigma that only people with learning disabilities are failures, and the failures are the kind that need accommodation when, I think everyone with a disability needs accommodation regardless of their GPA because it doesn’t necessarily say how well you do. It’s how much you do in class, and all that effort you put in. It’s hard to quantify someone’s disability and how they function.”

Once acquired, the accommodations vary for each individual situation. Some students utilize their plan every day in every class, while others may have plans that focus on tests, and some additionally have specialized instruction if they have an IEP. Santa Cruz Krigbaum explains their ADHD: “[I]t affects every single part of my schooling, especially my schoolwork.” They continue to say, “I feel that I just have this expectation of myself to just do something right, and it can all just bottle up. I have regrets about how I go through school [almost] every single day.”

Brooke Porth, freshman at Endicott College in Massachusetts, got her 504 plan in preschool for a learning processing disorder. “I don’t process things as quickly as other people do. It can affect my speech, and the pace of class that is effective for me to learn. I have someone who takes notes for me so that I don’t miss things,” she says. For the most part, Porth says that her 504 has positively shaped her schooling. However, for Porth and many other students, it’s not quite as easy as it may sound, especially in public high schools. There is a shift that occurs after middle school, where students are expected to be responsible for their own education. While in many cases this “push from the nest” encourages growth, it can be more complicated for students who have accommodations. Porth attended John Stark Regional High School in New Hampshire where she was met with some frustrations: “Throughout high school, my 504 plan was not respected. I wasn’t getting the help I needed, and was denied accommodations surrounding testing. I had to go out of my way to tell teachers about my situation over and over when they were supposed to have a plan for me and accommodate me.”

Rierson shared that she and the counselors are working to calibrate the practice of granting accommodations. “We want to identify a much more clear process for it, because right now there’s six different counselors, and we just want to make sure that we’re approaching it the same way.” This will include resources for families wondering if a 504 might be helpful for their student, standardizing the resources to be easy to be easy to access and as equitable as possible.

With large class sizes, and the lingering stresses of the pandemic such as catching up on pandemic curriculum, the support given to students with 504 plans is often lacking. Theoretically, your 504 plan does all the talking for you, and students can focus on learning. However, as I heard from my interviewees, students often have to push to get what they need. Understandably, some students have difficulty discussing their needs out of fear that they are seen as shortcomings. Some worry starting the year off with conversations about accommodations could make them seem lazy or needy. The reality of explaining oneself is not mentioned when you get a 504 plan, and can come as a shock. This initial shock can feel isolating and frustrating at first. With time, and trial and error, these students learn resilience. Self-advocacy is an invaluable skill born from necessity: a habit Rierson made clear is very important to her within this process. So, how does one do it? Remind yourself that you are strong to have gotten this far. Remember that you see the world and learning in a unique way, and that is special and important. Now take a breath, and tell people what you need to succeed.

Fortunately, Porth provides hope for high schoolers. “In college I have the same accommodations. I take tests in my own room without distractions. I have a designated person to talk to when I need it. The college handles it very well.” Since colleges are paid institutions, this is somewhat understandable, but in any case, these accommodations, under either a 504 or IEP, are a legal right.

To my resilient friends fighting for unrecognized struggles, to those fearing judgment and jokes, to the teachers who want so badly to help and are doing their best, to students feeling frustrated with their own limitations, to friends not sure what to say or how to be supportive; these things take time. Your individual experience is important; keep trying.