My first exposure to the works of John Steinbeck came in sixth grade, when I read The Pearl, a wrenching novella that I found beautiful. Like so many others, his words struck a chord in me, and I asked my parents if they had any more of his books. They had quite a few.

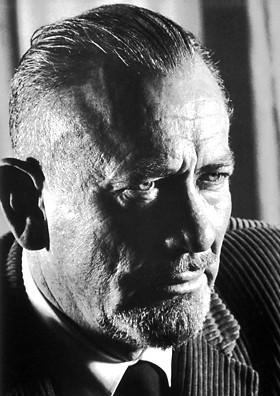

John Steinbeck, born in Salinas, California in 1902, published 27 major works throughout his lifetime. December 20 marked the 50th anniversary of his 1968 death from heart failure in New York City. He is buried in Salinas.

Today, more than 700,000 copies of Steinbeck’s works are sold per year worldwide. Steinbeck won a Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for The Grapes of Wrath, which sold 14 million copies in its first 75 years. He won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1962, and is widely recognized as one of the most influential American writers of all time.

Since The Pearl, I have read and reread the majority of Steinbeck’s works, and a number have gained personal significance to me. Many times I have turned to the idyllic scenes of Cannery Row for escape from worldly frustrations; I have mulled over that first description in Of Mice and Men, appreciating the paradise that too many of Steinbeck’s characters could not. The Grapes of Wrath taught me about America, East of Eden about myself. And the end of In Dubious Battle will always haunt me a little. In all of this, I am not alone.

Steinbeck’s works focus on America, and his best known stories take place during the Great Depression. Novels such as The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, and In Dubious Battle have “working man” protagonists, and emphasize the plight of poor Americans in the 1930s. Steinbeck often employs American mythology and archetypes in his cultural critiques of United States capitalism. Stanford American Literature professor Gavin Jones says, “I think he is seen as a very American writer, but I don’t think that he’s always upholding American myths and values necessarily—he’s always undermining them or looking at the contradictions in them.” Steinbeck’s outrage over the Great Depression largely prompted him to write The Grapes of Wrath (1939), a moving story of a family that travels West during the Dust Bowl, and a scathing critique of the American labor system: a refutation of the American Dream. “I want to put a tag of shame on the greedy bastards who are responsible for this,” quoth Steinbeck in his journal, while beginning to write the novel.

Steinbeck’s activist writing was met with negativity from some critics, and even the government. Steinbeck was allegedly audited repeatedly by the Internal Revenue Service, just to harass him. (Additionally, many of Steinbeck’s works are “banned books” in schools.) However, his work found mass appeal among the working class. Hundreds of thousands of copies of The Grapes of Wrath were sold in its first year, and it remains one of the most widely read pieces of American literature.

Gavin Jones is working on a book of essays about Steinbeck. Jones grew up in England, where despite his distinctly North American focus, Steinbeck was quite popular. “He has a kind of mystical effect on people,” said Jones, referring to Steinbeck’s worldwide appeal. “It’s difficult to put your finger on it…. A sort of humanism, and a democratic sensibility.”

In The Winter of Our Discontent, Steinbeck wrote, “No man really knows about other human beings. The best he can do is to suppose that they are like himself.” This sentiment of Steinbeck’s is what I most adore him for; he thinks, writes, and operates off of a basic understanding that everyone is ultimately equal. That is what makes his work so appealing to people around the world, and it is what gives him the power to instill his stories with such humanity, to convey such universal struggles and ideas. “He believes in kind of a collective unconsciousness and a sort of transcendent humanism,” says Jones.

Certain universal ideas are indeed present in much of his writing; paradise is one such motif. It is in the farm that George and Lennie dream about in Of Mice and Men, it is in Adam Trask’s initial vision of his marriage to Cathy in East of Eden, it is in a future for little Coyotito in The Pearl, and it is in the image of the little white house with peach trees that drives the Joad family west in The Grapes of Wrath. Of course, those dreams do not come to fruition; Lennie must die, Cathy shoots Adam, Coyotito is killed, and the Joads find only despair. But each in their own way, Steinbeck’s works acknowledge and play with that idea that everyone ultimately wants the same thing: happiness.

Perhaps it is for this reason—Steinbeck’s underlying assumption of equality—that working class America once comprised a large portion of his readership. White, poor, rural Americans are certainly the demographic that his work most directly represents. But Steinbeck believed in equality and saw—even studied—the struggle of all America’s poor. “He tried to enter into radically different perspectives from his own,” says Jones. Steinbeck often dealt with racial issues in his work, even if he was unsure how to address them. In Travels with Charley he famously investigated the issue of race in America, documenting his experiences and observations in the civil rights era South. “In Travels with Charley you have this sort of racial apocalypse at the end, and then a short final section… he kind of leaves it hanging there,” says Jones. “I don’t think he really resolves it.”

A staunch Democrat, Steinbeck supported desegregation and the civil rights movement. “I am sad for a time when one must know a man’s race before his work can be approved or disapproved,” he wrote in a letter. He was friends with Lyndon B. Johnson, who awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964. Steinbeck was considered a socialist, but was not officially a member of any socialist or communist party, and even criticized such movements in In Dubious Battle.

America has changed much since Steinbeck’s time. The Grapes of Wrath was once reviled by the Donald Trumps of the 1930’s; it was slandered, banned, burned. It is ironic that the political landscape has become such that the very group that book once represented so well should come to support the figure that it—that they—once so vehemently condemned: one so privileged and capitalistic, so amoral and demeaning, so bigoted and divisive. Steinbeck described the plight of the rural, white poor just as he did the plight of all people; such was his strength and beauty as a writer. But today, the commonality between all those that struggle, those that fight, those who dream like the Joads did—American dream—has been all but forgotten.

Just as the omnipresent allure of paradise, of happiness, emerges as a theme in Steinbeck’s work, so does that idea’s brother: the necessary pursuit of that happiness, equally embodied within the ideals of the United States and of humanity. Steinbeck’s characters are nearly always in a state of travel, pursuing their own ideal of happiness. “I think he liked road narratives because of his interest in these states of becoming, these states of emergence,” says Jones. And these states can be uncertain and difficult. It is difficult for Lennie and George, for the Joad family, for Kino, for Adam Trask. But they find comfort in their friends, their family, and their faith in the attainability of paradise—their refusal to believe that the world is what Steinbeck proves it to be.

Steinbeck’s ideal vision of America, with unity between all those who pursue happiness, is being slowly discarded. Trumpism has made a mockery of it; the working, struggling people of all races, sexes, and religions that Steinbeck fought for are so divided they can no longer unite. And in the country’s current transitory state (its political and ideological future uncertain), we find ourselves amidst our own vast road narrative, which spans from sea to shining sea. So it is important that those ideas from Steinbeck be remembered—the same ones that I began to read about when I first picked up The Pearl, the same ones that the Joads held so dear: unity, understanding, and most of all, the basic assumption of human equality.