Media representations of Portland have been executed in various ways. A city full of tofu-eating

vegans with solar panel roofs, or as the president described, a “Warzone.” Some depictions show the city as full of stereotypes, but Kelly Reichardt’s films offer a softer view. Despite being born in Miami, Florida, Reichardt tends to film in the Pacific Northwest, presenting Portland in a personal way and allowing the audience to recognize aspects of the city.

Ben Morgan, who is a long-time fan of Reichardt’s, moved frequently as a child but has lived in Portland for 11 years now. “There’s not really a place that I think of as my own except for this place that I chose as an adult,” he says. Morgan continues, “The way that she [Reichardt] captures that is just so enticing to me, the good and the bad of the city.”

Reichardt displays the humanity as well as the creativity that Portland offers. Libby Werbel, who has worked closely with Reichardt, says, “Portland’s a really great place for people to have autonomy and live full lives outside of celebrity hustle culture.” Werbel worked as Reichardt’s liaison to the Portland art scene during the filming of her eighth feature-length film, “Showing Up.” Reichardt wanted to use real artists’ work in the film, and Werbel helped bridge that gap. Werbel says, “It’s a whole other world. So, [she] needed somebody who spoke the same language.” The film portrays a young artist living in Portland and showcases the realism of navigating life, friendships, and a drive to create art.

Werbel says Reichardt was “really adamant that the actresses in the movie worked with each of the artists to really understand their practice and to be able to understand the physicality of making the art.” She explains that visual art in movies typically comes from a prop department, but Reichardt’s desire to use and credit real artists’ work was embraced by Portland, reflecting a more ethical approach to creating art.

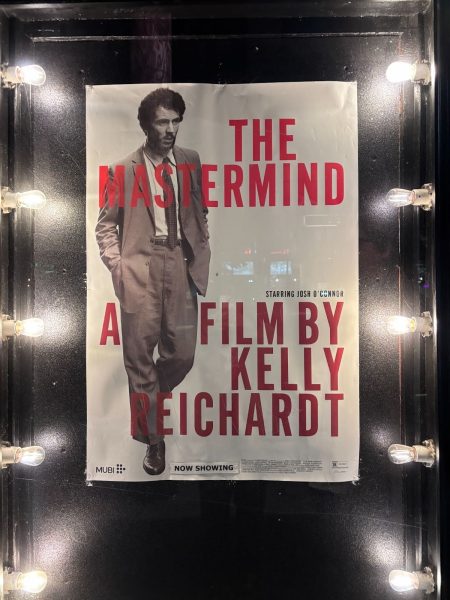

Set in 1970, Reichardt’s newest film, “The Mastermind,” which came out on Oct. 17, follows the story of an attempted art heist planned by the aptly named “Mastermind,” James Blaine Mooney, an unemployed carpenter. The audience’s faith in Mooney drives the movie’s suspense. Initially, the audience sees Mooney doing things that seem to be intelligent. He strategically hides the paintings, driving them out to his barn in the countryside to put them in the hayloft; however, the audience’s trust in Mooney’s capabilities diminishes as the film progresses. Shortly after hiding the artwork, he leads officers straight to it. We see his life fall apart and him struggling to maintain control. Newspaper articles in the film label him as being “at large,” a stark contrast to his situation, given the pathetic way that he is navigating his life. He ultimately gets hit over the head and arrested while protesting, possibly connecting to the large “No Kings” protests nationwide.

In the midst of all this, Mooney’s wife, Terri, stands outside their son’s bedroom door trying to convince him to go with her and his brother to stay with the grandparents. As Mooney’s life is crumbling, she remains calm and empathetic. Although sometimes overshadowed by his big plans and crimes, Terri represents how many women have shown up in their families’ lives in the background, often going unnoticed, but always holding things together while the men get the credit.

Morgan argues that the often male-dominated film industry can lack raw emotion and lean towards misogynistic narratives. Morgan says male filmmakers are “more often tying themselves to those tropes and intentions.” Far out of this field, Reichardt does not intentionally appeal to anyone in particular. She creates long, silent, and ambient scenes that convey so much with so little dialogue. This writing style results in nuanced and well-developed characters.

Morgan recounts a scene from one of his favorite Reichardt films, “Old Joy,” in which the two main characters sit in a hot spring together: “It is such a fascinating scene about their relationship and the lines that exist in friendship, the complexity of human relationships.” To Morgan, this sentiment feels particularly unique. “A lot of buddy comedy movies are misogyny-based or deal with sexuality in this very hookup, misogynistic way.” He continues, saying, “She’s interested in this other thing that’s going on.” Belittling women, he observes, is a sign of shallow male friendships portrayed in the media. Reichardt’s work quietly rejects these two-dimensional depictions. That rejection reflects her values as an artist.

“Everything is better when women lead,” says Werbel. Most people have been taught that men are natural leaders and that it is better when women stay out of those roles because they don’t have the skills. Reichardt’s work deeply challenges this narrative, with her gaining acclaim for her artistry. However, Werbel expresses she “just hope[s] for a day where [women’s identity] doesn’t have to be a part of how they talk about their creative process.” Reichardt’s independence from these large, capitalistic, and patriarchal Hollywood studios shows her commitment to authenticity and ethics. Her leadership values come from quiet empathy rather than dominance. Portland’s culture of independence and strong creative community closely mirrors the way she wishes to make art.

Empathy and genuine human connection are consistently represented in Reichardt’s work. Whether it’s the long, silent scenes, the displays of poverty, or the building of bonds between characters, she never fails to leave the audience with something. “She creates this silence, complexity, this empathy that I don’t think I’ve seen other filmmakers get to,” Morgan says. Even in “Mastermind,” a story about failure, Reichardt creates a reminder of the limitations of being human, allowing the audience to connect with the characters on an emotional level, and furthermore showcases how Reichardt’s work displays empathy and genuine human connections.