“I’m saying this as a Portlander, I’m saying this as a dad of two kids who I love biking around the city with,” says Dustin Buehler, special counsel to Oregon’s attorney general. “What’s unsettling to me is [that] I don’t believe the facts on the ground warrant these troops.”

Buehler is referring to the months-long dispute between Oregon and the Trump administration over the deployment of the National Guard to Portland to assist in protecting the city’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) building on S Macadam Ave., where protests have occurred almost daily over the past four months. Although there have been sporadic incidents of violence, the protests largely remain peaceful and manageable by the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) working with state and federal law enforcement entities. The Oregon Military Department, which is in charge of Oregon’s National Guard, declined to comment.

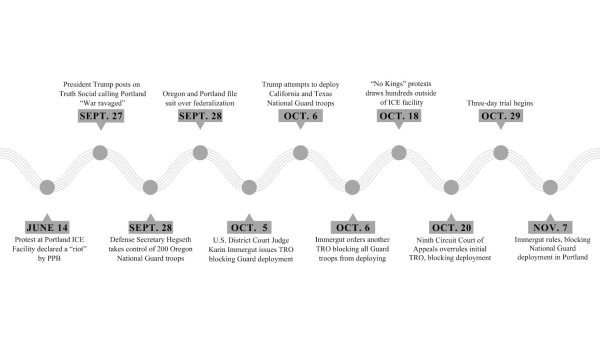

The level of protest was the critical piece disputed in the legal debates that ensued. The trial for State of Oregon v. Trump, which began on Oct. 29, set out to determine if the President’s move to deploy troops was made in a “good faith” assessment of the situation in Portland.

U.S. District Judge Karin Immergut ruled on Nov. 7 in favor of the state, blocking the deployment of any National Guard troops to Portland. “This Court arrives at the necessary conclusion that there was neither ‘a rebellion or danger of a rebellion’ nor was the President ‘unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States’ in Oregon when he ordered the federalization and deployment of the National Guard,” read her ruling. She cited the decrease in protest outside the ICE facility since the summer, and noted the minimal injuries reported by federal personnel.

Immergut’s ruling was hinged on the President’s assessment of the situation on the ground in Portland. Under Title 10 of the U.S. code, the President can federalize the National Guard if the federal government cannot carry out the law, or if there is a chance of invasion or rebellion. The court’s job was to decide whether Trump chose to send the National Guard to Portland in “good faith” under the parameters of Title 10, not whether the deployment was effective or the practices of the National Guard were legal.

The first call for deployment came from President Donald Trump’s Truth Social post on Sept. 27, where he described Portland as “War ravaged” and directed Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth to send troops to the city. The next day, Hegseth issued a memorandum that officially called 200 members of the Oregon National Guard into 60 days of federal service. The State of Oregon and the City of Portland were quick to respond, suing the administration to block the federalization.

“There is no national security threat in Portland,” said Oregon Governor Tina Kotek. “Our communities are safe and calm.” Portland Mayor Keith Wilson joined Kotek in responding, saying, “The president will not find lawlessness or violence here unless he plans to perpetrate it.”

Throughout the trial process, Immergut issued three temporary restraining orders (TRO) to delay the deployment until after the trial concluded. The first was issued on Oct. 4, blocking Oregon National Guard troops from deploying, and the second was issued just a day later, after the Trump administration attempted to circumvent the ruling by sending in California and Texas National Guard troops. The third TRO, issued on Nov. 2, extended the pause on deployment until her final ruling on Nov. 7, which fully blocked the federalization and deployment of the guard.

Earlier this year, in California’s deployment case, Newsom v. Trump, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the President, giving him and his administration the authority to federalize the National Guard in California. In their ruling, they reasoned that courts must give a “great level of deference” to the President’s determination that a condition exists to deploy the guard. Even when applying the Ninth Circuit’s standard, Immergut found that the President did not federalize the Oregon National Guard in good faith.

“The world is watching our city right now,” says Audrey Zunkel-deCoursey, president of the League of Women Voters (LWV) of Portland, which joined the Oregon and National branches of LWV in condemning the deployment. She highlights how the “peaceful, creative ways” Portlanders have been protesting, such as dancing in inflatable animal costumes, have attracted national coverage.

Each side painted a very different picture when characterizing the nature of the protests. The defense focused on incidents of criminal activity, including building damage and assault, and verbal abuse perpetrated by protestors. The plaintiffs honed in on the week leading up to the Sept. 28 federalization of the guard, noting that on five of the seven days before the federalization, the number of security personnel outnumbered the estimated amount of demonstrators, according to an Incident Command System 209 report authored by the Federal Protective Service (FPS). The FPS is a federal law enforcement agency who provides, among other services, security for federal buildings.

PPB Commander Franz Schoening explained in his testimony that despite a few exceptions, the protests throughout the summer and into the fall were low energy, and protest activity was declining until Sept. 28. He described these protests as manageable for PPB’s Central Precinct to police.

Following Hegseth’s memo, PPB anticipated that the deployment would cause an increase in protest activity outside the facility. The nights of Oct. 4 and Oct. 18 were significant for higher protestor turnout and energy, which was met with a “startling” response from the federal officers, testified Schoening. The use of crowd control munitions, including tear gas, affected protestors as well PPB officers, who had to leave the immediate area due to impact of tear gas and the assessment of the situation as unsafe.

The nightly protest gatherings were not always peaceful: conflicts between protestors and counterprotesters sometimes escalated into violence, and PPB made arrests, mostly on assault and property damage charges throughout the summer. FPS Commander W.T. — identified by his initials at trial — testified that despite occasional unlawful conduct like entering or blocking the facility’s driveway, many peaceful protests have occurred even at night, when the activity usually intensifies.

Schoening testified that local officers and federal officers have been at odds, especially after a PPB officer reported being hit by non-lethal munitions fired by federal officers on Oct. 18. Schoening explained that from the perspective of PPB, federal agents are using an excessive amount of force, to a degree that impedes local and state operations.

“You have to be very careful about the operations and choices you make. Crowd management is complex, and depending on how you show up and what you do can negatively affect the crowd,” testified PPB Assistant Chief Craig Dobson, who expressed his concern about the lack of training guard troops receive on how to approach and navigate crowds.

A point of contention discussed throughout the trial was protestors blocking the driveway up to the ICE facility. Oregon Sanctuary Promise and Sanctuary Promise Acts prohibit PPB from assisting with basic ICE protocol, like clearing the facility’s driveway, if those actions support immigration enforcement. The restrictions on PPB’s interactions with federal officers does not apply to communication for safety purposes; PPB and officials in the ICE facility kept a point of contact should any urgent situations arise, though PPB was not regularly contacted for assistance, testified the FPS Commander.

The defense used the frequent blocking of the facility’s driveway to contend that the current forces were unequipped to deal with the protests, arguing it was proof that the Title 10 deployment requirements were fulfilled. The plaintiffs disagreed, arguing that FPS had been successful in clearing the driveway, even without support of PPB.

High ranking FPS officials at the Portland ICE facility were allegedly not consulted before the Trump administration decided to federalize the guard. FPS Deputy Regional Director R.C. — who was identified by his initials at trial — testified that he knew nothing about the deployment until it was announced, saying on the stand his first reaction was, “What would I do with 200 guardsmen?”

The defense also relied heavily on incidents in June, when the ICE facility was shut down from June 13 to July 7, due to building damage sustained during protests. “It was too dangerous for my people to go to work at their desks,” testified ICE Field Director Cammilla Wamsley, who is in charge of ICE offices in Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. While repairs were made, operations moved to another location that could facilitate administrative functions, and arrests of protesters were made in both months.

Immergut’s ruling places a clear limit on federal power, setting a national precedent. Similar cases are being litigated in California, Illinois, and Washington, D.C., and the Trump administration has already alluded to further deployments in other U.S. cities around the country, including New York, Baltimore, and San Francisco. “This trial that we just had … is the first time that question has ever gone to trial in the United States,” says Buehler. “What happens in Oregon is going to be really, really important for other cities that are looking at this.”