Finland’s education system has been described as a student’s dream. The perks include shorter school days and minimal homework, no standardized testing before age 16, and the best part, a required 15 minutes of play for every hour of instruction. All of these unconventional methods consistently produce some of the highest global test scores and the title of most literate nation. Now, Finland is pushing the boundary of education further with the introduction of a new standard: project-based learning.

According to the Buck Institute for Education, project-based learning (PBL) is defined as a teaching method in which students work for an extended period of time to investigate a generally current and complex event. Advocates of PBL argue that this teaching style encourages holistic and intercultural understanding by first having students learn the subject matter and then boosting that knowledge through direct application. In addition, through incorporating the use of technology and other sources outside the school, it creates a more interactive and exciting learning environment that prepares students for the 21st century. An example of this innovative learning style occurred last year when students in Hauho, Finland tackled the subject of immigration. The topic was incorporated into classes studying German and religion, as students carried out street surveys to garner local opinions about immigration, as well as visited a nearby immigration center to interview asylum seekers. They later shared their findings via video-link with a school in Germany that had carried out a similar project. This assignment illustrates the applicable style Finland is striving to integrate into their curriculum.

Chris Frazier, one of three vice principals at Franklin, explains that PBL is not singularly Finnish. “The Makerspace is a way in which schools are trying to incorporate project-based learning.” He describes the importance of getting students to do things hands on and look at the content of what they’re learning differently. When asked if it would be possible to include more project-based learning in schools throughout the United States, he points out the difficulty of changing such a well-established field across a very large nation. “Each state’s education system is run a little differently, so it’s not as succinct as Finland.”

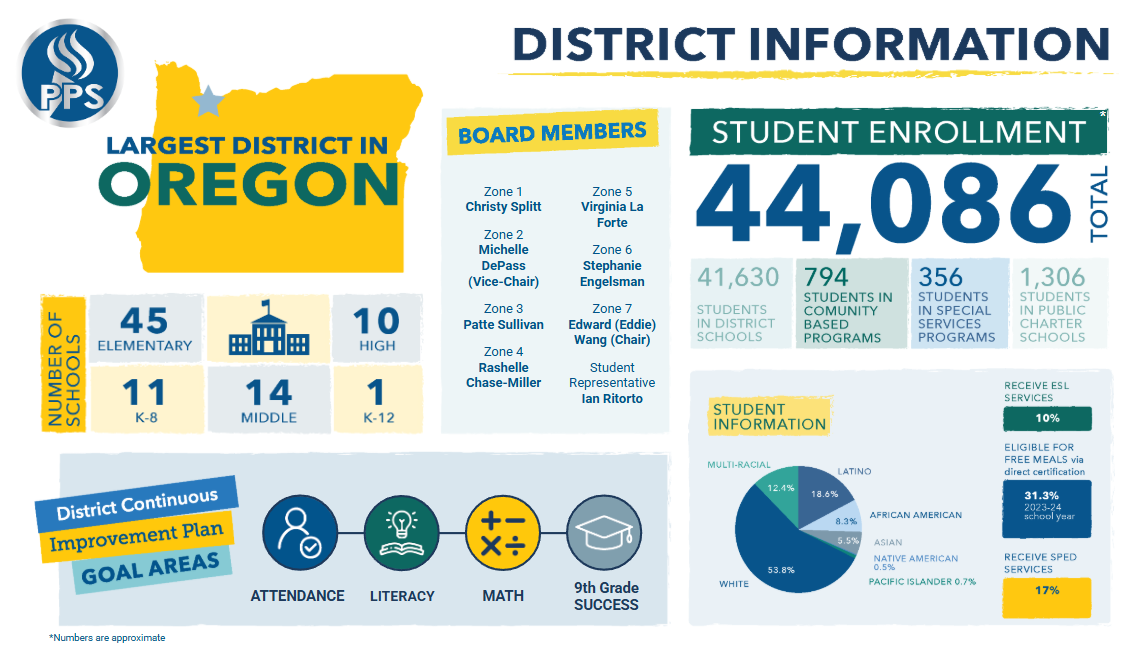

However, Frazier states that one possible aspect that hinders the success of education in the US is that teachers are “overworked and underpaid.” In Finland, teachers are highly valued, well-paid, and the field itself is extremely competitive. In addition, teachers are required to obtain a master’s degree. In most Finnish schools, teachers spend four hours a day in classroom and two hours every week on professional development. While only able to speak for Portland Public Schools, Frazier explains, “As you look at the amount of time that is devoted for teachers to work on their professional development, it pales in comparison.”

With a system as successful and effective as the one we see in Finland, it is important to understand the reasons why Finland is able to adopt such an experimental education system. Comparatively, Finland has a very small economy, low poverty rate, and a very homogeneous population. While these factors make it difficult for the United States to use Finland as a realistic education model, increasing the relevance of subject material and putting a greater value on our teachers could strengthen our educational global ranking. Says Frazier, “Giving teachers the wages they earn, providing them with professional development and also holding them accountable to certain standards will definitely move the dial in the direction we would want for our educational system.”