El Niño’s impacts on weather patterns are predicted to last until at least April, causing people across the Pacific Northwest to experience generally warmer conditions. El Niño is a naturally occurring weather pattern that correlates with warming surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific. It occurs every two to seven years, causing weather changes throughout the United States (U.S.) and beyond.

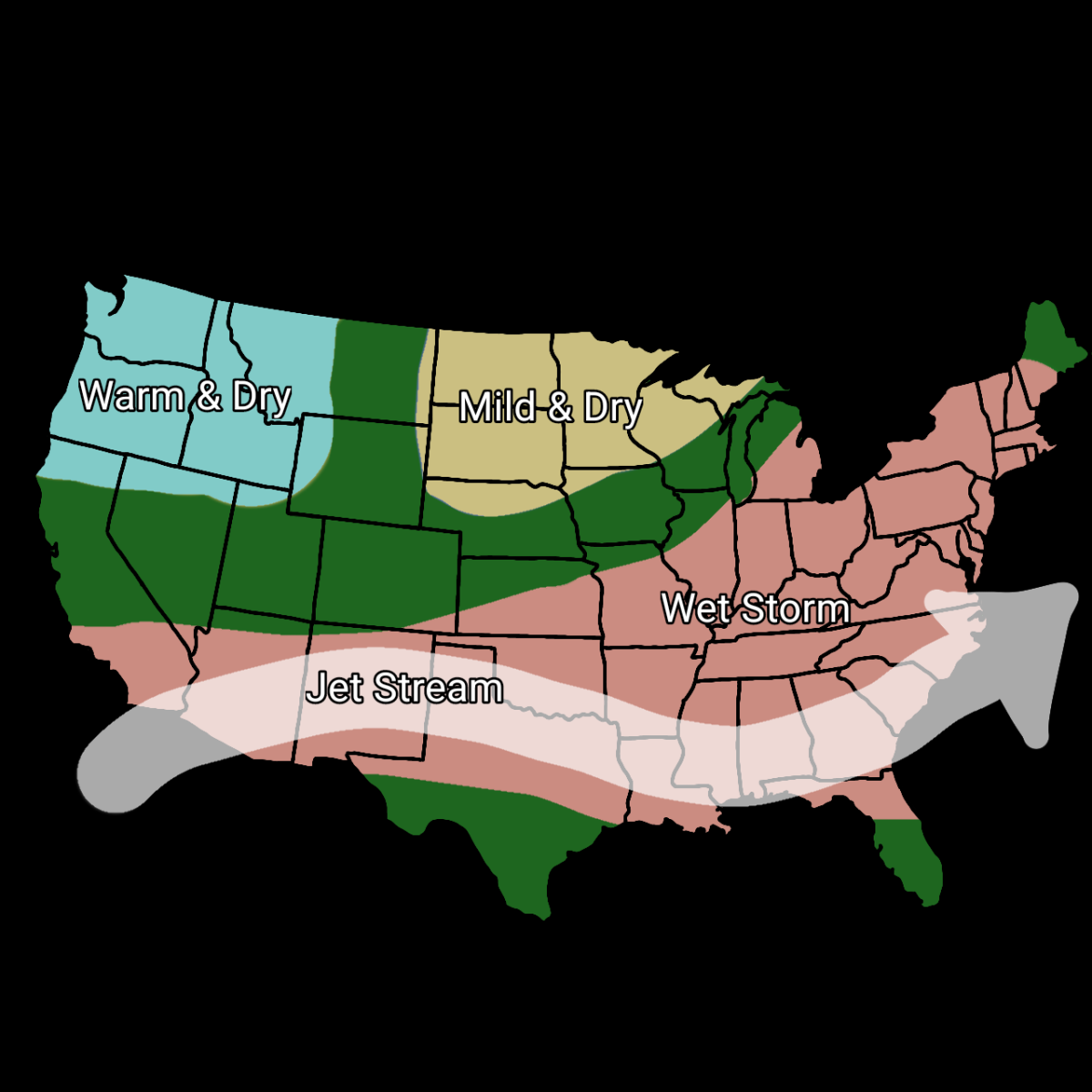

In regular conditions, trade winds in the Pacific Ocean blow west along the equator, moving warm water from South America toward Asia. Trade winds follow a permanent pattern blowing from east to west and are located both north and south of the equator. El Niño breaks this cycle, making up one part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Cycle. Alongside this is La Niña, which causes the opposite conditions. During El Niño, the normal westward trade winds that blow along the equator weaken, moving warm surface water eastward from the western Pacific to the coast of northern South America. In the U.S., increased ocean and atmospheric temperatures strengthen the Pacific jet stream and move it further south. An El Niño year is classified by “the water temperature [being around] 0.5 degrees higher [than average] for three months in a row,” says Megan Whisnand, the AP Environmental Science teacher at Franklin.

Instead of determining the day-to-day forecast, El Niño predicts general weather trends for the seasons. For example, despite the week-long ice storm that unfolded over much of southwest Washington and western Oregon in early January, overall, the Pacific Northwest experienced a very mild winter. “The Pacific Northwest saw temperatures much above normal in December 2023, with Portland recording its second warmest December on record,” remarks Daniel Hartsock, a meteorologist at Portland’s National Weather Service Office. Typically, El Niño does cause warmer conditions, however, Portland’s high temperatures being above average for 23 days is out of the ordinary.

In this particular case, El Niño developed between June and August 2023, reached moderate strength by September 2023, and peaked with its most extreme effects between November 2023 and January 2024. The impacts of El Niño have the potential to continue for up to a year after its development, meaning it could continue to influence weather throughout 2024.

During the summer months, El Niño is generally far weaker than it is in fall through spring, with the most intense effects occurring during the winter. This typically results in warmer and drier winter conditions, but, according to Hartsock, “There is not a strong signal during El Niño for the Pacific Northwest when it comes to precipitation.” Although precipitation is usually below average during El Niño winters, multiple atmospheric rivers pushed Portland’s rainfall above average, with 18.80 inches falling between December 1 and February 9, well beyond the usual 12 inches.

One impact of El Niño is a lack of snow in the Cascades, as warmer temperatures and high-elevation rain quickly melts snow above 5,000 feet. Hartsock notes that despite “cooler temperatures across the Cascades allowing for increased snowfall in January,” snowpack remained low. “As of Feb. 10 the current Snow Water Equivalent remains below normal — around 80-90% below normal in Oregon and 50-70% below normal in Washington,” says Hartsock. This resulted in less abundant snow in ski resorts and pushed back the start of ski season.

The ENSO Cycle occurs naturally, switching between El Niño and La Niña every two to seven years, with El Niño happening more frequently. The most recent occurrence of La Niña started in the fall of 2020, and the previous El Niño started in 2016. For the current cycle, “there is an 80% chance that El Niño ends and transitions to ENSO-neutral sometime this spring, between April and June,” says Hartsock.

Recently, temperatures have been above average compared to previous years, mainly due to climate change. Hartsock notes, “The interaction between climate change and El Niño is not completely understood, but El Niño could temporarily exacerbate the warming effects of climate change” through its weather patterns. It exists in the context of climate change, where human activities result in an increasing concentration of greenhouse gasses trapped in the atmosphere, causing warmer temperatures. 2023 was the warmest year on record, and 2024 may be even warmer. Still, it is important to remember that El Niño does not dictate everyday weather, and is only one factor that determines overall trends.

When teaching about El Niño and weather, Whisnand hopes to deepen students’ understanding of related topics, and, in doing so, increase their awareness. “These weather patterns tie into other things that we’ve learned about like biomes and why certain habitats are where they are,” says Whisnand. “I want [students] to think about where they live, what they know, what they’ve experienced, and how that plays into the big picture.” It helps situate students’ lives in the context of the world around them and the processes that exist.

El Niño isn’t very well-known or discussed in the general public, as most people use weather apps to gain insight into a particular day’s weather, rather than following the general trends. However, it is fairly common knowledge that this has been a mostly mild winter in Oregon. “I don’t think people really pay that much attention,” but “I personally think it’s good to be more aware of how the world works and the ramifications of that,” says Whisnand. Approaching inevitable weather events — such as El Niño — with curiosity can foster a greater sense and acknowledgment of the world, putting current events into perspective.