Two Portland Public Schools (PPS) have been closed since Jan. 15, 2023, when inclement weather conditions forced all PPS schools to suspend instruction. Robert Gray Middle School and Markham Elementary School sustained severe damages, leading to their extended closure and the displacement of over 1000 students.

As a result of the catastrophic ice storm, Portlanders across the city found themselves amidst the chaos of infrastructure not built to withstand increasingly intense weather patterns. Downed trees tore through power lines, flattened cars, and fell through roofs; within homes, families piled on blankets and dug out candles to combat freezing temperatures and failing electricity. Now, over a month later, PPS communities continue to feel the impacts of the storm as a result of the building damages.

Kirsten Carr, a parent and the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) vice president from Robert Gray, explained that transportation has been a big change for her kid as a result of the closures. Students from Robert Gray were rerouted to Jackson Elementary School, where the two schools now share the same space. This means that normal transportation routes have adapted to accommodate students who need rides to various schools.

Students from Markham were sent to four different locations. Kindergarteners, the Intensive Skills Classroom, and one second-grade class are at Maplewood Elementary School. First and second graders are at Hayhurst Elementary School, and one second-grade class plus all of the third graders are at Capitol Hill Elementary School. The fourth and fifth graders are at Rieke Elementary School.

Jackson Middle School has become a transportation hub: Buses pick up Robert Gray students and take them to Jackson; meanwhile shuttle buses pick up Markham students from Jackson and take them to the four different locations. Many students have to first walk to Robert Gray and Markham, as they did when still at their regular schools, but now have to take a bus in addition to their regular commute. For Carr’s sixth grader who has been rerouted to Jackson, the adjustment has meant getting home later than he is used to, with less time between extracurricular activities and school.

On Feb. 13, parents of both schools were informed that their buildings will remain closed until at least the fall. At Jackson, makeshift partitions and standing whiteboards separate a common area open-air plan into multiple “classroom” spaces referred to as pods. The conflicting bell schedules mean students are constantly moving about and are in close proximity, despite the lack of a noise barrier.

Naturally, the two schools have had challenges navigating and sharing a space meant for far fewer students: “It’s a distraction both visually and auditorily,” said Lisa Newlyn, the principal of Robert Gray. Even though classrooms are crowded, many have found ways to accept or find silver linings under uncomfortable circumstances. Jackson and Robert Gray will both feed into Ida B. Wells High School, and current students are getting exposure and time to socialize with students they may see again soon.

Although the situation is somewhat chaotic, a lot of thought and advocacy resulted in the choices made, even though it will be unsustainable in the long run. When developing plans to support students, principals juggle numerous factors and identify the needs of their communities. Traniece Brown-Warrens, the principal of Markham Elementary, compared a school community to an entire ecosystem, which moves and is impacted by many things. When trying to decide where to send students, safety, transportation, nutrition, social and emotional health, and the financial needs of the community are considered; as a result, ideal solutions are elusive. While debating between virtual and in-person options, she took note of the financial and emotional strain online school would entail for families. The community would have to figure out new childcare plans for their elementary-age students during the day if virtual learning was put in place, so Brown-Warrens made it a priority to avoid that outcome.

Parents’ opposition to online learning was widespread for many reasons; other concerns ranged from missed content to the lack of social emotional learning. “It’s not good for the kids,” said Jennifer Crow, a parent from Markham. “It’s one thing when everybody was in that position, but it’s very different when it’s only one school.” She worried about the learning differential between online and in-person school, and along with numerous other parents, chose to do something about it. They sent emails to the school board, to the district, and to local representatives, asking for answers and updates. A resulting meeting was scheduled by a local representative, who called a public meeting and invited PPS staff to address family concerns about the situation.

Carr expressed frustration at the lack of transparent communication by the district after the closures. Her annoyance was echoed by other parents, who also felt that relevant information about the timeline for building repairs and reopening, was insufficient. Even plans for making up instructional time felt disingenuous to parents. As of the time of publication, the district did not have anyone available for comment.

“Students and parents have opinions about things that are valid and should be taken into consideration,” said Carr. “We’re all stakeholders in this public school system.” She explained that the district and parents have to work together to problem solve and hopes that communication can take a positive turn moving forward. Carr wants to see the impacted families and students treated as the invested stakeholders they are “and not just people that need to be rescued.” Situations such as these result in a lot of blame, but she hopes clear communication would help shift the conversation towards adapting to changes rather than the frustration of back and forth conflicts. Carr also hopes to see the development of a comprehensive emergency plan, so that other schools won’t face the same challenges if something similar were to happen again. Separately, Crow also mentioned a desire to see a comprehensive emergency plan in the case of a damaged building, for the benefit of any future schools dealing with emergencies.

Newlyn explained that educators have been hyper aware of the fact that soon middle school students will be moving on to high school and attending Ida B. Wells as freshmen, especially in context of the disruptions.

A current concern from educators is that students will be ill-equipped for their futures as a result of learning disruptions like the pandemic and the snow closures. “We’re all wondering: What do kids need to learn and how do they get the instructional minutes that they need in order to move forward and be successful this year, so that they’re ready for their next age and grade?” Newlyn hopes that school can still provide them with necessary communication and social skills in addition to the curriculum standards, so that they can go on to become mature young adults. “This has the opportunity to be something that they can learn from as we all grapple with this really big problem that they are [at] the center of,” said Newlyn.

Newlyn explained that it’s easy to look at the polarization and discourse that impacts national media and politics, and worry about similar division in local spaces. She is excited by moments of conversation and hearing students’ voices, such as student speeches shared at a board meeting concerning course changes that would impact them. For the closures, this means putting student needs at the center of the conversation. Newlyn hopes students will come out of this catastrophe having witnessed an example of mature problem solving. Brown-Warrens echoed these sentiments, explaining that even at the elementary-school level, they are already working to instill critical thinking skills and composure during problem solving in order to prepare students for next steps.

But the shift is more than just a distraction to learning. “To be displaced is a loss of identity,” shared Newlyn. “We don’t have the things that we find comfortable, that make us Robert Gray.” Clubs, regular activities and the inner workings of the community have, if not ground to a halt, been changed by these closures. “The kids do miss us being in our atmosphere,” shared Brown-Warrens. Every week in Markham’s cafeteria, students participated in an event they called “Fresh Friday,” where they got a chance to show off their “fresh talent.” Now, students ask her questions about when they will return to these routines.

“It has been really enlightening to see the differences between what has mattered and bothered the teachers and staff and what has mattered and bothered my kids,” said Brown-Warrens. Kids are experiencing both the discomfort and loss that comes with a location change, but also the excitement of being somewhere new. Many students are simply excited by the new playgrounds, which are often upgrades from the ones at their regular schools. That being said, the absence of community elements is certainly noticed by students. “I had a kinder[gartener] ask me: ‘What happened to Mr. Owl?’” Mr. Owl is the custodian of Markham Elementary School, and students were curious about his whereabouts and wellbeing.

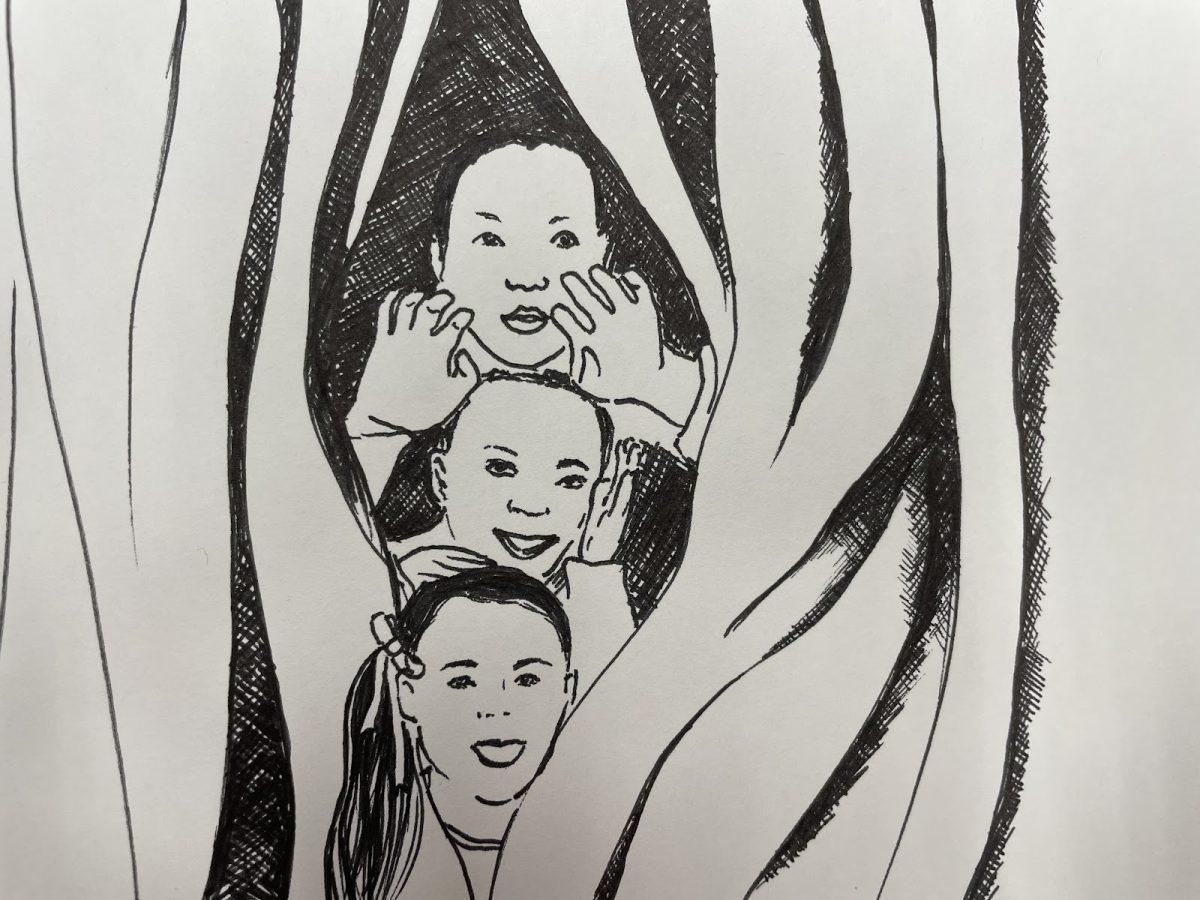

Brown-Warrens has done her best to address concerns and be there for students, even when bouncing between locations. Recently she moved from school to school on a “love tour,” bearing heart puppets full of the questions and anxieties students had expressed. She addressed concerns about school traditions such as the end-of-year field trip for fifth graders and the yearbook.

Parents agree that community efforts to serve students despite the challenges have been consistent throughout the disruptions. Carr emphasized her appreciation for how engaged the local school community has been when responding to changes, with dedicated custodians, staff and administrators, and parents eager to help.

The snow closures have “enlightened what kids today need,” said Brown-Warrens. In this day and age, social and emotional learning alongside current technology are crucial components of an education that adequately prepares students for their futures; although the systems, buildings, and standards currently in place are often designed for or impacted by elements of older education models. “I see [the closures] as an opportunity to reimagine what education should look like for kids that are actually going through the educational system today,” said Brown-Warrens.