The hallways are bustling as winter chaos ensues. Students attempt to scribble out answers to months-old assignments, winter sports are in full swing, Franklin Film School gears up for its annual student screening, and class presidents prepare their campaigns for re-election. Just two months ago, however, these halls were empty, occupied only by the seemingly permanent smell of Franklin’s famous nachos.

For 26 days, teachers hit the picket lines, parents found last-minute childcare, and students watched with bated breath as the disagreements between the teachers union and the district unfolded.

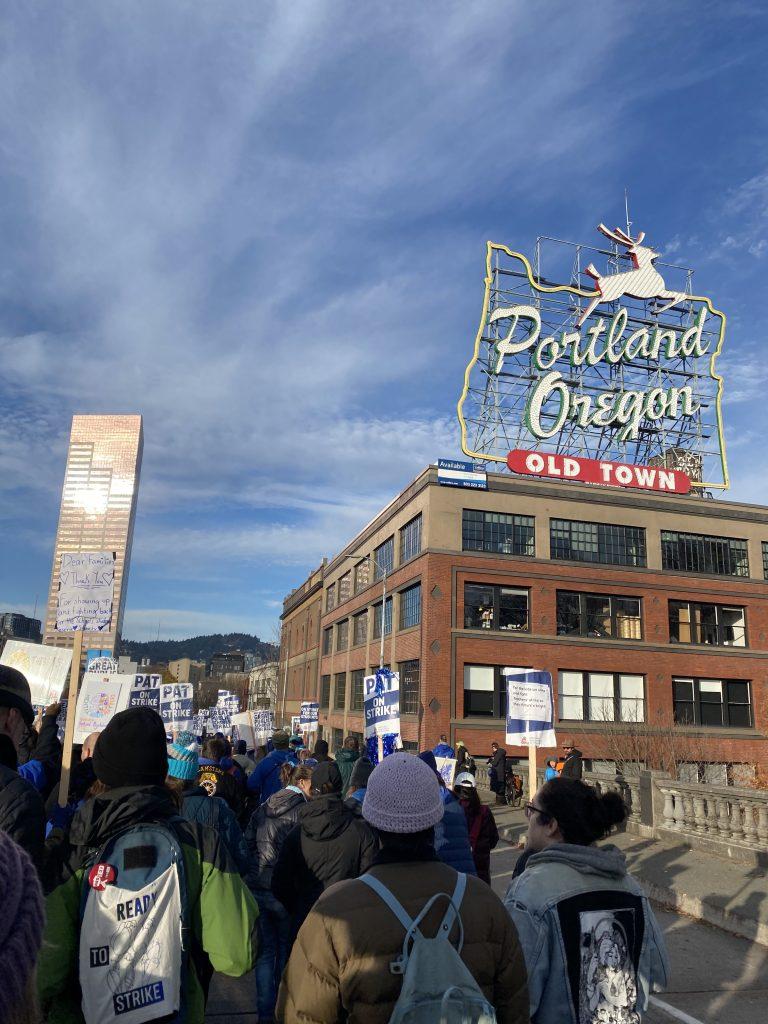

Portland Public Schools (PPS) and the Portland Association of Teachers (PAT) began negotiating a three-year contract in Oct. 2022, before transitioning into state-led mediation at the end of Aug. 2023. On Nov. 1, 2023, their inability to reach an agreement climaxed in the form of a strike that spanned 11 instructional days. During this time, teachers and community members formed daily pickets at schools and larger protests in more central locations; PPS headquarters; PPS staff’s neighborhoods; and, on one occasion, across a bridge. A tentative agreement was finally reached on Nov. 26, 2023; subsequently, community members were informed school would be restarting the following morning.

Both the PPS Board of Education and the PAT voted to ratify the tentative agreement on Nov. 28, and, as part of this agreement, the school schedule was rearranged to compensate for lost instructional days. Dec. 18-22, Jan. 26, Feb. 19, April 8, and June 12-14 were added back to the school calendar.

The full tentative agreement is a 123 page document, but some of the most notable agreements include: a three-year 13.8% cumulative cost of living increase, replacing mandatory minimum student suspensions with trauma-informed support, and the addition of class size committees to help resolve class size disputes. Over a month later, discussions are dwindling and focus is shifting, but the PPS community is left with the question of how to move forward.

Moving forward began on Nov. 27, 2023, when Portland students returned to classrooms. Despite a two-hour late start, the return was reminiscent of an average day at Franklin. Administration worked to make the transition as seamless as possible after weeks of working alone in the building. “A school is not a school without students and teachers,” says Franklin Principal, Dr. Zulema Naegele.

Jennie Camber, a Glencoe Elementary School parent, recalls, “The strike was reminiscent of the COVID shutdown with a lot of anxiety and uncertainty — every day my kids would ask if they could go back to school, and we’d have to tell them no, not yet.” Although her children are now back in class, concerns linger around what she describes as “learning loss.”

Franklin students have become accustomed to educational uncertainty, and have learned to utilize time off to their benefit. While some spent their time doing needed catch-up or staying on top of preparation for upcoming Advanced Placement (AP) exams, others marched alongside their teachers. PAT Student Leader and Franklin student, Callaway Calypso Kupper, recalls, “It was fulfilling to be involved in collective action … and seemingly make a concrete difference in our community.” Many seniors slogged out supplemental essays for college applications. However, the strike did not make the application process any easier. Some seniors applying early decision didn’t receive the required application materials in time. Without official transcripts, counselor and teacher recommendation letters, and much-needed application support, some students were left to personally reach out to admission teams and inform them that portions of their application would be late. Josephine Emanuel-Mitchell, a senior applying as a musical theater major, had earlier application deadlines due to also having to do in-person auditions. She describes that while she was promised support during the strike, that promise wasn’t fulfilled. “It was difficult for this to be ‘for the students’ but there was no support for the students.” Emanuel-Mitchell continues, “I had to do so much work just to be where every other student in every other district was.”

Students in theater, athletics, and our very own Franklin Post tried their best to adapt to extracurricular life without the support of educators. The boys cross country team met to run at 3:30 p.m. every day in preparation for state championships. Lenore Myers, the director of marketing and distribution for the Post, distributed paper copies of our third issue on the picket lines. Meanwhile, the cast of “The Little Mermaid” performed “Under the Sea” at Franklin’s morning picket line.

All extracurricular activities took a hit without educator leadership. The aftershock of this interruption is still felt school-wide, but it hasn’t stopped Franklin students from achieving some impressive feats upon their return. Just days after their return, the cast of “The Little Mermaid” put on a remarkable six-show run. After winning state, the varsity boys cross country team placed 14th at nationals. Brennan McEwen, a junior on the team, highlights that, “[the strike was] a big benefit before the big championship season meets as we [were able to get] a lot more sleep.”

The gap in instructional time delayed curricular schedules, which presented many difficulties, especially for AP classes that have set exam dates. Sahnzi Moyers, an AP Biology teacher, says, “I was very concerned as the threat of a strike kept becoming more and more real. … I knew that I had to be proactive … I posted the materials for our next unit on Canvas before the strike began. … [after the strike] we had to kind of rush our way through the unit to get back on track with our timeline, [so] I allowed students to use their notes during the unit test.”

The decision to remove half of winter break to make up instructional time was, as could be expected, very controversial among students. The night of the contract’s ratification, students from around the district came together to present alternate makeup days to the board. Regardless, the tentative agreement — which outlined the contracted makeup days — had already been passed, leaving no room for student input.

On Friday, Dec. 22, it was reported that only 500 students were present — far off from Franklin’s population of nearly 2000. The attendance rates led people to question how effective the added week actually was. Scott Barrentine, a science teacher at Franklin, states, “The lower attendance rate made it difficult to keep moving at pace, but it also was an opportunity to catch up students who had been a little further behind.” PPS’ Board of Education Chair, Gary Hollands, says, “Regardless of which way we went with makeup days … the [kids] weren’t going to get the educational value we would like for them.”

In response to large absences, some teachers simply stated they would not be teaching any additional content during the added winter break makeup week. Moyers said that AP Biology students were expected to work through winter break already, so the added week didn’t have a major impact. However, classes like AP U.S. History had to cram units’ worth of content into a few short weeks, including the makeup week. AP U.S. History teachers often strive to have former President Abraham Lincoln dead by winter break — to ensure that students are on track for the AP test in May — a checkpoint Franklin students ended up meeting.

Divisions over the makeup days demonstrate the leftover tensions from the strike period. People attacked communication strategies from both sides, viewing them as inflammatory and inaccurate. Misinformation spread, and often the union and the district pushed opposing narratives.

Tensions peaked when board members’ properties were vandalized by unidentified perpetrators. Hollands, one of the board members who experienced this, states, “The vandalism seemed like an adult issue, not necessarily something that was done for the best interest of our kids.” Julia Brim-Edwards, the other board member who experienced vandalism, spoke about the topic at a post-strike board meeting, saying, “I know that those actions that happened the last couple of weeks are not representative of Portland teachers.” Many were upset that the vandalism overshadowed the crux of the issue and made the entirety of the union look bad, and, for the first time since before the strike, teachers stood in solidarity with the board.

Camber returns to the idea of the opposing narratives, explaining, “It felt like the rhetoric was very divisive; there was very little room for questions and analysis and everything was black and white. I felt like if I questioned anything around the PAT strategy, or brought up the potential future budget cuts the district would be facing, I would be labeled as a teacher-hater or anti-union.” Making room for more nuanced conversations starts with expanding education on the topics being bargained on. Financials were a key point of contention as gaps in proposal costs and state funding numbers differed, and Hollands states, “I wish that more financial education was done, so people can really understand the financial ramifications of what the asks were.”

This question of funding was a metaphorical hot potato. Union leaders looked to the district and its spending on non-student-facing roles, the district looked to the state and its failure to fund the Quality Education Model (QEM), and the state remained non-partisan — although some representatives expressed support for the union. Hollands asserts, “The state has a part to play, the district has a part to play, [and] the board has a part to play, and when those parts are not getting played then the ones that suffer are our kids.”

Post-strike, both the union and the district have emphasized the importance of state funding, especially fully funding the QEM, which is an estimation tool employed by the Oregon Legislature. The QEM is informed by a Quality Education Commission of numerous educational experts, and identifies the cost of funding a “quality education.”

While fully funding the QEM depends on bipartisan agreement in an increasingly polarized political landscape, Governor Tina Kotek made other commitments after the contract agreement in an attempt to combat problems exposed by the strike. According to a press release from the governor’s office, Kotek is developing a statewide action plan to support student social-emotional health needs; partnering with the legislature to establish minimum teacher salaries and review school funding and creating the Office of Transparency within the Oregon Department of Education to make budget information more accessible.

Yet many question if more money will solve the fundamental issues as concerns over the breakdown of relationships between district and union leaders persist; after all, bills are not bandaids. At the Jan. 9 board meeting, Greg Burrill, a member of the PAT executive board, stated he believes we must change “the culture of PPS to allow for true stakeholder dialogue.” He looks to the superintendent transition as a crucial aspect of this change, but also highlights the need for “a disinterested peace leader who can bring healing to each party separately.”

How to begin conversations remains murky as the public dialogue between PPS and the PAT remains in the “Union Comment” section of monthly board meetings, which offers space for union leaders to speak and, with increasingly tight meeting schedules, no clear avenue for board members to respond. This often leaves union leaders feeling unheard. In addition, some community members feel this too closely mirrors the issues of the strike period; they point to it as an example of more conversations, between those in authority, that are inaccessible to a large portion of stakeholders.

Barrentine states, “Both the union and district are [such large institutions] so it’s hard because they feel above my level of control.” While broader societal change remains difficult, local change provides an avenue to get involved. At Franklin, Naegele explains that administration is “working to gather feedback from students, teachers, and staff on the best ways to provide support.”

Many students have directed their frustrations about the strike into such school-based engagement, but some are looking farther. Kupper adds, “I’ve personally noticed an uptick in myself and my peers using what platforms we have to encourage participation in labor movements and other protests locally and beyond.” As students continue to use their voices, there is hope that students will begin to be more included in district conversations.

Despite the learning loss of the strike, picket lines and packed board meetings provided another form of education for students. Seeing the strike and everything preceding it impact their teachers, friends, and family members illustrated to students the importance of participating in current events. Inflation continues to grow, labor movements gain national attention, and current high schoolers are reaching voting age; the issues the strike brought to the forefront will persist, yet now many students will feel prepared to engage with them.

As the aftershocks calm, one thing remains clear: years of built-up tension — at every level — didn’t disappear with the ratification of the teacher contract. While it’s important to acknowledge the difficulties of this time for the community, we must use these challenges to propel ourselves forward into a better society. Hope remains and ideally, so will faith in public education.