During the 1990s a massive culture shift changed Portland for generations to come. Today we have a sprawling cultural identity associated with art and music. We have thousands of small artists trying to make a name for themselves and beautiful nationally recognized venues, like the Crystal Ballroom. According to a report from Workamijig, a company that has created a “marketing project management software designed just for creative teams,” Portland ranks as the third most creative city in America. According to the report, Portland has “5,136 artists and musicians, 29 music festivals, 49 museums, [and] 20 film festivals,” with the number of artists only including those whose job it is to create, leaving out the thousands of smaller artists. Portland is undoubtedly one of the biggest hubs for creativity and musical expression in the entire United States.

A large catalyst for our modern creativity was the rock, indie-rock, punk, and grunge music that melded together, creating one unique and thriving renaissance of musical creativity during the 1990s within Portland. Artists like Elliott Smith put this scene on the map, with Smith’s monthly Spotify listeners at a staggering three million despite his passing two decades ago. Local recording giants, such as Larry Crane, founded studios allowing hundreds of amazing artists the ability to create their unique sounds. Bands such as Sleater Kinney, Heatmiser, Quasi, the Dandy Warhols, and so many more created a vibrant scene unlike any that have come before it, and any that have come since.

Before this scene transformed Portland for the better, the city was in a dark place. Portland used to be known as “Skinhead City.” Groups like “East Side White Pride” and “Aryan Nations” plagued the Portland community, attempting to recruit members to create a politicized fascist movement. These skinheads would attend shows, attempting to pick fights with non-fascist people, ruining events. The height of this was in 1988, when members of “East Side White Pride” murdered an Ethiopian immigrant, Mulugeta Seraw, right off 30th and Burnside. After the murder, members of the group who participated in the crime were put on trial and sent to prison. Scott Fox, the bassist in Crackerbash, states that this “led to the skinhead scene dissipating.”

With the ending of such an ugly scene, came the birth of a new one, with bands like Crackerbash, a punk-pop band that formed in 1989. Calamity Jane was formed in 1988 and released their debut album “Calamity Jane” in 1989, and Dharma Bums was created in 1987, releasing their debut project “Haywire” in 1988. These bands, along with many others, combined with musical venues like Satyricon and Berbati’s Pan, were the catalyst for the growth of the scene in Portland, sparking a new era of creativity, and much more inclusive self-expression.

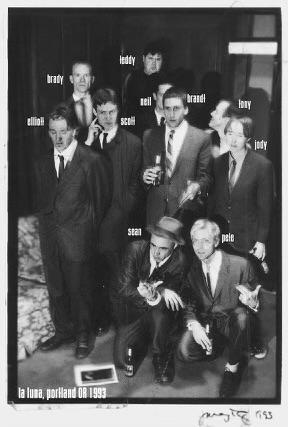

Leading into the early ’90s (1990-92), a lot of other important bands were formed, such as Heatmiser, Hazel, and Pond, which included prominent figures within the scene like Elliott Smith, Jody Bleyle, Tony Lash, Sam Coomes, Pete Krebs, Neil Gust, and many others. Important venues such as La Luna and X-Ray Cafe were also created within this period. La Luna was one of the biggest venues to come out of the ’90s, hosting bands like Nirvana, Heatmiser, and the Dandy Warhols. Due to it also being an all-ages venue, it allowed younger audiences to discover the scene. One of the Dandy Warhols’ members, Zia McCabe, said she “grew up watching and discovering bands there.” X-Ray Cafe was an all-ages venue as well. Cavity Search Records was also founded during this time, being an important label for releasing and growing music within the scene. Calamity Jane also played their last show in Buenos Aires with Nirvana in 1992.

Approaching the mid ’90s (1992-94), more bands started to appear, and previously existing ones started to release more important projects, like Heatmiser’s “Dead Air,” Pond’s self-titled project, and Hazel’s “Toreador Of Love.” Sleater-Kinney was another important band formed within this period. It was very influential in the scene and a part of the “Riot Grrrl” movement. Riot Grrrl was an underground feminist punk movement that released songs addressing rape, domestic abuse, racism, sexuality, and women’s empowerment. Elliott Smith also released his first solo project, “Roman Candles,” in ‘94 under Cavity Search Records.

Laundry Rules Recording was also started in ‘94, being the precursor to another important studio, Jackpot! Recording Studio, founded by Larry Crane. According to Crane, “Bands like The Maroons, and Satan’s Pilgrims recorded there,” along with many others. Crackerbash also ended during this time, performing their last show alongside Heatmiser and Hazel at La Luna. The famous, and beloved, X-Ray Cafe also closed in ‘94.

The mid ‘90s (1994-96) was the peak of this musical era; the Dandy Warhols were founded in ‘94 and released their first album “Dandys Rule OK.” Heatmiser released their last official album together as a band in ‘96, “Mic City Sons,” before disbanding that same year. The project was a different style than the usual rock sound of the band, showing more of an evolution within the sound of the scene over time. Smith also released his self-titled project in ‘95. The Band Quasi was formed in this era, consisting of Sam Coomes and Janet Weiss.

The Magazine Tape Op was founded in ‘96 by Larry Crane and served as a centerpiece for learning about music in Portland. Crane states that it’s about “making records, recording albums, and giving a platform to artists and producers.” Hazel also released their second studio album during this time, leading to even more growth in the scene, eventually starting to reach its peak in popularity.

The latter half of the ‘90s (1996-98) started to see the slow evolution of the scene’s increasing change. Bands like Hazel, Team Dresch, and others disbanded. The notable Laundry Rules Records ended due to Crane “wanting to move the studio out of his home and into a more commercial space” as the thriving and rapidly growing scene forced Crane to expand.

Jackpot! Records, founded by Crane and Smith in 1996, is a renowned independent record label based in Portland, Ore. Initially established as a recording studio, Jackpot! Records quickly became a hub for music enthusiasts in the city. Crane served as an engineer and producer at Jackpot! and personally recorded many of the scene’s biggest artists, artists like Elliott Smith, Quasi, and The Joggers. Crane produced music for many other artists outside of just this local era such as Cat Power, contributing to the rich musical tapestry of the Pacific Northwest and supporting local and independent musicians.

At the end of the ‘90s (1998-2000), most of the earlier bands had ended, and more notable ones from the mid-’90s did too. Elliott Smith released some of his most important albums too: “Either/Or” (1997) and “X0” (1998). Notable magazines like “Puncture,” and “The Rocket” ended in 2000. There is no official end to the scene, as the scene saw an evolution, not a death, as the years went on. But the year 2000 marks a transition from the prime years of the 1990s into a new modern era of Portland music.

Throughout all of these changes to the scene, all the music made in this era shares commonality in the distinct connective and emotional feelings of the music. As Crane remarks, “I have a tangible feeling about it, but it doesn’t quite [translate] to words.” He continues, saying, “There was a casual friendliness to it.” The scene wasn’t just made up of great musicians, but it was made up of friends. “[There was] a lot of synergy, it was a little bigger than it all really was, bigger than the sum of its parts,” Crane said. There were frequent “jam sessions at each other’s practice spaces,” spoke Gilly Ann Hanner, a member of Calamity Jane. McCabe states, “I feel like this time will be remembered as one of the heydays of the Portland music scene.” McCabe elaborates, saying, “We had so much time to play and be creative. The city felt like it was all ours.” The scene was rich with infrastructure and considered a very “healthy scene” by Crane. Over time, many of the artists who once played on the stage stepped behind it to continue supporting the scene and the infrastructure that allowed so many artists to share their talents.

Artists constantly gigged shows, as the only way to get your name out there was to “[get] your physical butt out there,” Hanner remarks, “it was very hands-on and organic.” Often artists would go to each other’s shows, using posters strung up on telephone poles to know who was playing, as well as using those poles to promote their shows. “Stapling concert posters to telephone poles in the rain kinda sucked,” comments McCabe.

Tickets were often as cheap as $5 a show, making them accessible as a nightly activity. Every night, musicians could share their art, learn from one another, and build even deeper relationships. As Tony Lash (Disclaimer: This source is the father of one of the authors of this article) puts it, “I liked the relationships, I made a lot of friends, [I was] out a lot doing stuff. Touring could be really fatiguing but also very fun,” he continues, saying, “and the creative energy, which is what drew me to music in the first place.”

Musically speaking, while the subgenres differed drastically from band to band, one common trait persisted throughout the scene: “[the music] was approachable,” according to Fox. Not only was the music approachable but it was rich with emotion, and musical complexity. Crane states there is “enough to chew on,” describing the music as extremely thought-provoking and “nourishing.” The scene created a blend of many different sounds and unique musical profiles. “I think there are elements of many genres incorporated into the music I make and the result is a combination of my interpretation and how I deliver it,” said Hanner. The music was loud, emotional, and tailored to each individual artist. For example, for Hanner, they “connect with how the distortion of high volume and shouting vocals makes [them] feel.”

The smaller, more local scene allowed artists to focus on their craft, producing excellent music as artists were able to specialize their sound, “a sound that was kind of dark and moody” as Fox puts it. As Crane describes, “Being able to create stuff that’s a little left to center, or not trying to be mainstream gives you that freedom to do something new, and that’s the important part.” However, the smaller regional scene led to some problems in growing recognition. “If the scope of the potential audience is smaller, then a record label may question investing in it, or maybe [the artist] will question if [they] should invest in it,” explains Crane, “or you could make something boring and have a huge audience.” Today many of the world’s largest artists create much more general and universally palatable music to appeal to much larger audiences and avoid that very same issue, according to Crane. Artists like Ed Sheeran, Taylor Swift, Drake, Arianna Grande, and many more have massive audiences of millions of people, meaning their music must be tailored to fit such a wide audience.

As time went on and the scene changed, once prominent bands dissolved, and new faces joined the scene. “More and more youth moved here to get in and be around bands. This diluted the scene a bit,” explains McCabe. As Nalin Silva (Disclaimer: This source is the father of one of the authors of this article), a long-standing Portland artist and audio engineer, puts it, “People not from Portland moved here wanting to be a part of what Portland had, not really knowing what it meant.” He elaborates further on the topic of change, saying that despite that, “change isn’t always a bad thing. Change is inevitable, even if it’s scary.” Crane shares a similar sentiment: “It’s just different. It’s a different focus, but it’s very cool to see.” He elaborates further, saying, “People from different music and culture backgrounds playing stuff together.” Crane cites a large reason for this growth being the fact that people simply have much more “access to recording software.”

A stark rise in the cost of living within Portland — the average selling price of a home in 1990 was just $96,000, compared to $289,000 in 2009, according to the Oregon Metro Department — and the closure of many prominent venues caused a gradual end to the peak of this ‘90s scene. Still, some of the biggest bands during the ‘90s are some of the biggest bands today, and bands like the Dandy Warhols, Quasi, and Sleater-Kinney are still active and performing bands. However, Elliott Smith tragically passed away at the age of 34 in his home in the year 2003.

Coming out of the end of this ‘90s golden age came a new era of emotional and resonant local music inspired by the music of the past, crafted by a new generation of emerging youth rock artists rising through Portland. “This era, and every era of music has an effect on the music that follows it. I think it is cyclical and younger generations mine the past either intentionally or subconsciously for inspiration,” says Hanner. The effect of the 90s era isn’t just local, but national. Artists like Alex G, otherwise known as Alex Giannascoli, have cited Elliott Smith as a huge influence on their own music. “I’ve been really influenced by Elliott Smith’s singing style,” said Giannascoli in an interview Geoff Nelson published to the media website Consequence. Alex G has over 7.6 million monthly Spotify listeners, showcasing the scene’s enormous impact, with the bands of the era bouncing off each other, growing and improving, and shaping many of the modern indie stars we have today. As Crane puts it, “I see bands all the time half my age or less that are inspired by bands I used to see. I think there’s always plenty to mine from the past.”

Looking back on Portland’s vibrant ‘90s music scene, the true love, passion, and community music brought is on full display in the songs made during the era. Songs like “Needle in the Hay” and “Between the Bars” by Elliott Smith, “One More Hour” by Sleater-Kinney, “Our Happiness is Guaranteed” by Quasi, “Ride” by Dandy Warhols, “Rest My Head Against the Wall” by Heatmiser, and so many other songs pour human emotion into sound. The hundreds of amazing artists and bands of this time created a bedrock foundation from which generations henceforth will be able to build their interpretations and unique sounds. By remembering this music of the past and celebrating the music we have today, the sounds of the past can continue to inspire the sounds of future generations for many years to come.