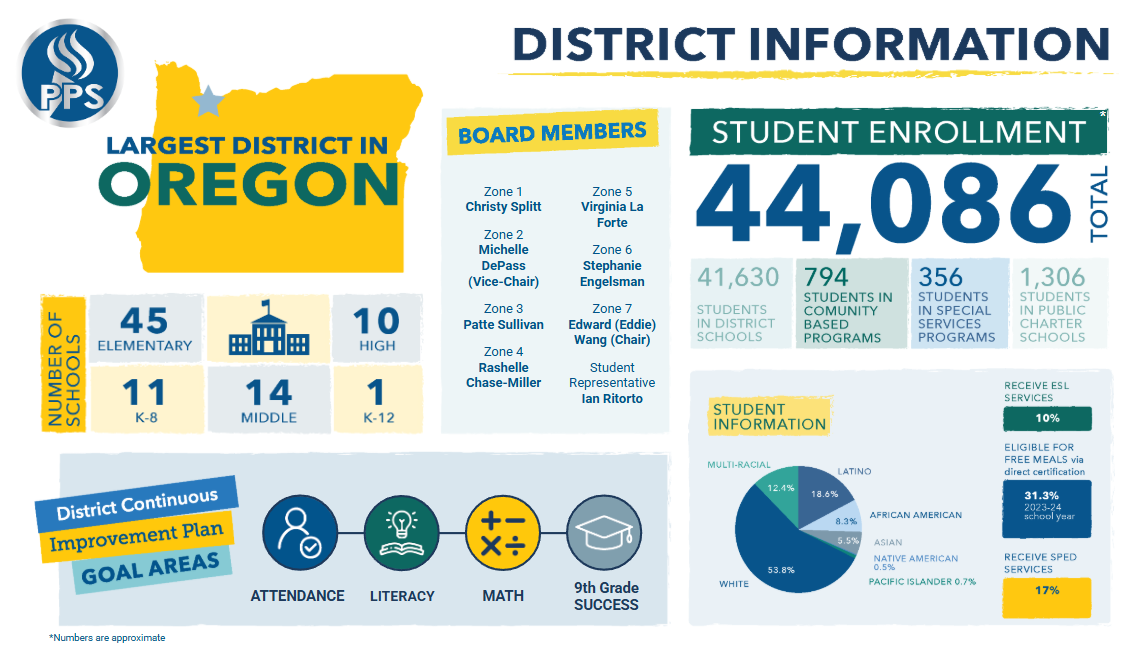

Last month, Portland Public Schools (PPS) revealed “Equitable Grading Practices,” a proposal aiming to limit racial disparities in grading. If approved, new guidelines would ban grades for participation, behavior, extra credit, and homework; additionally, the plan would remove penalties for late work and cheating. This new grading system would now solely reflect students’ scores on summative assessments and would, in theory, be an equitable reporting of student proficiency in various skills. The proposal was first announced in August, in a handout summarizing the initiative.

The district aims for teachers to better “consider a student’s background” while grading, saying there are racial inequities in PPS’ pass/fail rates. They attribute this to a few things: students’ after-school responsibilities, teachers’ implicit bias, and a lack of accuracy in the current system.

If approved, the proposal could be seen in middle and high school classrooms as early as 2025 and would require behavior, timeliness, and homework to be reported in non-academic ways. The handout says, “Grades [would be] based on valid evidence of a student’s content knowledge, not on evidence that it is likely to be influenced by a teacher’s implicit bias or reflect a student’s environment.” PPS hopes to foster an environment that prioritizes student growth over time, advocating to normalize feedback, allow retakes of both assignments and tests, and provide clear standards. Senior Director of High School Core Academics Dr. Filip Hristić says, “Teaching excellence is about being clear with students about their learning target and what steps they need to take to reach that target.”

Additionally, the envisioned classroom environment would “allow students to retake assessment[s] or redo assignments and provide multiple opportunities to demonstrate proficiency on learning targets.” The plan would ensure teachers leave feedback on non-summative assignments instead of just assigning a grade. However, Angela Bonilla, president of the Portland Association of Teachers, supports the concept but worries that “when we allow students to provide multiple versions and expect feedback, this is additional work for educators.” The district was unable to provide a response by publication, so it’s unclear if the district has taken this into consideration.

The plan is based on a grading philosophy that thinks penalizing students for factors that are easily impacted by their environment, such as turning in homework late, creates unfair grading bias. Hristić says these factors “should be treated as important, but also different from assessing students on what they know and are able to do.”

If implemented, “Equitable Grading Practices” would ask teachers to provide “alternative consequences for cheating.” Students caught cheating could retake assessments, instead of receiving an automatic zero or point deduction.

Students would now be graded solely on “summative assessments” which have yet to be defined by the district, but typically refer to end-of-unit projects or tests. New report cards would utilize a zero to four scale, instead of the traditional 100-point scale. Students wouldn’t receive scores of zero and one, as the plan also implements a minimum grade floor of 50 percent.

PPS has received much backlash since the proposal was announced in August, with many media outlets saying it’s lowering standards in education and letting students pass courses without trying. “They will neither practice nor master any skills. Why would they, if all the school district is going to do is give them credit for their ‘work’ whether it is good or not, on time or late, or even whether it is not done at all?” writes Zachary Faria from the Washington Examiner. This backlash, however, overlooks the fact that 100 percent assessment-based grading would require a student to master the skills they are tested on.

Considering minority and low-income students average lower scores on standardized tests like the SAT, measuring performance purely on assessments could make disparities in grading even worse. The plan may standardize grading, but it doesn’t necessarily remove racial disparities within it.

The handout says that many teachers adopted their own version of “Equitable Grading Practices” at the start of the pandemic which has since “led to a mosaic of grading practices across schools and across the district that is confusing to students and families.” A course taught by two different teachers may have completely different standards; however, it’s not out of the ordinary for teachers to grade according to their preferences.

Teachers currently control the grading of their students in PPS, but Bonilla says they’ve “had experiences in the past where administrators would go into Synergy or Canvas [platforms PPS uses to grade] and edit student grades after educators submitted them.” This prompted the addition of language into teacher contracts that prohibits this behavior and makes the execution of “Equitable Grading Practices” sound improbable. “Student grades issued by a teacher shall not be changed by a supervisor or altered due to software limitations of the district’s grading system unless a substantive reason clearly exists,” states the contract. Bonilla adds, “We don’t want a false inflation of grades that doesn’t actually support students, but a system that ensures educators can provide the skills and feedback students need to show proficiency.”

“Equitable Grading Practices,” which largely draws inspiration from Joe Feldman’s book, “Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How It Can Transform Schools and Classrooms,” is putting a name to the shift in educational priorities we’ve seen in schools lately. While a steep change, this isn’t the first time we’ve seen plans to standardize the grading process; a similar proposal was almost brought to fruition through an Oregon law in 2013. While “Equitable Grading Practices” is new and specific to just PPS, equitable grading certainly is not.