Content Warning: This article includes mentions of suicide, sexual violence, and cyberbullying.

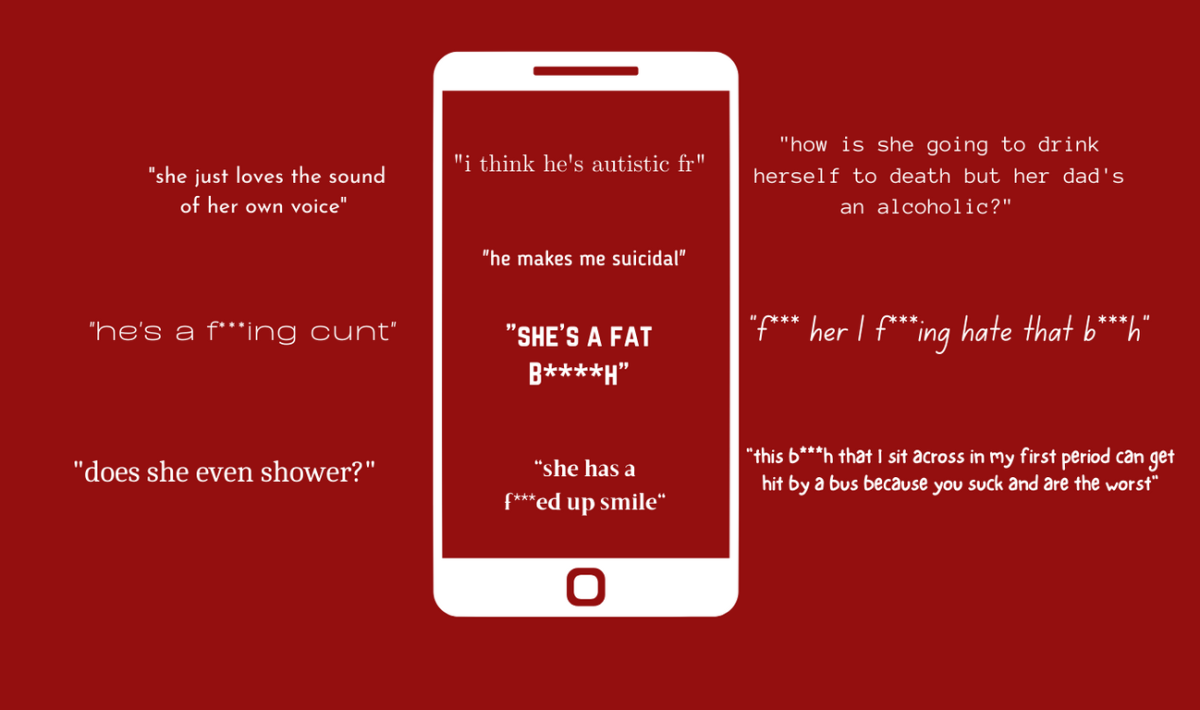

Cyberbullying is the use of technology, media, or the internet to bully an individual, via threatening or harmful posts or messages. This is an increasingly common phenomenon, according to a study done by Forbes in Sep. 2021. It can be difficult to track, as posts and messages can be quickly deleted. And while some cyberbullying is done with the identity of the perpetrator(s) visible to the target, a sneakier, anonymous, form of cyberbullying can be easily done through fake accounts, or in the case of confessions pages on Instagram, anonymous Google Forms responses.

Campus confessions pages are not a new practice; a 2013 New York Times article titled “Owning Up” described the occurrence of these pages, originating from the University of Wisconsin, which garnered 500,000 weekly views on Facebook. But Franklin High School (FHS)-specific pages became more popular in 2021, sparked by the creation of confessions pages at other Portland schools. Starting with more lighthearted accounts posting photos of sleeping students to bad parking around campus, some became meanspirited quickly, such as the confessions pages. On these, anyone can anonymously submit a “confession” to a Google Form. The submissions are then posted publicly on the account and can be shared and reposted indefinitely. The confessions range from funny, niche commentary on school-specific topics, to serious threats or accusations of assault.

The Instagram account @fhsconfessions_. is credited with re-kindling the interest in online confessions pages at FHS. At the beginning of its life, the owner(s) would post nearly every day, and the page was flooded with submissions, both from FHS students and random “internet passersby” who had no connection to the school. As far as I can tell, the owner has generally blurred the names of students in negative posts, occasionally leaving a name unblurred. Posts on this account tend to be more harmful than on similar accounts, and the aspect of blurred names takes away many possibilities for conflict.

One account that has risen to prominence recently is @fhs_muchbetter_confessions, and @fhs_muchbetter_confessions2.0, the second version. This account quickly grew popular because of its riskier, more inflammatory content, and the fact that names are left unblurred. Its posts would spark arguments in the comment section, and from my observation, tend to target certain individuals. Sometimes, an entire week’s worth of posts would be mainly about two or three people, in a borderline “mass harassment” fashion. The Google Form description was “confessions!! please, say anything and everything…” which participants took full advantage of. The account was suspended in late February, but the owners promptly created a new one, which as of Mar. 4, has no posts.

Some posts on this account said things like “I f***ing hate [unblurred name] she such a b**ch she grosses me out,” “F**k [unblurred name] bro he can die in a hole,” and “I agree with that other [post], [unblurred name] should die, nobody likes him and he’s just looking for attention in all the wrong places.” A few things that I wondered as I scrolled through this account were: how do the owners choose to curate their page? What submissions do they post or not post? And what is the reasoning behind choosing to leave names unblurred? I corresponded anonymously with the owner of this account about these choices. “We chose not to blur names because it makes it more interesting but if someone does not want their name in posts we immediately take the post down,” said the owner(s). “I do not post everything people submit and I usually don’t post stuff that’s just flat out terrible stuff people are saying about each other or when it’s about someone who has asked not to be in posts.” But what is “flat out terrible,” if not threats of violence or telling individuals to hurt/kill themselves?

Franklin student Max Risner (9), who has been implicated by these accounts, is sharing that they were posted about on one of them as an act of retaliation. “I called someone out for being racist. And then they were the person who told me to kill myself. And they also said I’ve body-shamed people which I’ve never done, spreading lies about me.”

Daivon Hendrix (12), reflects on the purpose of these pages: “[Confessions pages are] straight negative, nothing good comes out of them, just public cyberbullying usually.” Some of the content on the pages is positive or neutral. One post from @fhsconfessions_, posted on Oct. 13 reads, “Whoever needs to hear this: You’re a bad bitch who can f***ing do this! Don’t let nobody tear you down. Stick to your wits, your muscle and your education. Listen to LIZZO and feel empowered!” Other posts simply state who people have crushes on, in fact, @fhs_loveconfessions solely post confessions about who people like, or find attractive. Out of all of the accounts, this one is by far the most active, and positive. “Some of [the posts] are funny, like, the ones that are like, ‘oh, yeah, I like this person. I like that person.’ Stuff like that. It’s like, there’s no harm done with posting those, right?” says Risner. “But there’s also [pages] telling people like ‘oh, you should kill yourself’ or ‘this person is doing this’ when it’s not true.”

Near the end of January, an account called @fhs_burn_bookk was created by an anonymous owner(s), and to some, its creation crossed over the thin line from “funny” into the realm of serious bullying. It was only up for a day, but featured multiple targeted posts about individuals at FHS. Instead of screenshots of a Google Forms response, it took the form of a podcast, posting minutes-long audio recordings “exposing” embarrassing or “bad” things each of the targets had done. Many social-media users have been desensitized by scrolling past so much online harassment in the form of posts, that when people heard, rather than saw, the horrific comments about classmates and friends, they were jarred into reality. Multiple friends sent me the link to this account, one saying, “this is so not okay… it’s like sickening.” This account likely got taken down quickly because viewers were so shocked and horrified to witness this cyberbullying in a new form, that they reported the account to Instagram’s Help Center.

Some students feel concerned about the effects of these pages on teens’ mental health and well-being. “I think that they are funny until they aren’t and then they become super harmful to people’s mental health. Especially because it seems that there are certain people targeted,” says Charlotte Storrs (11).

Another common type of submission on the confessions pages—one that can quickly spark arguments—are “call-outs.” These are typically related to sexual abuse or assault, and pages like @fhs_much_betterconfessions post them frequently, without blurring the names of those accused. “I think it’s important though, to have these accounts, because I feel like it does give victims a place to say something about [their assault] because a lot of them haven’t come to a place where they’re able to have that be something known to everyone,” says Risner. “But if they’re able to spread [the story of their assault] on [the pages], then other people will be able to avoid that person potentially, to avoid that from happening to them to other people.”

These internet call-outs are reminiscent of a Snapchat era during Spring 2021 in which Portland teenagers spoke out about sexual abuse or assault they had experienced, and placed their alleged abuser on an online list. This list was then shared and reposted many times under the title “Rapists/Abusers/People to Avoid- PORTLAND OREGON.” For some, sharing their story through Snapchat was important to both heal and make sure no one else experienced a similar thing with the person that hurt them. But quickly, the list got out of hand, with names being added as “revenge plots” rather than actual allegations. Now, in 2023, accusations on confession pages bear resemblance to the Snapchat list. Anonymous posting is a slippery slope, no matter what the content. Robyn Griffiths, FHS Vice Principal who manages Title IX concerns for FHS, recommends that students reach out to her or another trusted adult if they experience sexual violence rather than posting anonymously. “If someone has been harmed in some way, they need to be able to, either anonymously or not, send a Title IX report, come talk to one of [the admin or] come talk to a counselor. So if an investigation needs to be open, it gets open.”

In an email to FHS teachers and staff on Feb. 3, 2023, Griffiths alerted any unknowing teachers about the pages and gave them information on how to report accounts. “While we fully respect the privacy of our students and acknowledge their right to use social media, we also have an obligation to uphold a safe and respectful learning environment, which we know can easily be compromised with harmful social media posts,” read the email, in short. Reporting posts only goes so far, as Griffiths explains; in her experience, it has been easier to take down accounts that have videos or photos depicting violence, but whenever she attempts to report a confessions page, Instagram says: “‘We reviewed your input and we are not removing it at this time.’ They don’t go into any further detail on that,” she recalls. So instead of trying to battle the pages when they are already posted, FHS administration is looking to prevent things from being posted at all.

“What we’re planning on doing is for next year, in the first two weeks of school, … is to have a social awareness campaign of what you can do to prevent [cyberbullying], or if you’re a victim of it, what you can do if you’re being harmed in some way,” she explains. “There’s disciplinary measures that have to take place, but if we don’t know who [posted the comment] because a lot of times these are anonymous, then we have to say, ‘Okay, you’re being harmed, your mental health is at stake,’” she continues, “so we have social workers and school counselors who can help you with that.”

Elise Bradley, FHS Restorative Practices and Student Support Specialist, is looking to implement more support systems in the coming years for students struggling with cyberbullying and other stressors. She values doing “pre-work,” which is taking preventative measures to stop the spread of hate and bullying, while also providing aid to students who have fallen prey to bullying, online or off. “How do we structure systems so students have outlets for issues?” is a guiding question for her work. From a student’s perspective, Risner agrees that the school is in need of more supports, especially for victims of sexual violence. “Maybe having a separate place where students who have gotten assaulted, sexually assaulted, anything like that, where they’re able to have somewhere anonymously to share that,” he says. He explains that students need a place to talk about their trauma without it being mixed with untrue or negative comments. “Obviously, if there’s something in [the account] that’s an actual allegation, and then [the following slide is] something completely false and negative, and then [the post gets taken down], it’s also not spreading awareness of what’s going on [with the allegation].”

Online confessions pages have had serious and negative impacts on many FHS students, and the FHS climate as a whole. Anonymous bullying is not okay, and for students who may be witnesses to or victims of online bullying, reporting Instagram accounts that harbor negative content about community members is a first step. But getting help to stop the bullying is also extremely important. Reaching out to school counselors or trusted adults is a good way to heal from harm done by things posted, and also to interrupt online perpetrators. And for those who feel the urge to post, submit, or share something that isn’t positive or neutral, envision the impact of your words. Think twice before posting, always.