When you ask anyone to describe an Asian-American, they would typically respond with things like“smart,” “nice,” “hardworking,” “docile and submissive,” “obedient,” “uncomplaining,” “never in need of assistance,” and “usually well-off.”

These stereotypes fall under the model minority myth, which is defined by Harvard Law Education as “a minority group [that is] perceived as particularly successful, especially in a manner that contrasts with other minority groups.” A study conducted by the nonprofit organization Leading Asian Americans to Unite for Change (LAAUNCH) addressed the causes of racism, discrimination, and excavations on the attitudes and perceptions of Asian Americans in the United States. This study was yet another awfully familiar reminder that Asian Americans are still deemed as the “model minority.” They conducted a poll asking respondents to provide three adjectives that describe Asian Americans, and the most dominant answers were “smart/intelligent,” “hardworking” or “from a certain country,” like China.

According to Forbes, “the phrase model minority was coined in 1966 by a sociologist writing in the New York Times about the success of Japanese people in overcoming the effects of discrimination through their supposed inherent industriousness.” They also added that since then, the model minority myth has become a well-worn cultural trope—one that is overused and that needs to be shut down.

Despite the stereotype’s “positive” implications, this myth perpetuates the fallacy that Asian Americans are always more academically, socially, and economically successful than other minorities, which then pits people of color against each other and pushes a wedge between marginalized groups because one is “more socially acceptable” than the other. After World War II, this myth of Asian Americans and their collective success grew and was used as a racial wedge against Black Americans. The model minority myth was also held to minimize the role of racism in the struggles of Black Americans. White people frequently utilize this phrase and the associated ideas to create distance between groups who have all endured the effects of white supremacy.

Not only does it affect the relationship between Asian Americans and other minority groups, but it also impacts them personally. For Asian Americans, this model minority concept deteriorates their individuality, characterizing them as people who think, look and act the same way, which fails to recognize the diaspora based on their cultures, traditions, traits and other attributes. It puts them in a singular box which ignores their individual experiences, struggles, and the discrimination they’ve each faced.

The model minority myth also sets unrealistic expectations on Asian Americans of all ages and genders. Sentiments such as saying that an Asian person got good grades because they are Asian is unfair because it basically voids out their long hours of hard work and perseverance. Not only that, but it also strengthens the harmful “you are what you are because of your race” narrative, which could also lead to toxic and unrealistic expectations. I had a conversation with a friend before, regarding their math homework, when they said that I only got good grades in that subject because I’m Asian.

No, it’s because I worked hard for it. I got an A because I strived for it and spent hours doing homework, calculating x, y, and z and understanding shapes that I don’t even care for, despite the numbers already floating and flying inside my head with no final destination in mind. So no, I didn’t have good grades just because I’m Asian.

In addition to the math chronicles, something I turned a blind eye to for years is that, ever since I moved here my freshman year, two Franklin teachers have not been giving me the same help in class compared to my non-Asian counterparts. I never realized this until I came across the model minority myth.

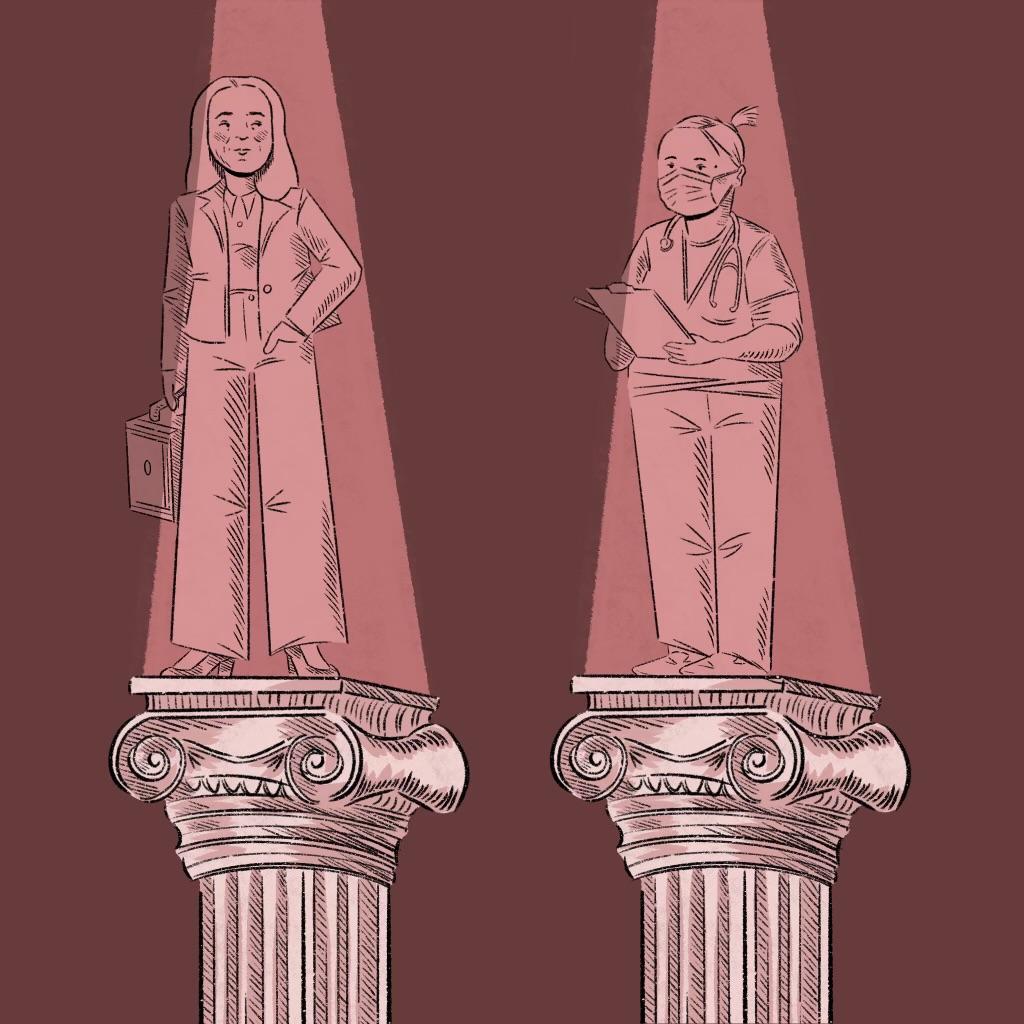

Asians, particularly Asian children, bear the burden of living up to societal expectations. Being expected to be a perfect child who gets straight As and is hungry for success undermines their self-esteem and calls into question their worth as a person. It also places unreasonable expectations on Asians who may not be as traditionally “smart” as others. These expectations are placed on them not only by society but also by their own families. Being compared to siblings or cousins is a big thing in an Asian family. Not being as bright as cousin A or pursuing a career as a nurse or doctor like cousins B, C, and D are common criticisms to be heard at family parties. Many Asian Americans may feel pressured to live up to these standards.

Franklin’s Asian American Association (AAA) President, Opal Rockett (11), shared a recent incident where the AAA received an invitation to an event which centered around the benefits of taking Advanced Placement (AP) classes. Even Franklin students who identify as Asian American who aren’t part of the club got an invitation to the said session. This again falls into the model minority stereotype and raises the sentiments that all Asian Americans are smart and therefore need to take a long list of AP classes. Questions like “Did other affinity groups receive this invitation?” arose. I double-checked with another affinity group, and Black Student Union adviser Keixa Bridges states that this invitation wasn’t sent to them at all. Which again, brings attention to the question, “are students who identify as Asian Americans the only ones invited to this session about AP classes?” Is it because we’re supposed to academically excel, conforming to the ongoing stereotypes laid upon us?

Rockett also commented on how others could improve their perceptions of these stereotypes of Asian Americans: “I think people could try to think critically and [try] to see everybody as [their own] individual person.” She also said that the awareness of these stereotypes is good and everyone must speak up whenever they hear something that is inappropriate and that feeds into the model minority myth: “[also try not to participate in the promotion of stereotypes.”

For most, including Rockett and myself, being stereotyped makes us feel misunderstood and erases our individuality. “When someone stereotypes me I realize how most of the time they don’t even realize they’re doing it, which is also irritating,” Rockett adds. It’s important to recognize if you are stereotyping others, whether it is through your actions or thoughts. You also need to recognize that Asian Americans are not monolithic people and each of them has their own experiences and struggles. That not everyone is as smart, wealthy, or overly nice as the media and society paint them to be.

Each person can help spread awareness and recognize our own mistakes in perceptions of Asian Americans while it’s not too late. I know it is easier said than done since these ideas toward Asian Americans have also been engraved into our minds and society, however, it is not hard to start educating yourself and others on this issue; it is never too late to advocate for change. Everyone can support Asian Americans by recognizing their diversity and not just characterizing them as people who act and look the same.