Most music has a pulse—that is, a steady rate that it moves that determines where notes land in time. The job of percussion in music is typically both to keep that time, and to keep that time interesting. Usually, that involves rhythms that subdivide the pulse into groups of two or three, but what often gets neglected are the rhythms that subdivide the pulse into more difficult numbers, such as five or seven, as well as the combinations of those subdivisions. The former idea is tuplets: any subdivisions of the beat that don’t, by default, appear in the time signature they’re in. This includes common subdivisions such as triplets, as well as quintuplets, septuplets, nonuplets—and any other number of ways to divide the beat. The latter idea is polyrhythms, where you divide a span of time into multiple subdivisions at once, whether it’s something as simple and common as a 3:2 polyrhythm, or something as complex as 3:4:5 on three different voices. Both tuplets and polyrhythms have a lot of uses beyond just musical novelty. But what are those uses? And how can you play them?

We’ll start with tuplets, as those are the more simple concept, and are necessary to make polyrhythms. The simplest way to learn a tuplet that you can’t yet play is more or less just trial and error. Get a metronome going (start slow) and begin by playing the closest subdivision that you do know how to play. From there, slow down or speed up towards your intended subdivision and count the hits as you play them. Then, adjust as necessary until you are consistently playing your intended subdivision. You’ll know you’ve done it right when you count the right number of notes and the first one always lands with the metronome. For example, if you want to play quintuplets, you could start by playing a four note subdivision with the metronome and then speeding up until you have five notes in that time span; then, adjusting until the one of the metronome always lines up with the one of the quintuplet. Once you have it down, practice starting and stopping so you can always recall the tuplet, try it at different tempos, and practice seamlessly switching between other subdivisions and the tuplet.

An important note about counting: since it’s really easy to accidentally play groupings you’re already familiar with, make sure that you’re counting actual numbers instead of any other syllables. The key exception would be when you end on numbers that are multiple syllables. The tendency when you’re counting something like seven can be to audiate it as se-ven, where the second syllable is actually the eighth note, and you only think you’re playing seven because that’s what you counted to. It helps to count the seventh note as sev, or something else that’s only one syllable, so that that doesn’t happen.

The other thing that can help a lot with playing odd tuplets is getting familiar with playing in time signatures based in those numbers. If you think of one bar as a unit rather than each beat, being comfortable playing in 5/4 is sort of similar in that you have five beats where you would normally have three or four, and it can help you think about quintuplets more fluently, since they are really similar, just at a smaller scale.

Tuplets can add a lot of interesting rhythmic variation to playing; quintuplets can, in a way, sound like laid back triplets, quadruplets can be fun to experiment with in three-based time signatures, and septuplets can sound really out of time, except you always land on one. And how you play them can really change how they feel. However, there is always the risk that because our ears aren’t used to hearing them, they can sound too out of time to sound good, because we just assume that they were supposed to be another subdivision, and it throws off our perception of the beat. Often, the remedy for that is actually introducing polyrhythms.

If you’re playing auxiliary percussion, or an instrument outside of the rhythm section, you probably won’t need this, because there will be other people keeping the time while you just make it more interesting. But if you’re playing an instrument like the drums, and you’re the main timekeeper, you might need to learn some polyrhythms in order to keep time while you play tuplet fills. When you learn complex tuplets, you’re using the metronome as a reference, and while you probably aren’t playing with one all the time, the idea is that you learn to know where the beat is even when you’re playing things that are totally outside of it. The audience doesn’t have that reference. To them, you are the metronome, and if you start playing something that sounds completely out of time, even if you know when to come back in, they’ll be lost. But, if you keep some aspect of what you were playing in the original time signature, then the audience has a reference. The tuplets you’re playing can suddenly sound really cool, because it doesn’t sound like anything they would normally hear, but it’s also clear where you are. If you’re playing in a band, still clear this with them beforehand, because they still won’t be able to keep time if you do this without warning unless they’re all also really familiar with these rhythms. But how do you learn to play in two time signatures at once? It seems really difficult, but the trick is: you never have to think in both at once. It’s still significantly easier said than done though. The way to learn tuplets was just to play along with the metronome. The idea here is the same, but the difference is, you have to be the metronome. As you go about doing things in your daily life, just try tapping your foot in time. Doesn’t matter what time, as long as it’s staying consistent. The goal is to get to a point where your tempo isn’t wavering, you can do other things out of time while you feel the time somewhere in your body, and most importantly, you can pay attention to it without interrupting it. That’s very hard to do, but once you get it, it’s worth it. If you play drums, you can put that metronome in the kick or hi-hat and basically play whatever you want over it. Learning to do that also opens the door for more complex ostinatos that you can keep time with and play over.

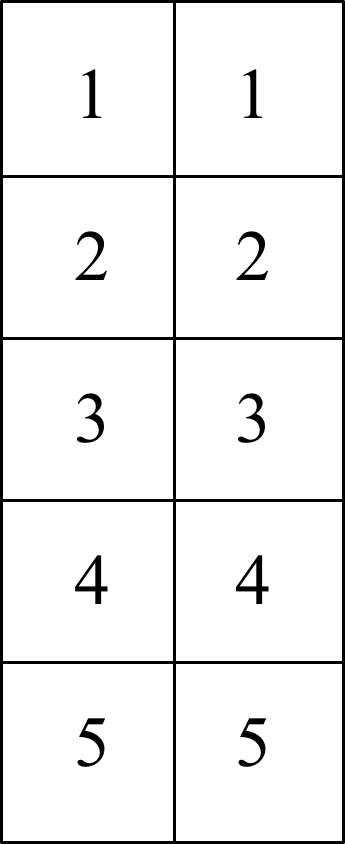

There’s one other way to learn polyrhythms that works really well if you want to employ more limbs or if you can’t quite figure a particular rhythm out, and that’s just to do the math. Find the least common multiple of all the subdivisions you want to play together and write out all the numbers up to that. Then, just mark where all of the beats will fall. It’s tedious, and you’ll have to play it slowly at first, but it lets you get a really good feel for where the beats actually lie without estimating.

Tuplets and polyrhythms have lots of great rhythmic uses, even if somewhat esoteric. Even if you don’t use them a lot, learning them is still one of the best things you can do to improve your sense of time. After all, it is just learning to play notes in time, just advanced time.

To any aspiring percussionists reading this—just remember—you should always find random places to play septuplet fills while keeping time for the rest of the band.