SOUTHWEST PORTLAND – A matter of weeks before the annual ‘Flock Fest,’ the Friends of Lincoln High School foundation is busy preparing for their premier fundraising event. In years past the event has been hosted at the luxury Sentinel Hotel, showcasing art from hundreds of Lincoln students and selling big ticket auction items, like international vacations and lunch with then-Oregon governor John Kitzhaber, whose son attended Lincoln at the time of the 2015 fundraiser. In 2018, fundraising events like this netted over $264,000 for the Friends of Lincoln Foundation, a 501(c)(3) which reported over $1 million in yearly revenue in 2018 and 2019 tax returns. The private fundraising entity is part of a group of wealthy, predominantly white schools which rely on hundreds of thousands of privately fundraised dollars per year to buy extra teachers and support staff for their schools. Across town at Rigler Elementary School, where 75.9% of the student body is considered ‘historically underserved’ by PPS, families collect cans in order to raise money. “When we’re looking at the data it becomes really clear that there’s pretty strong racial disparities between the schools who are able to buy additional staff through foundations and those who aren’t,” said Beth Cavanaugh, who has been working for years to change private fundraising policies as a lead organizer for the advocacy group Reform PPS Funding. Now, after an especially contentious year of debate, the Portland Public Schools Board of Directors may be on the verge of altering foundation rules to even out the share of funds.

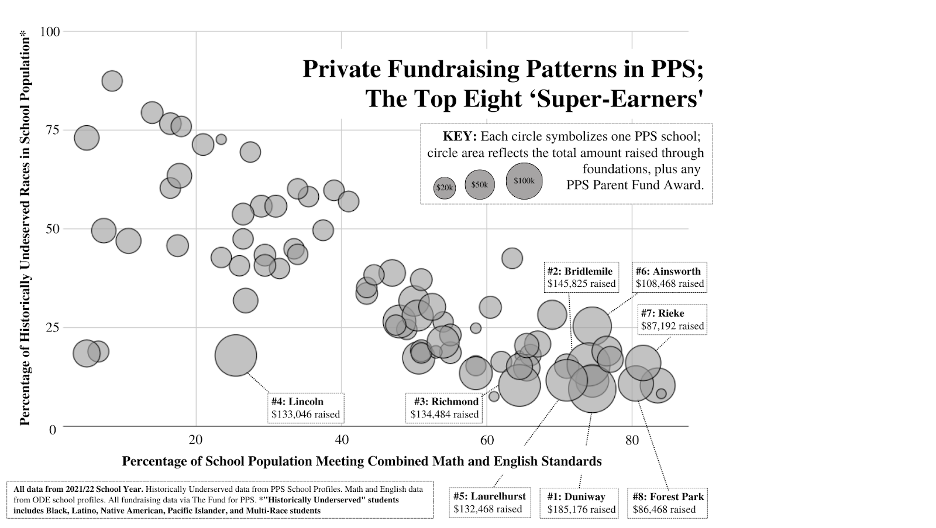

Currently, PPS policies allow for schools to keep 100% of funds raised under $10,000. Once a school foundation exceeds the $10,000 threshold, one-third of all following proceeds go to the PPS Parent Fund and are distributed to select, typically Title I schools, in the form of small grants. Parent Fund Awards ranging from $5,000 to $15,000 were distributed to 54 schools and learning programs across the district for the 2022/23 year, not enough for any recipient to hire a part-time educator. Meanwhile, Duniway Elementary School, the top earner in 2021/22, made $185,176 towards supplemental staff after the one-third deduction, hiring one full-time teacher and six half-time educational assistants. In 2021/22 the top eight fundraisers collectively put over $1.47 million from foundations towards additional staff, more than the other 73 PPS schools combined, based on district data. The disproportionate takeaways have propelled Reform PPS Funding to petition the board for changes to the foundation policies.

The group argues that creating a district wide foundation to intake all funds and distribute them among schools may be the solution. “I think that’s a great idea, I just don’t know if the income revenues will be the same,” said Friends of Lincoln President Mary Ann Walker who oversees private fundraising at Lincoln High School. Meanwhile, a coalition of high-end foundation presidents including Walker and others from Duniway, Alameda, Rieke, Forest Park, Beaumont, and Buckman proposed a plan that would increase the share of funds contributed to the PPS Parent Fund based on a sliding scale, where the more money a school raises, the greater share of it would be given away. If the sliding scale plan was implemented last year, an additional $8,043.37 would have gone to the PPS Parent Fund, a 1% increase. Cavanaugh commented on the plan, saying, “While I appreciate that there is some movement in terms of saying ‘okay, we will think about ways to contribute more and increase the equity,’ that plan doesn’t nail it.”

Creating an equitable funding model that boosts the outcomes of underserved students is at the center of the district’s focus following decades of disparities between test scores and outcomes of white students and those of students of color. PPS employs an equity funding model, which means that schools with the highest assessed need get the most funding. This results in schools like Lincoln High School, where 4% of students qualify for free and reduced lunch, receiving $7835 per student while Roosevelt, a high school where 35% students qualify for free and reduced lunch, receives $9401 per student. Walker commented on the funding model saying, “Lincoln, who doesn’t have a high need student body like Roosevelt, still has high need kids … foundations were put into place over 25 years ago to enable schools to kind of fill those gaps.” Similarly, Save PPS Foundations, a pro-foundation advocacy group, states on its website that “the problem is that we still have underserved students at ALL schools, along with students with special needs or learning disabilities, and with the less funding per student at affluent schools, those students are getting left behind.”

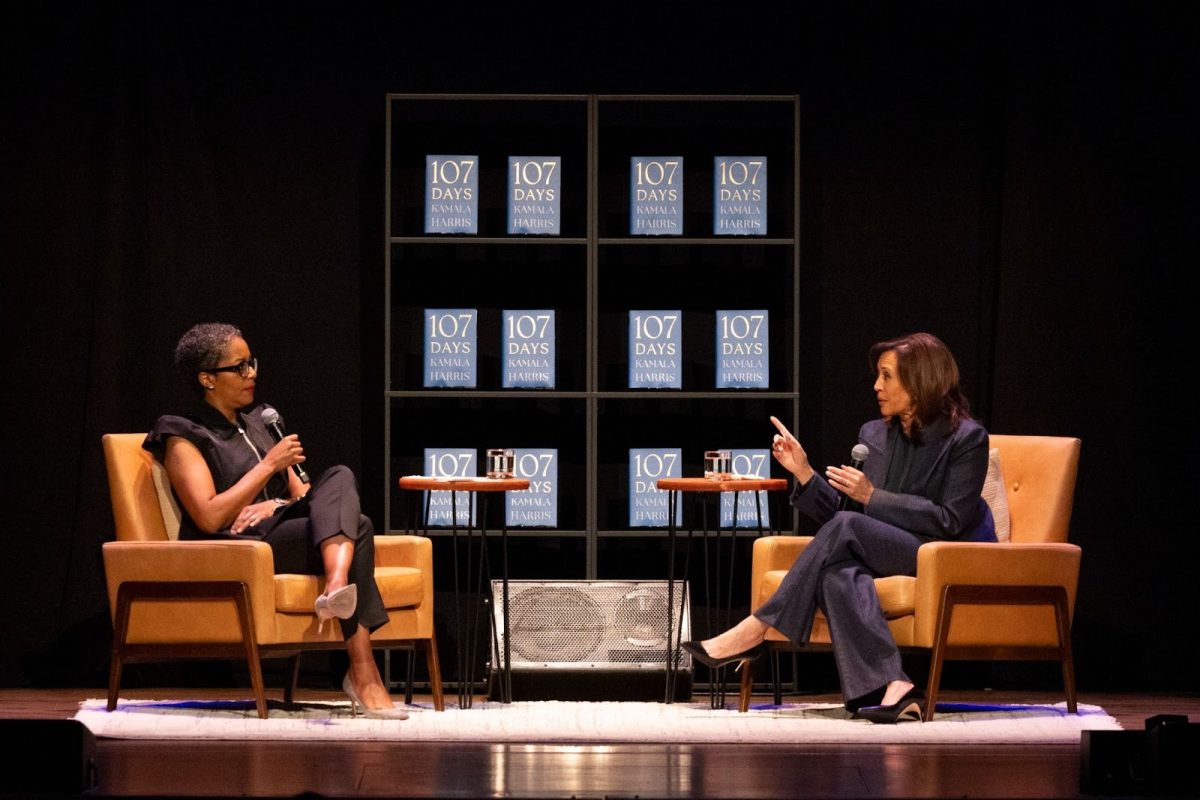

Data from the Oregon Department of Education’s 2021/22 School Profile’s casts doubts on these claims. Schools like Lincoln have a higher rate of historically underserved students who are regular attendees (59%) compared to Roosevelt (31%). In addition, 92% of students with disabilities and over 95% of students on free and reduced lunch at Lincoln are on track to graduate while, at Roosevelt, just 68% of students with disabilities and 75% of students on free and reduced lunch are on track for graduation. PPS Board Member Michelle DePass backs up the information, saying, “Chances are the one or three underserved kids in an affluent school are still in a better position to get the help that they need than schools that have larger numbers of kids living in poverty.”

Despite the data, Save PPS Foundations continues to suggest on its website that cutting foundation funding to affluent schools will “further divide our school district into silos of ‘haves’ and ‘have nots,’” warning of potential adverse outcomes for students of color if private fundraising is altered. Portland Association of Teachers (PAT) President Angela Bonilla raises questions on this narrative, saying, “I think foundations move us further away from that reality of what an equitable and fully funded school system can look like … Our argument is that, if [affluent schools] need it, that probably means everybody else needs it, so why are we allowing only certain groups to be able to fund FTE to their sites individuals needs while ignoring the individualized needs of other schools?”

The dispute has continually centered itself on race as both sides try to argue that their plan will best serve BIPOC students. The role of racial justice in foundation reforms bluntly surfaced at a Board of Directors worksession in December, where PPS Board Chair Andrew Scott said, “[Foundations] funding [staff] is unfair. And I think going beyond saying it’s unfair, I think we need to call it out as inherently racist.” Walker responded to Chairperson Scott’s remarks, saying, “I was shocked by those comments. I thought they were outlandish. Basically, that’s accusing really well intentioned parents who are just volunteering at their kids’ schools of promoting racist activites, which is not fair.”

In the same meeting, DePass said, “Buying people leaves a bad taste in my mouth.” She later elaborated on the statement, saying, “I used the words ‘buying people’ because I was thinking about slavery. I was thinking about who’s doing the buying and also just how inequitable it is to be able to have the privilege to buy people.”

Currently, historically underserved (Black, Latino/Hispanic, Pacific Islander, or Native American) students make up an average of 15.4% of the the top eight super-earner’s school populations, well below the district average of 32.9%. Fundraising disparities can even be traced back to redlining of Portland neighborhoods: Most notably, the top earner from 2021/22, Duniway, resides and draws students almost exclusively from a “greenlined” area in a 1938 redlining map, a designation that excluded people of color on the basis that the neighborhood had a high concentration of homogenous, white, higher-income families. In addition, other top eight super-earners, such as Ainsworth, Rieke, and Laurelhurst also draw the majority of their students from zones designated as “best” or “still desirable,” while these areas only make up 35% of the city in the 1938 map. “Our residential patterns in Portland housing patterns are very much racialized. That plays out because you’ve got a concentration of parents in higher income areas that have way more generational wealth than people in my neighborhood do,” said DePass, “and [they] have the ability to raise tens and thousands more dollars than in schools in my zone, for instance.”

Testimony from Roosevelt and McDaniel parents in a June 2022 PPS-organized roundtable on foundations raised another issue: districtwide community. The stated belief among parents was that “the current system is perceived to create ‘silos’ and ‘hoarding’ at a school-level,” according to a district-administered survey report. Parents also showed increased interest in a “collective impact model,” or a district-wide funding model that moves away from individualized fundraising. “As long as we continue to encourage or allow Parent Groups to fundraise large sums to solely benefit their own school we will continue to see the divisive nature of fundraising in PPS. Instead of school-based fundraising the district should foster and facilitate a spirit of community,” read a summary of takeaways from the roundtable.

Pro-foundation supporters have pushed back against the collective impact model, arguing that it would result in affluent parents disengaging from fundraising. A concern raised by Save PPS Foundations cites that creating a district-wide fund may reduce funding, as “many donors will simply not donate if at least a portion of their funds aren’t contributing directly to their own students/school,” or that it could lead “donors to mov[e] to private schools.” Cavanaugh responded by saying, “I think that’s kind of insulting to the PPS parent community … saying if I don’t see it going directly to my kids I’m going to take my ball and go home; it makes me sad if that’s really a pervasive sentiment, because I see my kids as part of a broader community.”

While the board is committed to aligning foundations with community, equity, and racial justice goals, reforms are not guaranteed; based on attitudes in the most recent foundation worksession, Board Members Julia Brim-Edwards, Scott, and DePass may be interested in ending the practice of local school foundations, while Lowery and Amy Kohnstan appear to want to continue foundations. That leaves two potential swing votes, Gary Hollands and Herman Greene, who may inform the future of private fundraising in schools. “Right now, everything is on the table,” said Hollands. Lowery believes the policy committee will propose a plan to the full board, representative of community perspectives, by March.

Even if foundation policy was changed, inequitable fundraising may still persist. “If we were to do away with foundations, we would still have PTA and potentially boosters,” said Walker of Friends of Lincoln. “Both those organizations do not have equity mechanisms,” she added. While boosters and PTA organizations can’t fund additional staff, they are able to contribute disproportionate amounts of money to other activities. These fundraising mechanisms are less visible and generally receive less scrutiny. Some worry that reforming foundations may lead to schools diverting their fundraising to these entities. “I’ve always said from the beginning that we need to look at school-based fundraising as a whole,” said Lowery.

At Lincoln, private fundraising supports the music program, athletic department, and students struggling with food insecurity. According to Walker, the Friends of Lincoln Foundation recently helped students find housing over the holidays. “I support foundations because I’ve seen the good they can do in schools, and I also fully understand where the reform folks are coming from and [I] appreciate their position,” said Lowery.

Board members hope to strike a balance that can retain the beneficial parts of fundraising while making it more equitable. “I am not anti-fundraising. I think we should encourage people to raise funds,” said DePass. “I think my question is whether we can craft a system that results in more equitable distribution,” she wondered.

Despite their opposing viewpoints, all sides agree that foundations shouldn’t need to exist in order for students to receive the resources they deserve. “We need a public school system and a system that shouldn’t rely on philanthropy, because philanthropy is at the whim of those giving,” said PAT President Bonilla. Cavanaugh and Bonilla have both floated alternative ideas for fundraising including after school programs, a housing assistance fund for students struggling with displacement, or even lobbying trips to the state capital to work towards an increase in public school funding for all. Both sides, in coordination with the board, are working together towards a solution that appeases all parties. “It’s about trying together to find the best path, and no one person’s idea is sufficient for the whole community,” said Lowery.

Leah J. • Jan 25, 2023 at 10:09 am

Great balanced article. Thank you.