Content Warning: This article contains descriptions of extreme weight loss and methods associated with weight loss. It also includes mentions of disordered eating that could trigger readers.

What do trash bags, laxatives, and exercise bikes have in common? They’re all methods for high school wrestlers to cut down to a lower weight class as quickly as possible. Some high schoolers drop as many as thirty pounds off their day-to-day weight in less than a week in an effort to achieve wrestling success.

Wrestling is an individual sport where athletes compete in 1 v. 1 matches. The goal is to “pin,” or put your opponent’s shoulders on the mat. Matchups are divided into weight classes, which are ranges of weights. Athletes compete against wrestlers in the same weight class in order for the matches to be more balanced. To participate, wrestlers must weigh in before their match at or below the maximum weight for their class and above the next lowest class’ maximum. With limited spots in each weight class and the highly competitive nature of the sport, wrestlers often “cut” weight prior to “weigh-ins.” Weight cutting is a central part of the sport as the long-held narrative in the wrestling community is that the lighter a class you can compete in while still retaining muscle and size, the more of an advantage you’ll have. It is also a highly prevalent aspect of other combat sports including boxing and mixed martial arts.

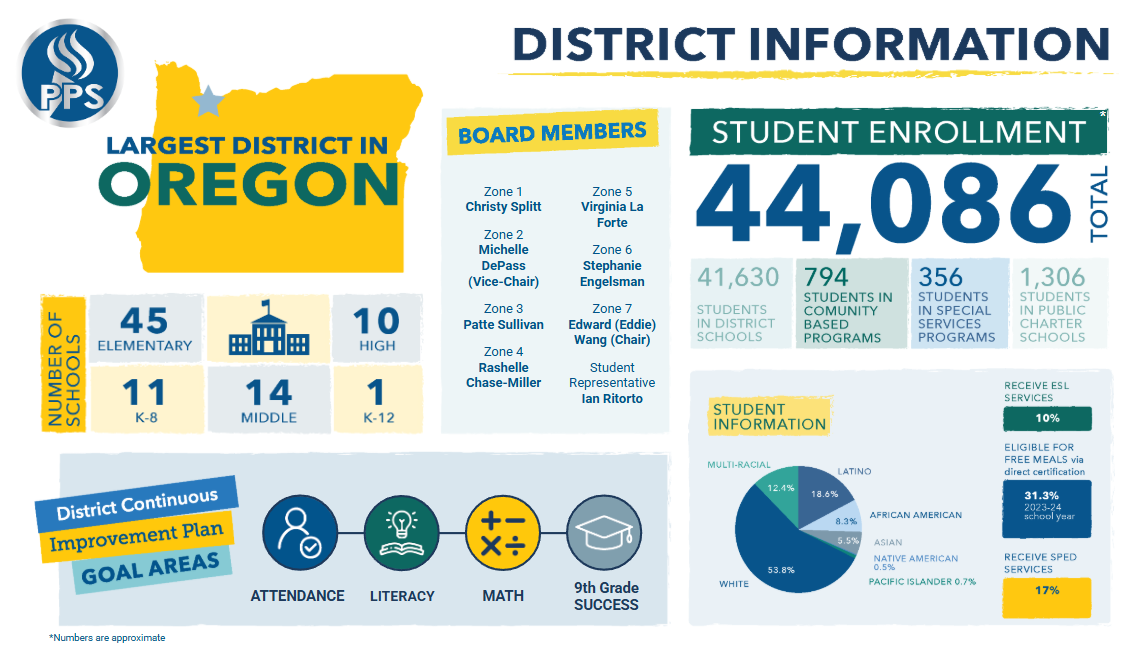

Currently in the Portland Interscholastic League (PIL) and Oregon School Activities Association (OSAA) if a wrestler aims to lose weight, coaches are meant to encourage them to do it through healthy exercise and eating. A lot is entrusted to the coaches, as the resources they provide about proper nutrition and exercise are mainly up to them. Coach Steve O’Neill says that at Franklin, they make an effort to talk to the team about nutrition and conscious dieting for competition.

The amount of weight athletes are expected to cut is also on a school-by-school basis, with some regulations in place. O’Neill states that; “At Franklin, we don’t push kids to cut a lot of weight. If they’re within one or two pounds I will ask him, but if a kid’s not comfortable … there is very little pressure.” He wants “kids to stay healthy and get bigger and stronger rather than cut weight and deplete all their energy.” He is not sure if the coaches at other PIL schools share the same sentiment.

He emphasizes that in the past, a lack of knowledge and regulations led to methods for cutting weight often being unhealthy. As a wrestler in high school, he would sometimes cut 15 pounds from Monday to be on-weight for a Thursday tournament. He describes his after-practice routine as eating a couple of boiled eggs, drinking some water, and then going to the club in full sweats. He would drag the exercise bike into the sauna, ride it for about an hour, and then go home. At his house, he would cut holes in a trash bag and wear it underneath his sweats while sleeping. These methods helped him to sweat pounds off.

The night before a tournament he would spend his time cooking. This food wouldn’t be consumed until the next evening, after he’d weighed in and made his weight class. Now, O’Neill, who also works as the culinary teacher at Franklin, finds cooking makes him lose his appetite. He adds that his “body image is shot,” expressing, “I know I’m not, but I look in the mirror and I see fat.” He compares the effects of weight-cutting to anorexia. O’Neill started cutting weight in seventh grade.

The disordered eating seen in weight cutting for wrestling is also similar to that of people with bulimia, a disease characterized by binging on food followed by periods of extreme food restriction. David Sherden, a certified athletic trainer and weight assessor for OSAA, highlights this as one of the major problems in wrestling. He describes how malnutrition from starving is followed by binging which then requires more starvation and dehydration from wrestlers if they want to make weight. If athletes are able to meet the weight requirements their performance will likely be impacted. Often they wrestle poorly due to exhaustion and dehydration.

Still, unhealthy weight loss strategies continue. Wrestlers at Franklin describe not eating or drinking until after weigh-ins on tournament days. Jaymi Iv, one of these wrestlers, also discusses wearing sweat suits while running to try to sweat all the water weight out. Some wrestlers will take laxatives if they are over their desired weight a few days before a big tournament. Iv states, “Wrestling is very hard on my body, and cutting weight is a big process of that … Cutting weight has made me always want to hop on a scale and check my weight.”

Gerilyn Armijo, Franklin’s current athletic trainer, elaborates on the physical impacts. Severe dehydration is a common side effect as a result of many athletes that try to cut water weight. This dehydration often leads to cramping. Low blood sugar from not eating is another prevalent issue. She recalls that athletes “get the ‘shakies’ and they feel like they’re going to throw up … or pass out.”

Even with knowledge about the adverse effects of cutting weight quickly, the practice persists. Oftentimes at tournaments schools can only enter one wrestler per weight class in the varsity division. If others are in the same class, athletes will have to wrestle JV. If they want a varsity spot, they may have to move a weight class. As Sherden puts it, “It wasn’t that [wrestlers] wanted to wrestle lighter. Just that where they weighed right now there’s a guy who was better, so they had to go up or go down.” He elaborates, “They go up, they’re facing bigger, stronger athletes so it’s more attractive to go down.” In an effort to mitigate this, the more popular weight ranges have been split into additional weight classes. Within PIL there are now 14 different weight classes ranging from 106 pounds to 285 pounds.

Another line of reasoning behind weight-cutting is strategy. If wrestlers cut down to a smaller weight class, but size and strength-wise they stay larger, they will have a tactical advantage. According to OSAAToday, Jeremiah Wachsmuth, the 2022 106-pound division USA Wrestling Cadet National Championship Greco-Roman winner, attributes his win to a switch in weight classes. He previously wrestled in the 113-pound bracket but made the decision to cut after talking to his coaches.

While it may have worked in Wachsmuth’s favor, this is not always the case as it is usually a temporary solution. Sherden recalls a former Franklin wrestler who made extreme cuts during the season and won his weight class at the district tournament. Yet, he says that “after his last weigh-in he kind of went a little nuts and he … ate and drank a lot of fluid.” The following Thursday the wrestler needed to weigh in at the state tournament. Sherden continues, “He just couldn’t get there. He tried … He was up all night … Sweating and sweating till he was half delirious. He was exhausted … could barely function and still had a couple of pounds to go when the bus was leaving. So he didn’t get on the bus.” When you don’t make weight, your team loses a team point. As the athlete was in a lighter class, his weigh-in was earlier and that year he was the first state tournament participant that didn’t make weight. Sherden recounts, “Up on the scoreboard … before the tournament, everybody else had zero points and Franklin had minus one.”

Even when wrestlers make their desired weight division, the cutting can weaken them. Geoffrey Baum, a NCAA champion wrestler, told Sherden that he liked eating a steak the night before tournaments. He credited his success to this because he “had a steak in [his] belly and the other guy was starving.” O’Neill highlighted the importance of properly fueling your body as well. So did Sherden, stating, “Sometimes the lowest weight is not the optimal weight. There’s a weight where you’re at your best … Don’t always seek out the lowest weight. Seek out the best weight.”

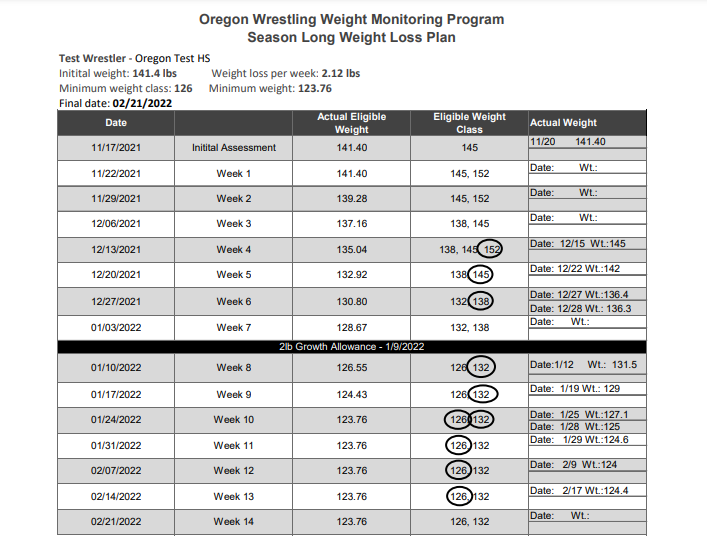

In 1991, the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association pioneered a weight control program to try to help with this. As of 2005, OSAA has adopted the regulations. The Oregon Wrestling Weight Monitoring Program requires wrestlers to be assessed by an OSAA-certified assessor. Wrestlers are given a hydration test in the form of a urine sample. This is to check that they are not using unhealthy dehydration methods to lose weight. If they pass, their height and weight will be measured. The assessor then uses a Bioelectrical Impedance Assessment (BIA) to find the athlete’s body fat percentage. BIAs measures this by sending an electrical current through the wrestler’s body and looking at the rate it travels. More fat will slow the current down. The minimum body fat percentage for high school males is 7% and 12% for high school females, unless the athlete can provide a signed physician’s note stating that they are usually under that body fat percentage. Sherden would like the 12% for women to be raised as he thinks it’s a bit too low. The wrestlers must be measured in a legal competition uniform.

Assessors input this data into a computer program (TrackWrestling) which generates a season-long weight loss plan for the athlete. They are provided with the amount of weight they can lose each week through weekly minimum weights. On average the weekly weight loss limit is 1.5% of body weight. The program also decides which two weight classes the wrestler is eligible for that week. In January, wrestlers are given a 2-pound growth allowance and each weight class goes up by two pounds.

In the past, wrestlers would only have to get a doctor to sign off on their minimum weight. There was a lack of supervision. O’Neill recounts, “It wasn’t safe and it wasn’t regulated.”

While safety measures for high school wrestling have steadily improved, a majority of it comes down to student choice. O’Neill says that “it’s pretty much self-regulated outside of practice.” Limits on the lowest weight class an athlete can compete in may reduce the amount of weight cut, but cannot do anything in regards to the methods used. While the week-by-week weight loss plan created by the program is provided, it’s up to a wrestler to decide if they will follow it.

Many wrestlers find that as they reach the day of the competition they are so close to the maximum weight for their division that they will not eat or drink until after they weigh in. Coaches have no real way to supervise this. They are aware of it, however. Weigh-ins are typically an hour before matches so that kids can eat and hydrate before the competition.

However, initiatives to start doing “mat-side weigh-ins,” have begun gaining traction. Mat-side weigh-ins would have each wrestler weigh in right before their match starts. The hope is that athletes would stop spending competition days cutting and would instead have to be on-weight all the time. Sherden is in favor of at least trying it and hopes to see a couple of districts pilot the program. He’d like to see how it changes the decisions of coaches and wrestlers about weight classes and cutting. He does contend that while the coaches in favor think it would keep wrestlers more honest, the majority are opposed. He cites the insecurity around potentially forfeiting more matches due to not making weight as a main reason for the strong opposition.

In addition, Armijo brings up the fact that it might further exacerbate unhealthy habits as wrestlers would have more time to cut weight with less time to recover. Iv agrees as having the hour between weighing in and your match to eat removes stress. She explains that, “If you have to go through a full day without eating or drinking because you’re worried your weight will fluctuate, then by the time you wrestle you aren’t in a very great mood.”

Iv instead advocates for daily weight checks. By monitoring wrestlers’ weights at practice, coaches can see if they’re cutting unhealthily. She specifically emphasizes weigh-ins before and after practice so that coaches can check that athletes are hydrating properly. O’Neill says that at Franklin they check their weights every day. Sherden also supports more frequent weigh-ins as he believes it can help athletes be more consistent with their weight.

The major role weight loss plays in wrestling calls into question the long-lasting impacts extreme weight cutting can have. By restricting calories and nutrients vital to growth, athletes may stunt their body’s growth. Mentally, they describe serious problems stemming from cutting. Yet right now there is no way to separate the sport from the focus on weight due to the organizational nature of it.

Wrestling provides a team environment for students, with O’Neill saying, “These kids, they’re family.” Still, despite the support they may receive, athletes struggle. The mental toll of weight cutting can lessen their enjoyment.

Currently, the question is: How can we continue this much-loved sport in a way that reduces the pressure to cut weight? O’Neill states, “I want kids to have a great experience with wrestling. I did too, but it probably would have been better if I didn’t do that [extreme weight cutting] to my body.”