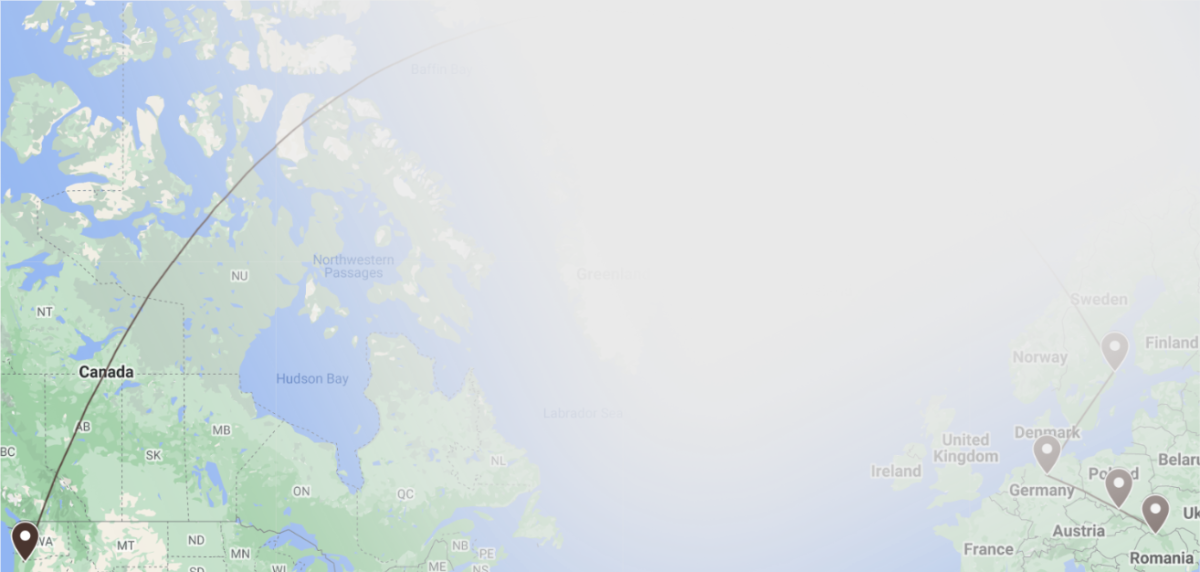

Blurred map of Holocaust survivor Alice Kern’s journey of movement during and after the Holocaust. As the generation who survived the Holocaust continues to age, these experiences are being lost.

Year after year, the experiences of Holocaust survivors are lost. With record-breaking rates of antisemitism reported by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), preserving these experiences becomes increasingly vital. As the generation which survived the Holocaust continues to age, these experiences become less accessible to newer generations. The loss of Holocaust experiences often leads to youth not understanding the gravity of antisemitism. At Franklin High School (FHS), students are witness to and sometimes participate in antisemitic acts. On social media, where celebrities like Kanye West are tweeting antisemitic messages, to students drawing swastikas on bathroom stalls, education and empathy around the Holocaust are lacking within this generation. In 2021, a total of 2,717 incidents of antisemitic assault, harassment, and vandalism were reported to ADL. Preserving and expressing interest in the experiences of survivors is ever so important to help fight the rise in antisemitism.

Debbi Montrose, the daughter of Holocaust survivors Alice and Hugo Kern, shares her mother’s Holocaust experience through educational outreach with the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education as a way to preserve her story. Alice Kern, formerly Alicia Luci Koppel, was raised in Sighet, Romania, and had a childhood like anyone else. During her teenage years, she flirted with boys and did normal teenage things until March 1944, when Nazis invaded Hungary. The town of Sighet fell under the direct control of the Nazis and their policies.

At the age of 21, Kern was transported by foot and cattle car; separated from her mother and cousins; and sent to a cement building within their destination, Auschwitz-Birkenau. A soldier told everyone in the line to go either left or right. Kern was told to go to the right, but her mom and cousins were going to the left. When she tried to follow them, the soldier pointed a gun at her, saying she needed to go to the right. This was the last time they would ever see each other.

Day after day, she worked physically demanding jobs from sunrise to sunset, would line up for routine counts, was threatened to be sent to the crematorium, was given little food, and was stripped of her identity as Alice and replaced with a number—A-7903. This continued until January 1945 when Nazis were close to losing the war and decided to evacuate all the people from Auschwitz to factories in Germany. After marching for days, she was put back on a cattle car and was transported to Bergen-Belsen, another concentration camp, where she contracted typhoid fever. She nearly died from the disease, but in April of 1945, she woke up to a soldier speaking English—they had been liberated.

That summer, Kern traveled to Sweden, where she stayed in a converted hospital and began to regain physical and emotional strength. She met her husband, Hugo Kern there, and by December 1946, they were married. Two years later, they immigrated to the US, sponsored by a Longview, Washington resident, and settled down in Portland, Oregon, eventually having Montrose and three other daughters.

Montrose explains that growing up, her mother never talked about the Holocaust or her experiences during it. This meant that Montrose and her siblings didn’t know what their mom had been through. “She scribbled on papers all throughout our childhood, we never knew what she was writing. She would stay in the car when she took us to places, just scribbling and writing,” describes Montrose.

Later on, once she was an adult, Montrose recounts when she went and watched her mother speak at a school. Her mother explained that she had heard on a talk show when she was learning English that if you have something on your mind, you should write it down. Kern would typically hide her writing when she wasn’t working on it. She didn’t talk about her experiences until “one time she was sitting next to a minister who saw her tattoo and he asked if she could tell him what life was like in the concentration camps. She said she didn’t know if she could do that, but that she had written it all down,” says Montrose.

She adds that “there is something called crisis shock and it takes about 50 years after a major incident before people can internalize the meaning of it.” Montrose shares that while it was hard for Kern to talk about her experiences from the Holocaust, “she found that once the students asked, she could just tell. Otherwise, she wouldn’t say a word about it … Anyone who wanted to know, she would tell.”

While these experiences are slowly disappearing, they’re not gone yet. Videos, books, and history lessons surrounding the Holocaust will remain, but as Owen Pollack, FHS’ Jewish Student Union president explains, “having someone directly speak to you about what they went through is much more powerful. It allows you to realize that what you might have heard or read about actually happened to the person standing right in front of you.” With antisemitism all around us, and increasingly visible in younger generations, remembering and sharing the experiences of Holocaust survivors continues to be extremely important. Pollack explains that “by educating new generations about the Holocaust, we can allow the [experiences] to be preserved even as the last of the survivors pass on, so that people can continue learning from the mistakes of those before them, and hopefully create a more inclusive and less hateful society.”