In the past few decades, with the rise of the Internet, many people have also perceived a rise in the rate of conspiracy theory beliefs. According to a study published in 2022 by the journal PLOS One titled “Have beliefs in conspiracy theories increased over time?”, 73% of Americans believe that conspiracy theories are currently “out of control,” with approximately 77% attributing this to the Internet. More than ever before, understanding the psychology behind these theories is of the utmost importance, and a variety of factors contribute to believing in conspiracy theories, from a desire for a sense of community to wanting to better understand the world around the theorist.

University of Oregon doctoral candidate Cameron Kay provided two definitions for conspiracy theories. The first is a simpler one that shows an element of harm: “It combines three things: a powerful person or group, who is using deceitful or shadowy means, to benefit themselves or harm the public.” The second one is a more in-depth definition: “An unanswered question—if it’s answered it can’t be a conspiracy theory—it assumes nothing is as it seems, it portrays the conspirators as preternaturally competent and as unusually evil, [and] it is also founded on anomaly hunting and it is ultimately irrefutable,” says Kay. The theory is irrefutable specifically in the mind of the conspiracy theorist. Kay continues, “So for example, if you present evidence to the contrary, a core feature, maybe not a necessary feature, but a core feature, many conspiracy theorists will be able to come up with an excuse for why your evidence does not hold.” This definition is taken from Rob Brotherton, in his book “Suspicious Minds,” which is a great resource for learning about this topic further.

There are thousands of conspiracy theories out there, and without a method of organizing them, the life of a psychologist trying to understand these theories would be much worse. Luckily, there are many different ways to classify the thousands of theories out there. A study from 2013 by Rob Brotherton published in the journal “Frontiers in Psychology,” called “Measuring Belief In Conspiracy Theories: The Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale,” took 100 different theories and analyzed the differences and similarities between five different categories.

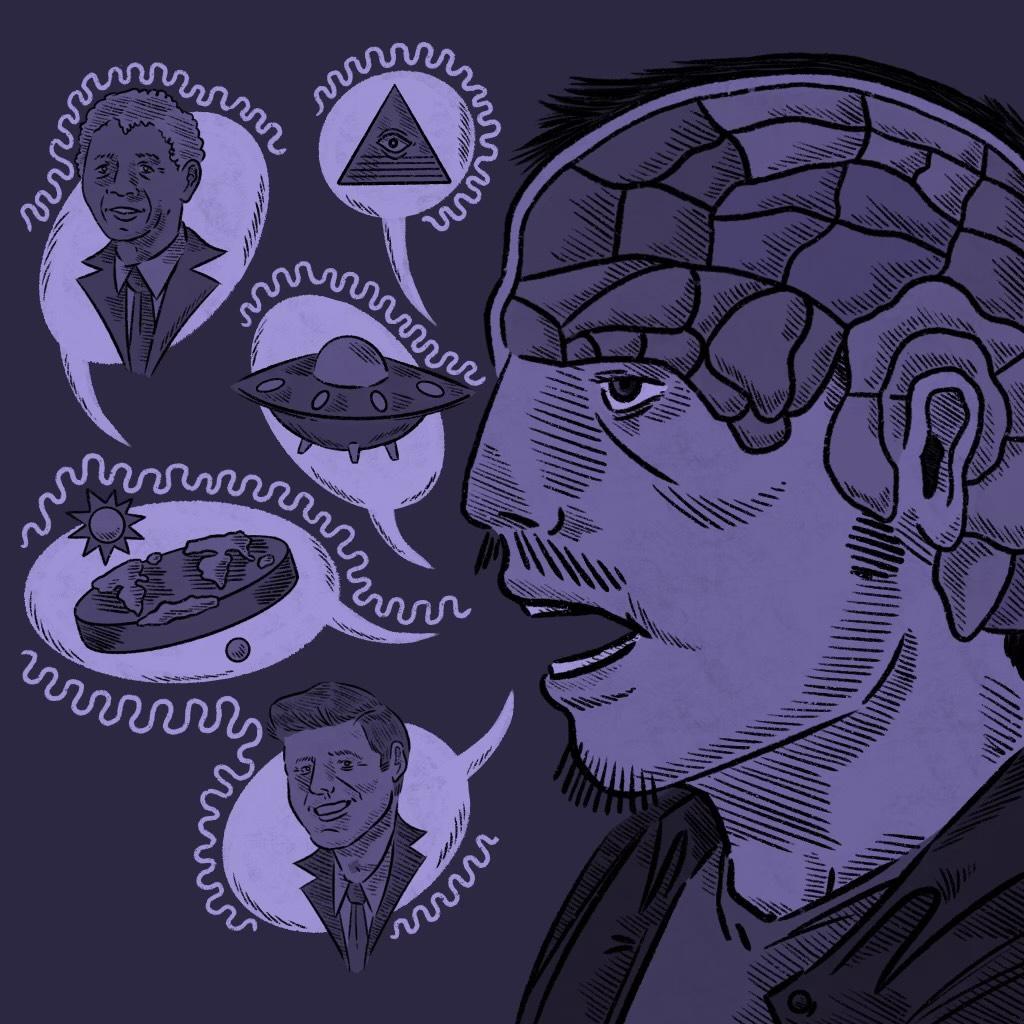

The first type, government malfeasance conspiracy theories, suggest that “the government is up to no good,” according to Kay. The second type is extraterrestrial theories, an example provided by Kay being “aliens in area 51.” Thirdly are malevolent global conspiracy theories. For example, the Illuminati theories, as Kay puts it, are the idea that “there are these powerful groups of people that control everything.” Fourthly there are personal well-being conspiracy theories—for example, “think about a lot of the COVID-19 conspiracy theories, that it [were] ‘designed by some actor or some organization to potentially control the population’ or do something else nefarious.” says Kay. Finally, there are control of information theories. Kay says that these can focus on, “groups of scientists who manipulate and fabricate data, for example.” An example being Flat Earth theories. However, with varying branches within individual theories, a conspiracy can fit in multiple categories. Based on data from a sample of undergraduate students at the University of Oregon, control of information and government malfeasance theories are the most popular types.

How these theories develop, and how people come to believe in them, is another critical part of understanding the full picture. One such motive is the proportionality bias: “Something had a big impact, therefore … it had to be the result of a lot of planning and a lot of resources to make it happen,” describes Franklin High School AP Psychology teacher Greg Garcia. An example of this bias is shown in the Abraham Lincoln assassination. “It was the first time a [US] president had been killed. Major effect. So there must have been major causes,” says Garcia.

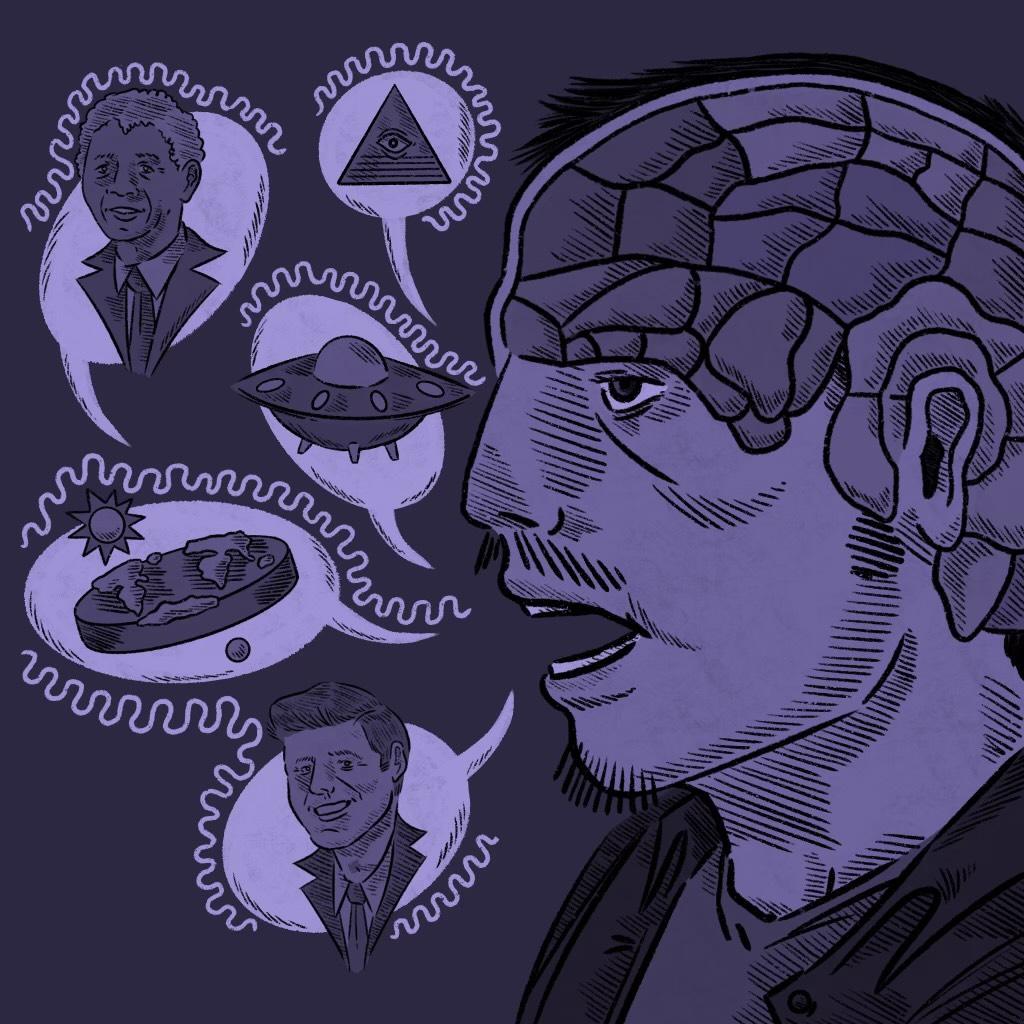

There are three main motives behind the development and belief of these theories. Epistemic motives are one explanation. These motives revolve around understanding one’s environment. “People have a desire to figure out what’s going on around them … So if things are kind of up in the air and people don’t know what’s going on, conspiracy theories can really fill that void,” says Kay.

The second motive is the existential motive, which is the desire to feel safe in one’s environment. “One reason people tend to believe in conspiracy theories is they think, ‘Okay, I know what’s going on. Before I believed in conspiracy theories, I didn’t know what was going on, there was all this manipulation going around me [with] people getting up to their no good, [and] by discovering this conspiracy theory I am back in control.’ Unfortunately that seems to often backfire,” explains Kay.

The third motive is the social motive. “It’s about maintaining a positive image of the self and the social group,” says Kay. The thought process of a person driven by this motive, Kay explains, often looks like this: “‘I’m in possession of some knowledge other people don’t know, I’m special because I know this thing.’” All three of these motives were outlined in a 2017 study by Karen Douglas and her team published by the Association for Psychological Science and titled “The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories.”

Another key aspect of why people follow these theories is conformity. This conformity is fully displayed in the Solomon-Asch conformity experiment, in which a group of people, one being the test subject and the rest being in on the experiment, were asked to look at a piece of paper with different lengthened bars on it. Their job was to say which one of the bars matched the sample bar that was also shown to them. The right answer was obvious, but the people who were in on the experiment intentionally gave the wrong answer. By the time it got to the test subject, the results were very telling. “There’s a one in three chance that the actual test subject is going to say the wrong thing,” says Garcia. Garcia explains further the effects of this concept in a real-world situation: “If you live in a place where the political angle is such, where the political bias is strong, one way or another, it’s very similar to the Solomon-Asch [experiment].”

There is one main notable benefit to conspiracy theories. They can often provide a sense of community, creating groups of people who “believe” in these theories simply because it provides a social circle, and a common topic to discuss. “Presumably it does provide this sense of belonging,” says Kay. However, belief in conspiracy theories does lead to rejection of scientific evidence in a few topics, including “distrust of vaccines [and] distrust of climate change. People who believe in conspiracy theories are less likely to trust vaccines,” states Kay. The development of prejudicial ideals due to conspiracy theories is also very real. “You see that conspiracy theories are associated with islamophobia and antisemitism,” says Kay. Conspiracy theories also have been shown to lead to other racist beliefs, according to Kay: “[It’s] associated with anti-Chinese prejudice during the Covid-19 pandemic.” It also leads to political apathy, causing a lack of trust in voting.

According to Kay, one thing is crucial in understanding conspiracy theories: Going after individual theories and people will get us nowhere in combating the harms of conspiracy theories. Instead, Kay urges people to do two things. First, try to provide a sense of community to those yearning for it, but with a less harmful social group. If they can get that sense of belonging somewhere else, Kay believes they might not have to turn to conspiracy theories. The second step is most important, as he believes that, “the big thing is cutting down on misinformation. If these theories aren’t out there, and they aren’t being shared, if you’re not exposed to them, well then you can’t pull them in and use them to address these motives.”