I met with Jessica at the American Medical Response (AMR) building on SE 2nd and Ankeny. She holds her toddler, Peyton, in a sling on her shoulder. Jessica greets me warmly and leads me inside the large gray concrete building. This particular AMR facility lies directly underneath the Burnside Bridge: “we get stuff falling [from the bridge] onto our cars in the parking lot all the time,” says Jessica.

Past the double-door entrance, a warehouse holds upwards of 40 ambulances lined against the walls, leaving a wide path leading to the exit bay door at the back of the building. Jessica has a wealth of knowledge and experience from over 10 years working as an EMT. She points out every detail within visibility. We pass by a large shipment of medical equipment stacked in cardboard boxes, and a storage room with countless pieces of highly technical equipment.

“So this is an ambulance up close,” Jessica says while opening a door and hoisting Peyton in her arm. All of Jessica’s motions— showing me the ways things worked, from disassembling and reassembling pieces of equipment to interacting with the ambulance itself, are practiced and meticulous. She swings open the side door and lifts Payton inside the ambulance.

Inside the back of the ambulance is a cramped space. Two people can sit comfortably, but adding a third in the form of a patient while moving at high speeds in a crowded city seems unimaginably difficult. A small waist-high bench runs the length of the interior left wall. On the adjacent wall is the medicine and drug storage. Needles and small vials sit behind clear plastic cabinets in styrofoam holders. Jessica points to a rack near the front of the vehicle and says, “that is our LUCAS device. It’s a life saver.” The Lund University Cardiopulmonary Assist System (commonly called the LUCAS Device) is a new piece of technology that initiates CPR automatically for patients in cardiac arrest.

The ambulance stores an enormous amount of tools and technology. From an outside perspective, it’s almost impossible to understand the amount of knowledge and information that an EMT or paramedic has to remember. Jessica takes me inside the breakroom and I take a seat at the circular breakroom table across from Marty. Marty is a paramedic. “I’ve been working here longer than you’ve been alive,” (about 30 years) he tells me. “This is a very, very tough [industry].”

Marty points to a woman who has just woken up from the couch in the corner of the breakroom: “She just got off a 24 hour shift. 24 hours in a row.” The schedule of medical responders is four days on, and four days off. Marty says, “sometimes we’ll pick someone up who is violent. And this is after eight hours with no bathroom break or time to eat.” Jessica enters back into the room and takes a seat at the table with us. Marty goes on to tell me about the “rock thrower”: “We have one guy that is always around [this area] that throws rocks at us.” The woman and Jessica both smile and nod slowly as he says this. “Not pebbles, either. They’re big rocks. He’s caused tens of thousands of dollars in damage. He’s broken a windshield,” Marty continues.

Medics slowly begin trickling into the breakroom and connected office. Marty stands up and explains, “sorry, I have to do this sometimes. I have a bad hip.” Jessica interjects, saying “oh yeah, tell him about that.” Marty elaborates, “I had this call where I had entered this very small room with one light. The light went out and I was attacked. I had to wrestle this person to the ground which injured my hip pretty [badly]. I [have had] to get surgery on my hip [multiple times] because of that incident.”

Marty told me another story about what caused his injury to be reignited: “We had just picked up this guy. He seemed completely normal for about five minutes. My partner and I had him on the stretcher and out of nowhere jumped up and pinned my partner’s neck against the wall [of the ambulance] with his forearm.” He continued to tell me how “it took the two of us to get him in a headlock on the ground while we waited for the cops. Luckily my partner was a young guy, otherwise we wouldn’t have been able to get him to the ground… Meth is one hell of a drug.”

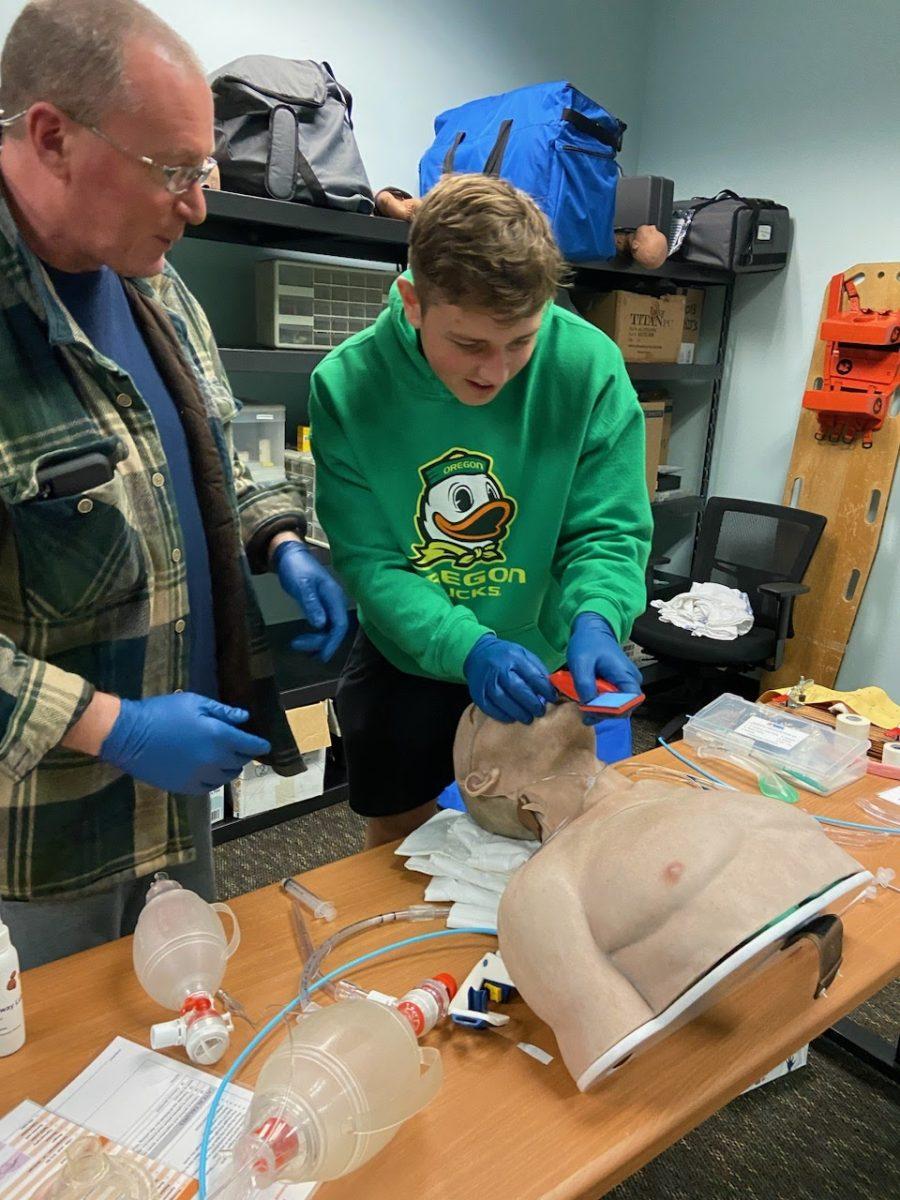

Marty and the other paramedics told me of many other incidents like this one, with grinning indifference, as if they hadn’t just explained how they delivered a baby in the back of a moving ambulance or saved hikers lost in the vast wilderness of Eastern Oregon (both true stories). I was brought into the main office of the AMR facility and was shown the dispatching and scheduling screens and tools. I was taught how to intubate a dummy, and how to drill into someone’s bone marrow to deliver drugs if an IV is not viable. Marty showed me how to administer pain medication to infants and toddlers in varying states of turmoil. However, during our conversation, I felt completely comfortable with this group of people I had never met before. They were understanding, focused, and empathetic. A quality that, as Marty puts it, “gets more and more difficult to come by.”