For many, the name Warhol likely brings to mind some disco-centric amalgamation of soup cans and Jackie Kennedys. However, when it comes to the artist’s personal life, the details are (much like his work) up for interpretation. What were his inspirations, his motivations, his loves and lovers—and why Campbell’s? A new Netflix six-part docuseries based on the published diaries of Andy Warhol, aptly titled “The Andy Warhol Diaries,” pulls back the curtain on the painter who defined contemporary culture as we know it.

Much of the series takes place in Warhol’s post-Factory period—after he was infamously shot, technically dead—in the 70s and 80s. With dozens of interviews from Warhol’s personal friends, art critics, and the twin brothers of his former lovers, we’re taken from Warhol’s impoverished childhood in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to the tolls of fame and success; from waning public interest and shifting generational attitudes, to devastating loss, it is all narrated by the AI-generated voice of the artist himself.

In 1949, Andy Warhol (born Andrew Warhola), in the storied fashion of future stars, arrived in New York with $50 and little else to his name. He began his career in advertising, illustrating shoes for fashion magazines, but his breakthrough came with his iconic prints of Campbell’s soup cans. In the 60’s, Warhol and his famed art studio, the Factory, became the center of New York’s underground culture; alongside his popular screen prints of twentieth century icons, he produced theater and music (most famously “The Velvet Underground”), and directed several risqué experimental films: movies like “Couch,” “Kiss,” and perhaps his most well-known, “Chelsea Girls.” Many of these featured queer actors and relationships.

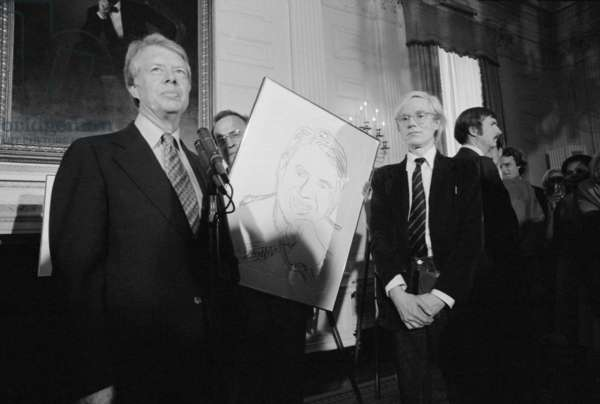

“[The] Factory represented all that was magical and interesting and exciting in New York,” attests Mark Balet, the creative director of Warhol’s “Interview” magazine. But the scene would never be the same after Warhol was shot and critically wounded by Valerie Solanas; a regular at the Factory, notable for her authorship of S.C.U.M. (or the Society for Cutting Up Men) manifesto—this event was later adapted for the 1996 cult-film “I shot Andy Warhol,” which I would highly recommend to anyone equally fascinated by Solanas. Warhol’s near death experience would spark a major shift from his utopia of misfits at the Factory to a new era of what he called “business art”: commissioned portraits, “Interview” magazine, and a return to advertising. It also marked the beginning of his relationship with Pat Hackette: “[In] 1976, Andy and I started a routine of talking to each other on the phone to keep a diary.” She would later publish these diaries, forming the basis for the docuseries.

The Diaries reveal a strikingly vulnerable side of Warhol that is rarely seen, and it’s fascinating to hear. Despite his witty, “above-it-all” public persona, never without the company of celebrity or wealth, his entries present an inherent loneliness and self-loathing; and not without reason. Although Warhol is held on a pedestal of excellence today, his work (and his existence) were underappreciated by many during his lifetime: “[He was] not at all accepted by the art establishment,” remarked renowned art dealer Jeffrey Dietch. “[They] thought he wasn’t passing effectively as a gay man in the art world.” The question of Warhol’s sexuality has always been disputed, as the artist never formally came out, instead preferring to spread the rumor that he was asexual. Yet Warhol was still associated with being gay; “He represented gayness,” author and culture critic Lucy Sante explains. “He was like the little picture in the dictionary for a lot of Americans who didn’t know.” Although Warhol didn’t come out as gay, he had several long-lasting, private relationships with men over the course of his career (namely Jed Johnson and Jon Gould). Nods to homosexuality, whether to his own sexuality or not, are prevalent in both his films and his artwork. His portraits of nude men and possible references to the AIDS epidemic in his “Last Supper” series all tie back to the conflicts Warhol had with his own identity, both in the face of general public opinion at the time and his Catholic upbringing.

Warhol also struggled with the constant battle of relevancy; with a career spanning generations, Warhol pivoted from era to era, adapting to magazines and then television. When graffiti artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat established themselves in the world of high art, Warhol established himself with graffiti artists. His work with Basquiat, although overshadowed at the time by overt double standards (one critic described Basquiat, a Black Haitian Puerto Rican, as Warhol’s “mascot”), remains a powerful collaboration between two of the most influential artists of the twentieth century.

Eventually, Warhol’s work was recognized for its influence on art and American culture as a whole, although primarily after his passing in 1987. Today, Andy Warhol’s pop-art is discussed in schools alongside Da Vinci and Picasso; I remember tracing a soup can in my first grade art class, although we weren’t told anything about Valerie Solanas. Franklin High School’s intermediate art class recently completed a pop-art assignment of their own, inspired by the art of Liechtenstein, Oldenburg, and of course, Warhol: “[The assignment] consists of making an art piece that has to do with contemporary culture,” explains Srule Brachman, an art teacher at Franklin High School. “Andy Warhol was very famous for taking Campbell’s Soup cans and Brillo boxes and turning them into art. Roy Lichtenstein would take comic books, and turn those into large paintings…” Students were encouraged to draw inspiration from these artists, capturing the mundane and creating something bigger (in physical size and in significance).

Interestingly, Brachman admits that he originally didn’t care for Warhol’s work. “When I was in college, I didn’t like his work because I’m an abstract painter,” he says, explaining that the arrival of pop-art, being so literal, posed a threat to the future of abstract art. “So, I didn’t really appreciate his stuff until I got older.” Warhol’s work is often dismissed for its literalness, and the opinion that they have no profound meaning. When asked about the meaning of his work, Warhol wasn’t quick to squash that belief; according to him, he just likes Campbell’s soup. “I think you can read any commentary into it; its social significance, it’s political or whatever,” Brachman remarks. “Or you can just look at it at face value and say, ‘I liked that image.’” However, while the soup cans and Chairman Maos in rouge can be taken with whatever interpretation you please, it’s unquestionable that images such as those in the “Death and Disaster” series have some commentary on ourselves, if not on politics or society at large; his screen prints of an electric chair, gruesome car wrecks and stills from the assination of John F. Kennedy maintain relevance, and continue to resonate with people today. “He’s bringing stuff out that we look at in a newspaper and maybe not even think about,” Brachman remembers thinking after viewing Warhol’s prints at the Portland Art Museum. “He’s making a statement that ‘here it is, right in front of your face,’ rather than, ‘oh, you saw it in the paper, just flip the page.’”

Having watched “The Andy Warhol Diaries” himself, I asked Mr. Brachman if he thinks the series will help diminish the misconceptions surrounding Warhol; he says, “I think showing the depth of his life and depth of his work will.” The diary puts forth a perspective that is often unavailable, and therefore left out of the conversation: Warhol’s own. Not the robotic interviewee or the wig-wearing gay icon, but Warhol in his own words. His feelings of loneliness growing up, his conflicts with love and fantasy, his grip on relevancy, celebrity and whether or not the art can survive these factors, as told by the artist himself. Having the full picture of an artist not only helps us understand their work, but connect with it as well. The full picture of Warhol is certainly something anyone can identify with. As John Waters put it, “If a pimply faced boy from a very poor home in Pittsburgh can end up being the social dictator of New York Society in some ways, it’s hope for everybody.”