During the post-World War II era, the United States made an effort to prioritize the movement of as many cars as possible, at high speeds, in street design. Speed limits rose, and to compensate for the higher speeds, lanes were made wider and straighter. More and more lanes were added to many roads. Freeways were developed and cut through cities. When streets and roads became too congested, lanes were added, with the hope that this would facilitate the flow of traffic. However, all these policies ended up making roads louder, less safe, worse for the environment, more packed, and less efficient at moving people from one place to another. In cities, the only way to make roads better—for pedestrians, bikers, buses, and cars—is to make driving alternatives as convenient as possible.

The shift toward car-centric urban design devastated neighborhoods of color and only strengthened the income gap between white and black Americans. Urban freeways were built, and because some neighborhoods had to be damaged in the process, city designers all over the country consistently chose the places with more low-income residents and more people of color to bulldoze, rather than disturb whiter and wealthier neighborhoods.

Even today, freeway expansion has often put such neighborhoods in harm’s way. Harriet Tubman Middle School, a plurality-black school in Portland, is situated next to I5. Since its founding, the school has faced issues with noise and air pollution. In spite of this, funding was raised for the I5 Rose Quarter Project, which would expand the freeway. In December 2021, the city started to plan to move Tubman to the Albina District and continue with the freeway expansion. This forces Tubman’s students and families to move school buildings. In addition to displacing schools for communities of color, the move is unlikely to even reduce traffic congestion by a significant amount.

André Lightsey-Walker is the Policy Transformation Manager for The Street Trust, a nonprofit that seeks to improve streets in Portland. He is a fourth-generation Portlander and a person of color. His family moved to the city in the 1930s, when legal racial segregation still existed in Oregon, and they weren’t allowed to live in much of the city. Then, after World War II, the city built I5 in the “path of least resistance,” he says, or by bulldozing parts of neighborhoods with residents of color. “Originally, growing up, [my grandfather] was able to walk straight through the neighborhood to get to school,” says Lightsey-Walker. Then, during the postwar era, “there was the creation of this giant ditch, which became I5, which meant that the crossings for a little kid to get to school were significantly impacted.” Lightsey-Walker’s grandfather is one of millions of marginalized people whose lives were made worse by the construction of freeways through cities.

In the U.S., where cars rule the roads and where the optimization of driving routes is the top priority, people tend to feel that cars are the most convenient way to move around, even at rather short distances. According to data from the 2009 National Household Travel Survey, 20 percent of vehicle trips go less than two miles, and more than 40 percent of all trips last no more than three miles. Many of these tens of thousands of decisions to drive a short distance are rational and defensible, because throughout the United States and Canada, taking bikes or transit is the less-convenient option. These are, in most cases, routes that could easily be replaced by bikes and buses if those options were made convenient.

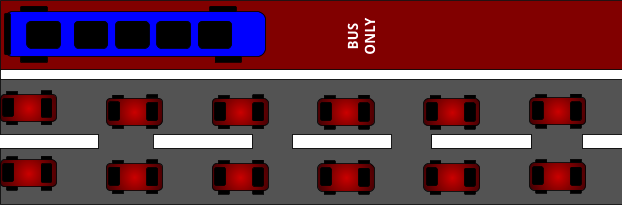

Cars and trucks are better at slowing each other down than any other mode of traffic, because for the number of people they move, cars take up an unreasonable amount of space. The average American car takes up nearly 90 square feet and moves 1.5 people, according to the University of Michigan. This makes moving large numbers of people by car less efficient than by other modes.

The model shown below is scaled based on the length of a typical Portland city block, which is 200 feet by 200 feet, per the city’s website. The two full lanes of cars would be predicted to move a combined 27 people. A single 40-person bus could exceed that load at even 70 percent capacity.

This issue of space is the biggest reason why so many American solutions to congestion backfire. Induced demand, in the context of streets, means that when roads are made more desirable to a certain mode of transportation, more people will take that mode. This is good for buses and trains, which can carry more people at once, and for bikes and sidewalks, which take more people out of cars. But when induced demand affects car use, it both makes the roads less safe and nullifies the congestion benefits of adding a lane in the first place.

In 2009, Gilles Duranton and Matthew A. Turner of the National Bureau of Economic Research found what they called “The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion”: As miles of lanes are added, demand is expected to rise by the exact same amount. This means that adding lanes to a freeway is expected to have no positive effect on congestion. It explains phenomena like the Katy Freeway in the Houston metro area, where repeated failures to reduce traffic have led to the development of a 26-lane thoroughfare, according to Business Insider.

However, even if cars were the best way to move people from Point A to Point B in the city, their use would still be difficult to justify.

Cars are estimated to have killed 42,060 people in 2020 alone, in the United States, according to the nonprofit National Safety Council, making it the most dangerous day-to-day task. Cars pose a threat to both their passengers and the people around them in a way no other mode of transportation can match.

The average American vehicle weighed more than 4,000 pounds in 2017, according to Forbes, and they regularly exceed 30 miles per hour in crowded cities, a recipe for disasters. No other vehicle can match this combination of speed and size with such a low economy of scale. This means that more cars need to be taken to carry the same number of people, increasing the number of deadly vehicles in a given area.

Today, the areas of Portland where crashes are most likely to occur are largely also those where residents tend to have the least money. According to the City of Portland’s Vision Zero website, an initiative devoted to improving street safety, 29 of the 30 most dangerous intersections in the city lie east of 82nd Avenue.

Owning a car is expensive. The average American spends nearly $10,000 per year on vehicles, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a ludicrous figure that many people with lower incomes cannot afford. Between insurance, gasoline, maintenance, repair, and other car expenses, they are not always a realistic financial option for people who live in cities. However, because most American cities are designed such that taking transit and cycling is much slower than driving, it can be a necessary expenditure for people in lower-income communities.

There are ways to move people more efficiently, more sustainably, and more safely than by car, and it is easy to do so within large cities. Even long-distance travel by car is replaceable if proper legislation is passed. In some cities, alternatives to cars have become the primary mode of travel for the majority of the population.

Bicycles are much smaller and slower than cars, and they don’t lead to heavy greenhouse gas emissions after being manufactured. While they can’t reach the same high speeds as cars, bicycles’ safety and size means that they don’t need to be regulated for safety as heavily, so a street can be packed with them without congestion issues or long stoppages. There are other major benefits to heavier use of cycling, as they are a form of active transportation and a source of exercise.

Unfortunately, even in Portland, bike infrastructure on many streets may be insufficient. Many projects involve little more than the development of painted bike lanes on the sides of the road, which are often unprotected from cars. “Paint isn’t infrastructure,” says Lightsey-Walker. “…In order to really protect people, we have to invest money or set up systems that actually protect them. Paint is not going to protect the car from hitting me on my bike, or [from hitting] pedestrians.”

The proximity to dangerous traffic makes bike lanes daunting to most cyclists, which reduces their ridership, and with so many people choosing not to take bikes, they can appear to be useless. Foster Road is a street in Southeast Portland that was recently renovated with driving lanes being replaced by bike lanes. Clay, an owner of Mt. Scott Fuel Co, a business along Foster that sells goods like firewood, was unhappy with the move. A few years later, he says the bike lanes are mostly empty. “We could sit out here together all afternoon,” he says, “and we’re not going to see a bike.”

The Street Trust and others have come up with alternatives to painted bike lanes. Lightsey-Walker recommends one simple solution: swapping the bike lanes with the parking lanes on streets. “Instead of using bike lanes to protect parked cars,” he says, “why don’t we start using parked cars to protect bikes?”

At their best, buses and other forms of public transit are able to move huge swaths of people at once without taking up much space. In Portland, though, the buses too often get stuck in traffic. This makes them unreliable and less convenient than cars, so most people don’t take the bus regularly, and in turn they are not able to provide as much value to a city as they could.

There are a few solutions to this. One is to add dedicated bus lanes throughout the city. These already exist downtown, and their inclusion elsewhere would allow buses to avoid traffic. Even the ones developed downtown make buses better for the rest of the city, says Hannah Schafer, a spokesperson for the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT). “Bus routes are on a circular kind of track,” she says, “and when they get stuck in one place in the system, that impacts the rest of the trip,” so any improvement helps everyone along any part of the route. Still, they continue to get stuck elsewhere, and this should be avoided. It takes space away from cars, but as has been established, buses are far more efficient at moving many people at once, so good bus lanes can reduce congestion in driving lanes.

Many city planners, especially those in progressive cities like Portland, support the idea of putting alternatives to cars first in street design. However, their projects are frequently met with resistance from the community and a strict budget. Metro, the system that runs TriMet, does get some federal funding, says Schafer, but PBOT doesn’t receive it unless through specific grants. “Typically that money is filtered through Metro or ODOT [Oregon Department of Transportation],” she says, and ODOT “share[s] it around to everyone in the state.” The Foster plan, despite being relatively modest, took years to be passed due to resistance from businesses along the street.

This is where the public comes in. Local governmental bodies like PBOT don’t receive much funding, so without public interest and investment in changes to Portland’s streetscape, such change is likely impossible. The car-centric postwar design of the United States was a system that oppressed people of color, made the most dangerous daily activity unavoidable, helped lead to climate change, and doesn’t move people efficiently. If Portland is to reverse this mistake, it needs the public’s help.