Last year in my English class, I read “There Is No Unmarked Woman” by Deborah Tannen. In this essay, she uses linguistics to explain how our society sees and judges men and women. Linguistically, unmarked is the standard for words, and marked refers to a word that has been altered. Her example is visit (unmarked) and visited (marked). In our society, essentially, Tannen argues that men are the standard no matter what choices they make, while everything women do is a choice, and every choice is judged. This essay is on my mind every time a female politician is idolized or demonized.

The problem with how we view female politicians is serious: instead of people, they are personas, representations of every woman in the country. Representation is important, but this standard seems to only apply to women. Male politicians are just politicians, not tasked with the enormous job of representing all men. This is incredibly unfair. If a man in Congress makes a mistake, it reflects badly on him, or at worst, on his party. If a woman slips up, it is used as a reason why women are unfit for politics. If this standard was applied to men, I could give you some pretty solid evidence as to why they should be excluded from political discussions (see the Kavanaugh hearing, the 2020 presidential debates, etc).

The Saturday Night Live skit entitled “Women of Congress” sums up this issue well. It features congresswomen portrayed like superheroes, complete with clever catchphrases and action movie background music. I thought it was funny, but it also perfectly illustrates this issue. We want female politicians to be larger than life, somehow more than regular people. We want to believe they are perfect women and that they can do literally anything. As a result, they face an astronomical amount of criticism, often more targeted than their male counterparts.

Male politicians are criticized for their words and ideas, which is valid. If you don’t agree with the people representing you in Congress, you have every right to let them know. On the other hand, female politicians are ridiculed not only for their political beliefs but also for their fashion, their age, their appearance, their children, their marital status, their religion. Every aspect of their lives is fair game. The same holds true for other marginalized identities in government. Their actions are taken to represent their entire demographic, and their actions are endlessly sensationalized. Remember the controversy when President Obama wore a tan suit?

Currently, there may be no more pertinent example of this disproportionate judgement and outrage than the criticism facing Amy Coney Barrett, the most recently-appointed justice of the Supreme Court. The most common complaint is that she’s not prepared for the role, and this concern is understandable. As Lilli Rudine (11) puts it, “she’s not even qualified and some of her ideas are scary.” This sentiment is not unique to Rudine. During her confirmation hearing, days after Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed away, Barrett refused to discuss a wide variety of important political issues, including climate change and the right to abortion. With her unwillingness to reveal her views on such pressing subjects, many Americans fear that she intends to take a strong stance against the expansion and protection of human rights in this country.

In that same hearing, Senator Ben Sasse asked Barrett if she could name the five freedoms protected by the First Amendment. She couldn’t. I was on Franklin’s constitutional law team at the time, and I was shocked. How could I know more about the First Amendment than an imminent Supreme Court justice? Then I realized how condescending the question was. That was the moment I realized I was caught between my disagreement with her fundamental beliefs and my dislike of the sexism she faced. I wonder if Sasse would have asked any other Supreme Court nominee that question.

While writing this article, I had to strongly examine my own thinking. I consider myself to be a feminist and aware of when sexism is present in any given situation, but I realized that I never referred to Justice Barrett by her title, and would instead call her Amy Coney Barrett. I never used the male justices’ full names, only their last names or titles. Subconsciously, I didn’t give her any respect, even before she had a chance to prove her ideals. I’m still definitely not a fan, and that’s hard for me to explain concisely, so I’ll borrow the words of an Instagram commenter: “Amy Coney Barrett is walking through all the doors RBG opened and shutting them behind her.” Justice Ginsburg was hailed as a champion of equality, and this public image was supported by her decisions while on the Court (ex: United States v. Virginia, 1996, which ensured women legally had equal access to education). One could argue that it is thanks to her that Barrett currently has a seat on the Court. On the other hand, many are concerned that Barrett will limit the rights of women across the country, particularly regarding abortion.

The combination of support for feminism and dislike of Justice Barrett has seemingly confused Trump supporters on social media. I can’t count how many times I’ve seen people accused of being anti-feminist simply because they don’t think Justice Barrett is the most qualified person for the job. In my experience, most of these accusations come from far-right Republicans and are directed at young liberal women. This argument is insulting. You can be a feminist and not like every single woman in the world. That’s just basic common sense. I bet the people who say this don’t like every man in the world, but that’s not stopping them. To be a feminist, you have to support equality (such as women being on the Supreme Court), but women are just people. You can agree or disagree with their opinions because they’re people just like everyone else.

For so long, women had no voice in politics, and even now the government is not equal. The first woman was elected to Congress in 1916, long after the country was established and still before women had the right to vote. Today, the Supreme Court is 67 percent male, and women make up only 27 percent of Congress. The country has never had a female president. And yet, this is pretty much as equal as the government has ever been in America’s history. I’m thrilled that women are gaining a stronger role in politics, but I’m excited for the day when a woman in a position of power isn’t something exciting or novel, but an everyday occurrence.

If you hate Justice Barrett, hate her for her opinions and how she might interpret the Constitution. Criticize her for her willingness to restrict bodily autonomy. Scoff in disbelief when she doesn’t know basic constitutional principles. But don’t mock her politics based on her outfit, family, or religion. Remember that her job is to objectively interpret the Constitution regardless of her personal beliefs. She deserves, at least, a chance. If and when she lets people down or abuses her power, that is the time for criticism.

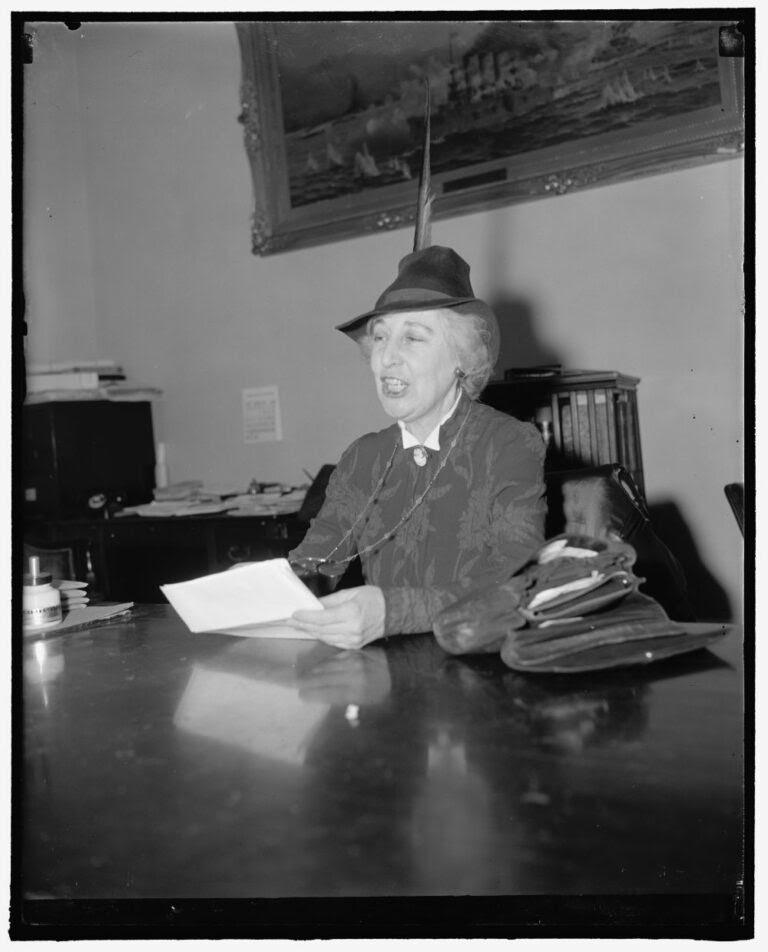

Image via the Library of Congress, attributed to “Harris and Ewing.”

Guest Author