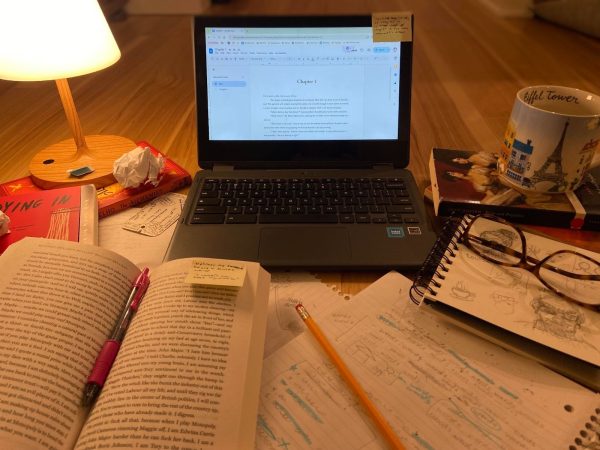

Red pigment trails behind a steady finger, forming the legs of a gazelle. Upon its completion, this wall will be scattered with paintings of graceful creatures fleeing from a bow-and-arrow bearing hunter. Some 40,000 years later, an author sits at their desk, hastily clicking the keys of their computer to meet their deadline. Humans have been telling stories long before the development of written language in many different forms. Though the method is ever-evolving, its purpose has remained the same — we feel and experience, and by storytelling, we allow others to feel and experience with us. Writing is not restricted to bestselling authors or Ivy League scholars — people of any age and experience can write. Despite this, many authors, especially younger or less experienced ones, face struggles when trying to write and publish their work.

The Bodecker Foundation is an organization that strives to empower young creatives by mentoring them in artistic endeavors, including writing. Jordan Souza, who works as program director for the foundation and is also a former Franklin English teacher, expressed appreciation for a quote by American novelist Flannery O’Connor, who said, “Nothing needs to happen in a writer’s life after [they] are 20. By then, [they have] experienced more than enough to last their creative life.” Souza believes this quote rings true for many teen authors who may feel they haven’t gained enough life experience to write a meaningful story. “If you think about it … all great books are about loss, love, grief. And those are things that you can experience at 10. I think that the biggest hurdle that teens face is thinking they don’t have anything to say, and the reality is they do.”

The first step to writing a story is getting inspiration. Dana Vinger, who teaches English and creative writing at Franklin, believes the best way to get ideas for a story is to “read all types of things: fiction, nonfiction, poetry, the back of the cereal box. Just engaging with as many stories as you can, and not just on the page, but on screen and stage as well. [Even] stories that we find in music.” Just like painters and illustrators, writers can then improve their craft by imitating work they observe. This is why it is beneficial for writers to interact with a range of stories; they can take elements from the ones they enjoy and create a scrapbook of their personal style.

After collecting adequate inspiration, it is time to brainstorm. In her article “How to Brainstorm a Story That Leaves ‘Em Thunderstruck” for Dabble Book Writing Software, Abi Wurdeman — an author and poet — recommends answering prompts about the story without stopping to think about the quality or content. She says, “Inevitably, my brain offers me some kind of answer. It may not be a fully-formed story, but it’s a step in the right direction.” Strategies like this one allow the writer to get material on the page and understand more about the story, regardless of how fully developed the ideas are.

Outlining — the process of planning out a piece of writing — is vital to building the foundation for a story to stand on. Abbie Emmons is the author of “100 Days of Sunlight” and “The Otherworld” and has a YouTube channel dedicated to helping writers strengthen their skills and craft stronger stories. In a video titled “The Quickest Way to Outline a Novel,” she suggests identifying major plot points and deciding how those moments affect the characters. Emmons also describes something called the “staircase method,” which she explains as “imagin[ing] writing your first draft [as] walking up a staircase in the dark with just a flashlight to see by, and you can only see the next three to five steps in front of you.” She continues, “If you can’t see any of it, then you’re in danger of falling down into the abyss. But maybe all you need to feel confident is to see those next four or five steps.”

Writing takes time, which is a very precious resource for students with full class loads, jobs, and extracurriculars. This is when prioritization comes into play. Vinger recommends, “Squeeze it in when you can and when it feels right, and maybe … you have to let some things go. Maybe you’re not doing club soccer, for example; you’re using that time to write.” It is still possible to add to a story without a free hour in the day. In transit from one obligation to another, a phone or scrap of paper can temporarily hold fragments of quotes or setting descriptions.

Despite how scary it may sound, sharing work is an essential part of the writing process. Niyyah Ruscher-Haqq, chair of the Young Willamette Writers program at Willamette Writers — a nonprofit organization and writing community based in Portland — says, “Having a writing community can give you what I call Artist Intelligence — meaning I can bounce ideas off other writers and talk through plot holes.” Souza shares this sentiment, mentioning, “We always think about the lonely writer, dark, depressed in a room, and I think that is limiting. I think that you can feel less alone when you share your work with others. You can feel less weird in the same way that reading allows us to be compassionate to other people.”

Sharing work in a small group builds confidence for writers who decide to publish their work. In recent years, publishing has become considerably simpler for authors not already well-established in the industry due to the rise of social media and self-publishing. When self-publishing, a writer must do the editing, formatting, designing, marketing, and pricing themselves. However, when publishing traditionally, an author works with a literary agent, who has a team to take care of the responsibilities previously stated, and who presents the book to different publishers. An alternative option is hybrid publishing, which combines elements of the previous two.

Writing is a very long and difficult process. Gathering inspiration from existing work, dumping ideas onto a page, planning out the general storyline, and having a community of writers are all factors that can help a story reach its full potential. Every writer does things differently, and it’s important to find what process works best for the individual, rather than let logistics kill the joy. Ruscher-Haqq reflects on her writing career, saying, “If I had to talk to my teen self, I’d remind them that you don’t have to write to publish. Writing can and should be fun at this stage. If you’re only thinking about your audience, you may miss the opportunity to really stretch the possibility of your story.” When asked for her closing thoughts, Souza stated that writing “[is] phenomenally brave, … you’re not going to regret it, and even if it doesn’t get sold to a big publisher, it is this amazing time capsule of who you were and what you felt at that time.”