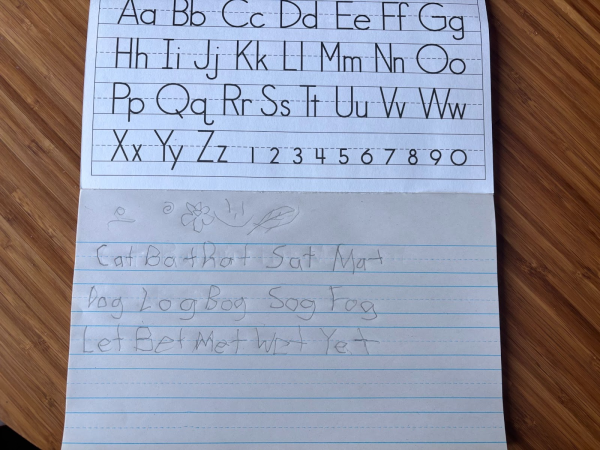

Small hands tightly grip a pencil, carefully guiding it across a lined sheet. They slightly smudge the graphite as they trace letters. This action forms neural pathways key to muscle memory. The brain develops drastically in these crucial moments of a child’s life, establishing a basis for written language. From this foundation, many forms of speech are born. From enabling political activism to scribbling down notes, writing by hand is one of the most fundamentally human activities.

Small hands tightly grip a pencil, carefully guiding it across a lined sheet. They slightly smudge the graphite as they trace letters. This action forms neural pathways key to muscle memory. The brain develops drastically in these crucial moments of a child’s life, establishing a basis for written language. From this foundation, many forms of speech are born. From enabling political activism to scribbling down notes, writing by hand is one of the most fundamentally human activities.

The history of handwriting is scattered. Erik Kwakkel is a professor at the University of British Columbia School of Information and an expert on medieval manuscripts and the production of books before the invention of the printing press. “People have used their hands to write probably since the moment they had something to write about,” Kwakkel says.

The earliest recorded writing system was etched onto clay tablets by the ancient Sumerians. They used reed pens to create triangular imprints, primarily for recording financial transactions, religious beliefs, and inventory management. The ancient Egyptians and Romans, along with numerous other civilizations worldwide, utilized handwritten inscriptions. The printing press was invented in modern-day Germany around 1440, changing the game for publications.

Kwakkel explains that “It took several decades … for [the printing press] to become the dominant medium. Even circa 1500, manuscripts were still made in large numbers, meaning that many people still wrote professionally.” Despite this groundbreaking innovation, handwritten work remained a central aspect of daily life.

As public education became ubiquitous in many regions, handwriting was taught in those spaces, ultimately cementing its use as a widespread creative and communicative tool; however, its modern role in society and education is fast changing in the digital age.

Franklin English teacher Emily Gromko mainly assigns handwritten work to her students. “There’s something about … the student voice that you can kind of sense when you read handwriting,” she says. “It’s like a piece from that person.”

Gromko argues that essays written by hand can offer new perspectives on students’ personalities, and in her experience, teenagers often approach writing in very unique ways. She says this is one interesting thing about assigning this work. “I’ve never seen so many different ways of students holding their pencils, which I think is great,” she says. This personal connection is why she prefers handing out paper to her students. She wants to hear their unique voices lost in typeface.

Gromko herself has also personally enjoyed experimenting with penmanship. “Sometimes [I write in] all caps, sometimes it’s a mix,” she says. “I love handwriting and I find it’s just fascinating.” Gromko has always enjoyed writing by hand, and she hopes to pass this along to younger generations.

In elementary school, handwriting opens new doors that allow students to write and creatively express themselves with just a paper and pen. However, as children age, they begin to type and play around with keyboards. Mae Baker, a 4th grader at Atkinson Elementary School, admits she likes to type more than to write by hand. However, she says she likes to “write and draw just for fun too.” Doodling and journaling “helps me be calm,” she explains. She also admits that if she typed it out instead of writing it by hand, she doesn’t think digitally writing her feelings would have the same effect. Baker explains that for tests, they mainly use computers, but in-class work is generally handwritten.

Gromko reflects on the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on handwriting. These traditional practices were hanging on by a thread, and the switch to online learning ultimately made digital schoolwork largely universal. Having taught for 26 years, Gromko has always had a preference for students to log essays, important information, and writing practice in a notebook, but when COVID hit, she was optimistic about this digitization. When school was confirmed to be in-person again, Gromko was excited. When she returned, many things unexpectedly went back to normal. She began implementing these organized notebook systems again, rediscovering her love for paper assignments.

Gromko explains her excitement about this switch. “When you type, you’re interacting with the machine,” she says. To Gromko, handwriting is an “art form.” Handwritten assignments also allow students to doodle on their paper. Gromko says she sees more doodles in notes now than ever. “You’re working on those ideas and also adding little illustrations, and that makes it more visual for the learner.”

Gromko has also experienced her students telling her they felt indecisive about their writing, especially when preparing for AP exams. She says many expressed their dislike of digital tests, as well as how often they went back and changed things when they typed them out.

Handwriting is an unbroken human tradition, from clay tablets to graphite pencils in and out of classrooms. While the writing tools accessible have shifted and evolved throughout time, they have maintained their relevance and ability to keep creativity alive. Whether it’s a historian who’s passionate about medieval manuscripts, a high school English teacher pushing her students to find their personal voices, or a fourth grader calming herself down by doodling and writing in her diary, handwriting persists and continues to thrive even in the digital age.