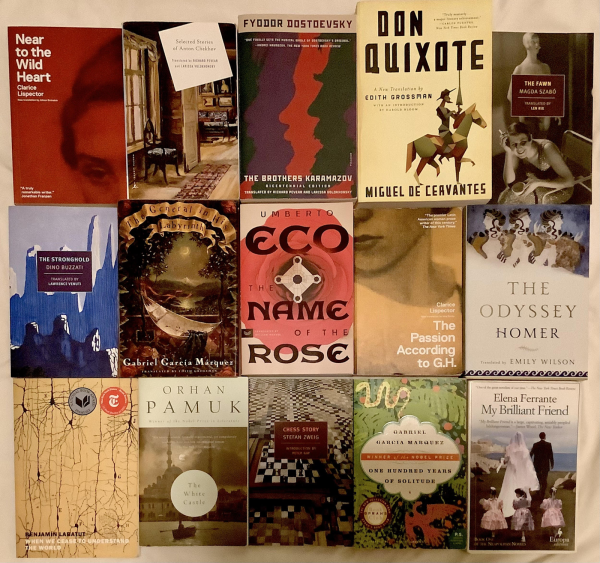

Browse any library in the United States, and you’ll find them: translated books, hiding in plain sight. From “The Little Prince” to “Pippi Longstocking,” “One Hundred Years of Solitude” to “Anna Karenina,” some of the most beloved and iconic works in the English-speaking world weren’t written in English at all. They were brought into the language due to the labor of an oft-underlooked figure — the translator.

Despite its ubiquity, literary translation is often pushed into the shadows. The role of the translator is frequently misunderstood, minimized, or simply ignored. It’s commonly assumed that translation is a mechanical process — find a word in one language, find its equivalent in another. However, translation is not merely copying — it is interpretation. Lawrence Venuti, translation theorist and English professor emeritus at Temple University who translates from Italian, French, and Catalan, explains, “The value in translation comes down to how powerful the translator’s interpretation is.”

There is no perfectly defined path between languages, only a series of carefully chosen steps. Translators walk a delicate line — staying true to the original text, while making sure that there is fluidity and depth in the translation. Nina Perrotta, editor and development manager at Words Without Borders and translator from Spanish and Portuguese, describes translation as “endless decision making.” Every word, every sentence, presents a choice that the translator must make.

“Even the same words on the page can support multiple and conflicting interpretations,” adds Venuti, “and because of that, they can support multiple and conflicting translations.” In the process of translation, the translator is responsible for carrying out the intent of the author. If the reader only knows the language of the translated version, that translation becomes their definitive experience of the text.

Translators’ decisions are crucial, as their interpretive choices directly shape how a book exists in another culture. “I always think of translated books as the fraternal twin of the original one,” says Tina Kover, who translates literature from French.

Peter Bush, a translator from Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese, and French, describes the complexity involved, explaining, “When you’re translating a style of a foreign writer who is trying to be original in his or her own language, then part of the task of the translator is to try and reflect that stylistic originality in English.” Therein lies the paradox: translators reshape literature for entirely new audiences, but are rarely seen as creators in their own right. Kover says, “A good translation of a language is beautiful. That is all the translator.” The flow and emotional resonance emerge from the work the translator does. It’s a deeply creative act, not a mechanical one.

There has been a recent push for increased recognition for translators, with efforts to include translators’ names on the covers of their work. Literary awards such as the International Booker Prize and the National Book Award for Translated Literature are also a key way to honor and promote both authors and translators. Yet translators are still largely underpaid and underappreciated. Paul Larkin, author and translator, says, “One of the problems with this widespread lack of recognition is that — academics in particular for some reason — believe they can simply publish lengthy extracts of your work without prior request, crediting, or payment.

Translators often approach their work differently. Kover does not read the book beforehand, preferring to translate as she reads so that she is “experiencing all the emotions in a very fresh way.” When working on a book that has previous translations, many translators, such as Larkin and Venuti, mentioned that they don’t read any other interpretations until they have completed their own. Larkin describes his own process via email, “I am a translator who listens to the song of the original language in the text and the author’s voice. Sounding the rhythm and cadences, and what the author’s intentions are with this song. How does it feel? What is the soul of this text? Other translators are more like sleuths seeking the perfect word that matches the original word in every single instance.” He describes both types of translators as individuals who “like to interpret, unravel, and then proclaim a mystery the translator has both solved and created anew.

In the U.S., the majority of people do not speak a second language fluently; according to a report from the U.S. Census Bureau, as of 2019, the number of people who speak only English at home is around 241 million. This monolingualism limits access to global ideas, voices, and identities. Reading works that have been translated into English is a great way to gain more empathy and insight into other countries and cultures. For translators, bridging the gap can be one of the most gratifying parts of their work. “The translator’s reward is often the reward bestowed upon the marathon runner who brings news from one city to another,” says Larkin.

“Translating is a reflection of our universal humanity,” Kover says. “It’s more important than ever when there’s so much hatred, and so many attempts to erase certain cultures and groups of people.” Despite their importance, only around 3% of books published in the U.S. are translated works. In this environment, the role of the translator becomes both essential and radical. Global literature is vital to diversity and connection.

In fact, reading and translating are deeply connected. “Translation is just as much about reading as it is about the actual process,” says Kover. “It’s about how broadly you read, and how deeply you read.” Some translators search for projects based on what they have read, and are often the ones who advocate for a book or story to be translated. Larkin believes that in this way, translators are readers who have taken a step further — they are moved by what they have read, and they take action to share it with others. He explains, “In this crucial sense, translators mirror the original author who also seeks an audience, or at the very least dialogue. It is perhaps this artistic urge that puts the lie to the pathetic canard that we translators are simply automatons who regurgitate a text in a new language. The reason why we will always be better than AI [is] our personal, human vision.”

As artificial intelligence and machine translation tools improve, there is an increased focus on automated translation. While these tools are useful for getting a rough understanding of the text, they lack the beauty and nuance of human translation.

Ultimately, translators have a unique ability to see the heart and soul of a text, and through their hard work, bring that beauty to a new readership. “It really is a deeply creative act. It’s a craft that we work for years to hone and improve,” says Kover. “There is nothing mechanical or transactional about translation. It’s a very complicated process — it’s a kind of alchemy.”