Disclaimer: Microcosm Publishing gifted a copy of this book to use for review purposes.

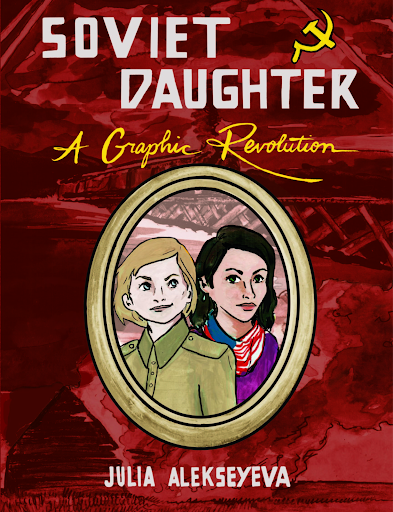

In the nonfiction historical graphic novel “Soviet Daughter: A Graphic Revolution,” author Julia Alekseyeva illustrates the memoirs passed down from her grandmother, Khinya “Lola” Ignatovskaya. Born in Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine, in 1910, and raised in Kyiv, Lola came of age in a period of political chaos. Alekseyeva weaves in an autobiographical story of her upbringing as an immigrant from Kyiv to Chicago in 1992, along with the story of her grandmother, Lola. The memoirs dive into generations of the Jewish experience in the Soviet Union, as well as the unique relationship and understanding between Lola and Alekseyeva.

Lola was the eldest in her family of six. Through the Bolshevik revolution, extreme flooding, violence perpetrated by nationalists on minority groups, and the typhus epidemic, she remained a figure of strength for her siblings. She stopped attending school in the fourth grade in order to learn how to sew to support her family, while also teaching herself how to read and write. She began work during the Stalin era, working in factories and eventually being offered a secretary position with the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs in Russia (NKVD), a key Soviet government agency responsible for internal affairs, security, and law enforcement. The NKVDwas predecessor to the Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti (KGB), which was the main internal security and intelligence agency of the Soviet Union.

Throughout the book, social themes increasingly contrast with the average politics of the United States. Lola, for example, is married twice and divorces her first husband, a process much less dramatic than it was in the US. Opposed to the often dystopian view of Soviet Russia during this time period, “Soviet Daughter” aims to explore the beautiful parts of living in a socialist country, especially in the post-revolutionary, post-civil war era, when culture and transformation bloomed.

It was a fascinating read to have such expressive insight into what it was like for the average citizen, specifically a Jewish woman, and the differences between her hardships in Kyiv versus Chicago. The family immigrated following the Chernobyl nuclear accident, which made living in Kyiv intolerable. Alekseyeva’s experience as an immigrant child allowed her to have a different outlook on the sociopolitical trends and differences between the two places. In the book, she explains feelings of alienation and ostracization similar to Lola’s life as a Jewish woman who, following World War II and Hitler’s taking of Berlin, was kicked out of the house that she was renting.

Alekseyeva shares that “The beautiful thing about being a young person and an immigrant is that you have a unique understanding of two or more cultures and can serve the role of a bridge between them.” Alekseyeva urges other young people from immigrant families to value the cultural diaspora of having this unique experience. She additionally hopes to impart through this familial retelling that “it’s okay to feel like you don’t belong … It’s a difficult place, but one that allows you tremendous and powerful growth.”

“Soviet Daughter” was finalized at 192 pages, with varied page setups using ink wash and brushed illustrations which powerfully depicted the blunt storytelling Alekseyeva had inherited through Lola’s account in her memoirs. The editing process started in 2014 and involved major revisions facilitated by Elly Blue, the editor. Blue manages Microcosm Publishing, an independent press business that focuses on highlighting marginalized voices and giving platforms to less mainstream authors. She advises that “if you want something a little weirder, a little more specific, or [you want to share] a story of someone from a part of the margins that you haven’t been reading about in the news, an independent press is a great place to look.”

“Soviet Daughter” flawlessly unites the stories of the two women’s ability to persevere and find beauty in life despite such hardships. It introduces a storyline that is not typically explored by American authors, and it emphasizes the impact of having generational conversations and a relationship with your family’s past. Looking back on her history as an author, Alekseyeva shares to aspiring authors that “[they’ll] never regret making art or writing. [They’ll] only regret never starting.”