Do you remember the first time a book truly stuck with you? For me, it was “Between Shades of Gray” by Ruta Sepetys. It may not have been age-appropriate for a 7-year-old, but, when someone left a copy in the children’s room of the public library, I was instantly drawn to the snowy-looking cover with its barbed wire border. Sepetys unflinchingly wrote about the horrors of World War II with grim, graphic descriptions of work camps and war crimes — unlike anything I’d heard of before.

In a New York Times opinion piece, author Ann Patchett wrote that reading fiction is “a vital means of imagining a life other than our own, which in turn makes us more empathetic beings.” I never thought of life as perfectly fair when I was a child, but reading “Between Shades of Gray” was the first time I read through the perspective of someone who did everything right but still got hurt. The introduction of this concept led me to approach people in positions of power more critically and increased my awareness concerning the brutality of war.

In the age of social media, profitable algorithms often create echo chambers of agreeing viewpoints, feeding users content that aligns with their beliefs and interests. This poses the risk of someone becoming so immersed in their online space that they lose track of perspectives that differ from their own. Even if those perspectives are presented, it can often be in a mocking, insincere way. Books are a way to challenge this bias. Nuanced, diverse stories presented for genuine consideration help humans grow intellectually and become more empathetic towards others. In a world with a plethora of issues and injustices, knowing you’re not alone and being aware of the privilege you have is incredibly important. While reading a book cannot fix problems, it can offer solace, solidarity, and perspective.

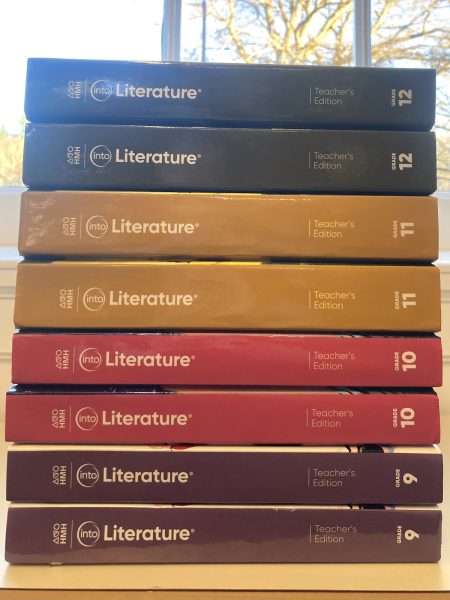

In only four years of high school, the question of which texts to teach in order to help students gain both knowledge and empathy is an important one. For some students, these may be among the last literary texts they’ll take the time to read as they exit high school and move into their adult years. Recently, Portland Public Schools (PPS) bought the standardized English Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH) textbooks and encouraged English teachers to use them as their curriculum. Part of the appeal of textbooks is an understandable desire for alignment. With more than 44,000 students in the district, teachers must have consistent standards and expectations to ensure every PPS student graduates with the necessary skills.

In any curriculum, this skill-building is essential; education is meant to give students the insight and experience they can apply to future academics, employment, and everyday life. PPS states on their website that the 9-12 English Language Arts (ELA) courses aim to develop students who are “resilient and adaptable lifelong learners.” Their other listed goals are that students come to be “inclusive and collaborative problem solvers” and “inquisitive critical thinkers with deep core knowledge.” These are worthwhile aims, designed to create successful students; however, some teachers are not convinced that the HMH textbooks are the best way to reach those goals.

Literature is not guaranteed to reach everyone. Reviews of any book range from five-star raves to one-star rants, and what is inspiring to one person may be boring to another. Texts, no matter how much literary value they hold, will not have the same relevance in every classroom. Therein lies one of the problems with textbooks — they can preserve events and beliefs, but they cannot respond to them.

Teachers who see students daily and hear what captivates, irritates, and intrigues them are uniquely positioned to select texts and tailor assignments to meet the needs and interests of their classroom community. For many teachers, creating their own curriculum is more than a plan; it’s something they value doing. Franklin English teacher Kawanna Bolden said that having a standardized curriculum “strips away pieces” of what she loves about her job. Bolden highlighted that, in her experience teaching, a high level of engagement “only comes from the teacher doing the real work to engage the students.” She explained that the heavy focus PPS puts on using standardized textbooks over teacher-curated curriculums feels like the district wants “workers not teachers.”

Elisa Wong, an English teacher who has worked at Franklin since 2005, said that, when teaching with only curriculum from a textbook, “You cannot be responsive to students in a cultural way, in an individual way, in a current events way. You just cannot be responsive to your students and to the world around you when you have a textbook.” For PPS to achieve their goal of training students to think critically about the texts in front of them and the themes and problems within, they need to have students who are excited about the subject matter.

English teachers need the opportunity to provide students with texts that make them think, question, and want to keep learning. Beliefs inform actions, and being well-informed on the facts and feelings behind a viewpoint or event is key to developing empathy for differing perspectives. HMH states that their Into Literature Curriculum — created for grades 6-12 — is filled with “diverse, culturally relevant texts.” The New York University (NYU) Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development conducted “An Evaluation of Cultural Responsiveness in Elementary ELA Curriculum,” which examined HMH. Using their Culturally Responsive Curriculum Scorecard — which specifically measures how well cultural identities are represented and diverse authors are included — researchers found HMH to be “Culturally Insufficient and Culturally Destructive,” meaning it failed to present “marginalized cultures in ways that are complex, nuanced, and dimensional.”

Having culturally responsive texts does not mean excluding works from the past, which can contain important messages about humanity, are records of history, and capture the mentality and issues of the time they were written. For representation to be nuanced, different cultures and ways of life should be presented as more than stereotypes, and issues should be discussed with appropriate context. As NYU Steinhardt’s study explained, “While it is not possible to represent every aspect of all people’s cultures in a curriculum, it is important to evaluate the balance of what is included.” Including more diverse perspectives in a curriculum increases the chance that texts will resonate with and engage a variety of students.

Andrew Cohen, a professor at Portland Community College and their Humanities and Arts Council Chair, stated that engagement is the baseline for teaching: “Unless you’re engaging them, I don’t think you have a chance.” Pam Garrett, a teacher at Franklin since 2005 who has taught all four levels of English, agreed, “There’s nothing that motivates a student more than giving them a choice.”

A study done by Gallup, an analytics and advisory company, found that student engagement impacts performance, reporting that engaged students were 2.5 times more likely to report that they get excellent grades and do well in school. This also translated to future performance, as Gallup found that engaged students were 4.5 times more likely to be hopeful about the future than their peers. Students who are engaged demonstrate the very qualities that PPS hopes their English classes develop. “They’ve got to feel like there’s a reason they’re working with you on something that feels important and meaningful,” said Cohen. “I find it really hard to imagine that a textbook can do that.”

PPS wants to have successful, academically challenged students, and to do so, those students need to be engaged. Ultimately, English is not meant to be taught from a textbook; it’s the connections and conversations that spring from literature that make teaching the subject so valuable. To truly help students become critical thinkers and insightful human beings, they need to be allowed to learn and create differently. That is where standardization cannot succeed. Giving teachers control over the assignments and texts they choose can give students a better chance to build key skills, develop a love for literature, and show empathy for others.