The roaring 20s are over, and the 1930s and 40s are just getting started, so put down your feathered headbands and lock up your speakeasies. It’s time to take out our tilt hats and listen to swing jazz on the radio. This issue of “A Brief History of Portland” will cover a range of topics from the Great Depression and World War II (WWII) to the Memorial Day flooding of what was, at the time, Oregon’s most racially diverse town.

1929 marked the start of the Great Depression, and like people nationwide, Oregonians were feeling the impacts of the nation’s economic downturn. At this point, Oregon and Washington alike had not recovered economically following World War I (WWI). Due to high unemployment and poverty rates, Portland had completely emptied its emergency fund by 1930, and in March of 1933, approximately just over 13% of Portland’s population was receiving financial aid from the government.

Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1932 and soon implemented his New Deal programs to get people back into the workforce. The Works Progress Administration put 25,000 Oregonians to work primarily through small-scale projects that created several now-iconic landmarks in Portland, such as Waterfront Park, Rocky Butte, Council Crest Park, and the McLoughlin Promenade. The administration also improved roads and public parks, cleared brushes, and installed street drainage systems.

Despite the improvements made by the New Deal, the Great Depression wouldn’t be quelled until WWII. As the U.S. prepared for the second major war of the century, factories began to create everything they could for the military. During this time, finding an escape from the war was difficult at best. Civilians worked long hours to keep their country afloat, and the few moments of joy civilians found often led back to the war. It was as if everyone in the media was utilizing propaganda. Going to the theater meant watching a newsreel, which was all the latest updates on the war; listening to children’s stories on the radio meant hearing about how “justice always prevailed” and how to help the war effort by buying war bonds or saving resources like water and gas.

WWII also marked significant social shifts among youths, with things like delinquency and sex work on the rise. In 1943, the Portland Police Bureau published a report that there was a 500% increase in delinquency compared to 1941, with many youths getting involved as young as 13 years old.

Other problems arose during this time among the adults who had moved to Portland to help with the war effort. Loneliness rose, and with it, heavy drinking, as many of those new to town had left their communities. Women, in particular, had an incredibly hard time. They were expected to earn a second income, as well as run the household, including cooking, cleaning, and caring for the children.

The start of WWII also ignited new paranoia; this time, it was targeted at Japanese Americans. Not to say that racism of this sort was new, but due to the war being fought in the Pacific Theater, much distrust and anger was directed towardsdirected towards those of Japanese descent in Oregon, all of which boiled over into what we know today as incarceration or concentration camps. Japanese immigrants would not be allowed American citizenship until 1952, and “there was resentment towards the success of Japanese and Japanese American farmers,” says Erin Schmith, the mmarketing and ccommunications ccoordinator at the Japanese American Museum of Oregon.

In 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which according to the NNational AArchives, “authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to ‘relocation centers’ further inland — resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans.”

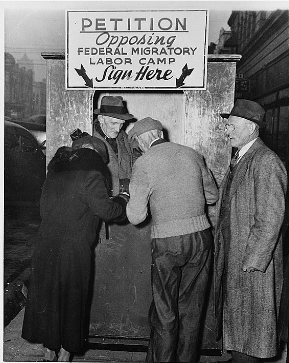

Oregon had one such camp, a farm labor camp in Eastern Oregon, where workers were brought to help with the shortage of agricultural laborers. In addition, Oregon had one temporary detention center, where Japanese Americans were held before being transported to one of the permanent camps in Idaho or California, located at the Portland International Livestock Exposition, now known as the Portland Expo Center.

As incarceration ended, some Japanese Americans were able to make it back to their previous houses, businesses, or farms, but many lost everything that they had. Life afterward was difficult, even for those who had places to go. Japanese Oregonians, known as Nikkei, created a town in Portland called Nihonmachi, a Japantown. But during incarceration, the town was lost completely, so for those who returned to Portland, “it was very difficult for the first-generation Nikkei to integrate into society after losing Nihonmachi,” Schmith states. They could no longer “cater to other Japanese-speaking people in a concentrated area, and they became more reliant on the younger generations.”

Despite this, several Japanese-owned businesses in Portland survived and are still around today, most notably,, because of their proximity to Franklin, Kern Flower Park Shoppe on 67th and Holgate.

Jumping back to the start of America’s involvement in WWII, before America formally joined the war, President Roosevelt passed the Lend-Lease Act. According to the NNational AArchives, “This act set up a system that would allow the United States to lend or lease war supplies to any nation deemed ‘vital to the defense of the United States.’” However, this changed when America officially joined the Allies, and white men began to leave for the war. During this time, people of color and women gained access to labor markets that white men previously occupied.

At this same time, the African American community developed a campaign meant to push back against the racism faced on the home front while also fighting racism and fascism in European and Pacific TTheaters,, known as the Double Victory strategy. According to the Oregon Secretary of State’s website, “The campaign called on Blacks to loyally serve the nation while emphasizing the contradictions between America’s professed values and its behavior with respect to racial discrimination.”

Despite pushback, some progress was made in allowing Black people into the U.S. military. In 1941, a policy stated that “African American strength in the Army would reflect its percentage in the population (about 9%) and that African American combat and noncombat units would be formed in every branch of the service,” according to the Oregon Secretary of State website. Unfortunately, by 1943, rising tensions saw the worst race riots in the country since WWI.

The population of African Americans in Portland shot up during this time, as many people were migrating from the Southern states to larger cities across the country’s Northern states. According to the Oregon Secretary of State’s website, Portland’s African American population went from “under 2,000 before the war to over 22,000 in 1944.” At the same time, Portland’s white population grew by nearly 160,000, leading to more tension between the two groups.

There were more problems than just social tension; with such a quickly growing population, it was very difficult, especially for Black Americans, to find places to live. To solve this housing crisis, a new project was started that, at the time, was the largest that America had seen. It was called Vanport and was named after the cities surrounding it, Vancouver and Portland. During the early 20th century, Portland had a reputation for being one of the most prejudiced cities in the West. However, the man who ran the project in Vanport, Henry Kaiser, didn’t only employ white men. Because of this and the vast array of jobs in the Kaiser shipyard, Vanport became the most racially diverse city in all of Oregon.

After the war was over in 1945, many of the African Americans who had settled in Vanport chose to stay. However, on Memorial Day, 1948, the Columbia River flooded, covering the town in 15 feet of water and leaving nearly 6,000 African Americans homeless. Though some Portlanders thought this flood would drive out the citizens they no longer wanted in their state, othersothers rushed to help. Coordinating with the Red Cross, Portland started a campaign to house and care for all residents who had lost their homes.

Though it would be many years before segregation was finally made illegal, an Oregon History Project titled “The Vanport Flood,” written by Michael N. McGregor, states that “the Vanport flood in 1948 had unexpectedly forced Portland’s white residents to reckon with their racist housing practices.”

Oregon experienced many changes during the WWII and the Great Depression, but the state has always bounced back and will continue to do so despite it all. Though our state and city’s history is full of bigotry, if you look, you’ll find many places where different groups have found community and pushed through the challenges they previously thought impossible to endure.