In 2021, among people ages 18 to 74, women made up half (51%) of the total U.S. population but only about a third (35%) of people employed in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) occupations, according to the U.S. National Science Foundation. The STEM workforce is widely known to be a predominantly male-dominated field of work. This can be attributed to the environment children are raised in, and how exposing them to certain elements can dampen their confidence in different subjects.

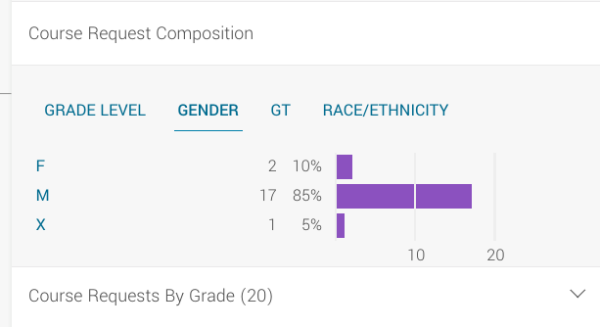

At Franklin, this gender disparity is reflected in STEM Advanced Placement (AP) classes. Out of the 11 STEM-related AP classes Franklin offers, only two have a percentage of more female than male students. AP Statistics has the highest rate of female students, at 54%, while the biggest disparity is in AP Computer Science Principles, with a startling 10% of female students. “I have taken an AP Physics class where there were only seven girls out of 40 students,” an anonymous female junior at Franklin comments. It is important to remember that 49.97% of Franklin students identify as male, 47.54% as female, and 2.48% as non-binary. There are about 50 more male-identifying students at Franklin than female in total.

Stereotypically, men are more likely to be seen in the STEM field. When young girls grow up watching male scientists like Neil deGrasse Tyson and Bill Nye in their elementary and middle school classes, it can give them the impression that STEM is only for men. There needs to be equal representation in the STEM field for people from all aspects of life. Girls need strong role models growing up so their dreams feel achievable. Early exposure to STEM careers is important, and when equal representation of all genders and races isn’t displayed to children, it can create stereotypes and unconscious biases for them and their peers. David Stroup, the AP Physics teacher at Franklin, shares, “I think some female students may have been given the message that STEM studies are more for boys, which is a pity — we need more women in STEM fields.”

Many female students often self-select out of male-dominated classes due to a lack of representation. Being a female student in AP STEM classes in high school can feel belittling when you’re a minority in the class. The same anonymous female junior at Franklin states, “Growing up as a woman being told that STEM courses aren’t for you [and] seeing the media always showcasing men in those roles … you tend to not want to participate.”

In multi-level classes at Franklin, such as AP Calculus and AP Physics, there is a significant decrease in female students as the level of the class progresses. Between AP Calculus AB and AP Calculus BC, the percentage of females enrolled drops from 36% to 25%. Similarly in AP Physics 2 and AP Physics C, this percentage goes from 40% to 24%.

“Certainly the students who are accessing advanced coursework across the system are traditionally not historically underserved students,” says Chris Brida, the director of Career Technical Education and Pathways at Portland Public Schools (PPS). Brida handles the AP and International Baccalaureate (IB) programs in all PPS schools. “I think that, especially in your generation of students, sometimes there’s a mismatch between your aptitudes and the things you’re exposed to,” he says.

He goes on to explain a new position in every PPS building that offers advanced coursework: a Learning Acceleration Instructional Specialist. “The role of that person is to help support historically underserved students, both in accessing advanced coursework classes like AP and IB, and being successful in those classes,” explains Brida. Stroup emphasizes the importance of teachers and administrators to help close the gender disparity in STEM, stating, “I work to recruit people of all genders and to make girls — who are underrepresented — feel welcome in my STEM AP classes.”

When asked about his hopes for the future of equality in STEM, Brida concludes, “I think the goal always when we’re talking about advanced coursework is to reduce as many barriers as possible for students to access it, right? So that’s both gender barriers and certainly racial barriers.” Racial disparities in AP STEM classes are an equal if not larger problem than the gender disparity in STEM.

In the future, schools need to continue to encourage underrepresented students, including women, to enroll in AP STEM classes and help resolve the disparity. Recognizing this disparity is the first step in the right direction to make this change. It’s also important to raise awareness around the disparity and encourage women and other underrepresented groups in the STEM field to pursue their interests without hesitation. Creating opportunities for all students to feel supported in their STEM classes can help show that this field is attainable for everyone. That’s why it’s especially important to develop and incorporate systems and practices into STEM courses and programs that can help retain underrepresented students who may be put off by feeling isolated in these settings. By making these changes, it makes for a more inclusive, diverse, and innovative environment where every student can have the chance to thrive.