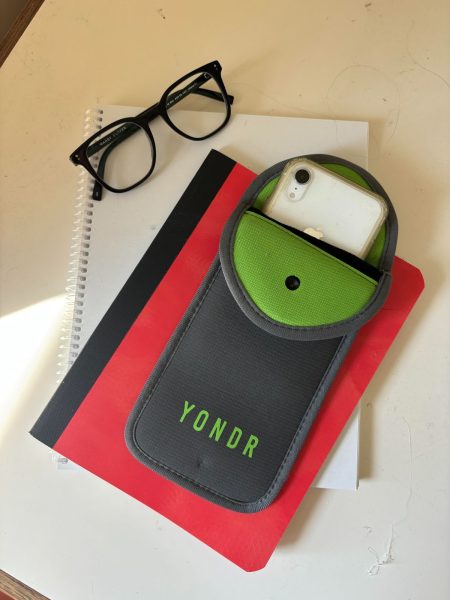

Portland Public Schools (PPS) is considering a districtwide cell phone policy. As part of this plan, Yondr pouches are being implemented in certain schools. The Yondr pouch is a magnetic pouch that stores a cell phone and can only be unlocked by Yondr-issued magnets provided by a school. Beaumont Middle School, Grant High School, and Cleveland High School are being used as pilot schools to test the effectiveness of this phone policy and determine if it could be implemented elsewhere. There have been mixed reactions to these pouches, from students and teachers alike.

Yondr pouches cost $25 to $30 per student. Grant spent more than $60,000 on over 2,500 pouches after receiving a $20,000 discount for being a pilot school, according to a KGW-sourced PPS purchasing order.

Some teachers are in favor of Yondr pouches because they create a phone-free environment in the classroom. Since not all teachers use the same policies in their classrooms, students often see a substitute as an opportunity to not follow the class phone policy. A substitute teacher at Grant discusses a reason for her initial liking of the new phone policy, saying, “Students are always going to take advantage of substitutes.” Using Yondr pouches means it is easier for her to ensure students are abiding by the phone policy. On her first day as a substitute at Grant this year, she could immediately sense the difference the Yondr pouches had made. “The class was really engaged in what they were doing, and there weren’t [any] kids wandering in and out of class,” she says.

The Yondr pouches have also eliminated the flustered period at the beginning of classes when students reluctantly move to the front of the class to put their phones away. “These things that should be simple and take five minutes, wind up taking half an hour,” comments the Grant substitute. Removing this period gives the teachers and students more instructional time and allows the class to begin sooner.

When PPS announced the new Yondr policy over the summer, it came as a surprise to students. “I was shocked when I first heard about the Yondr pouches being implemented,” says Alina Luu, Cleveland’s District Student Council representative. “I didn’t think that the usage was that big of a problem to have the need for something like the pouches,” Luu continues.

Some students say the new policy is a violation of their rights, or that it is unjust to confiscate their personal property. “It’s mine. … I should be able to keep it,” says Josephine Maloney, a junior at Cleveland. The Grant substitute feels differently: “It’s not punishment; it’s not taking away a right.” In her view, teenagers are often rebellious and cannot grasp when things are being done for their benefit. “[Phones] take away from instruction in ways you may not appreciate as a teenager,” she says.

However, the policy also makes it harder to access class material and makes small things tedious. “You can’t scan QR codes, take pictures of assignments to submit in class, or make social media posts for classes like leadership,” Luu says. Removing phones has the intention of making classes more productive but has been found by many students to do the opposite.

“Students are texting each other in other classes … you’re a teenager and it’s normal; there was passing notes when I was in high school,” says the Grant substitute. She acknowledges teenagers are prone to misbehavior and believes there should be a firm system in place to control it. “Students really need to be held accountable,” she says. If a teacher makes an exception to the phone policy for some students, others might think the exception applies to them as well. “I think locking them up is clean, … and it’s easier.”

Though phones have been removed from classrooms, focused work time is not guaranteed. Students have resorted to other forms of technology during class. “The other day, I watched this kid in my anthropology class scroll on [Instagram] reels [on their Chromebook],” says Maloney. The lack of phones has created new issues with Chromebooks, since many social media sites are accessible on school-issued computers.

In addition to using Chromebooks as a phone alternative, Maloney describes how most of her friends avoid using their Yondr pouches completely. “To be honest, I just tell my teachers I keep my phone in my car,” says Maloney. She says her friend group puts their old iPhones in their pouches so it appears their actual phones are inside. They do this to use their phones during lunch and avoid the line to unlock them at the end of the day. “I don’t know a single person that actually puts their phone in the pouch … everybody has found a way around it,” agrees Luu. “There are definitely some people that do, but it is a slim percent compared to the people who don’t,” Luu continues.

Some schools, like Franklin, have implemented less strict policies surrounding cell phones. The Franklin policy includes phone pouches in each classroom and a three-strike system. If a student violates the phone policy three times, their phone is sent to the office, where it must be retrieved by the student’s parent.

“A lot of it needs to be on school administration and the district. … They have to be really clear about guidelines and really consistent,” the substitute says. When told about Franklin’s policy, the substitute remarked that it was too much work for teachers. “It’s just not something teachers should have to deal with all the time,” she says. Policies should be created and enforced by the district, not teachers, the substitute argues. When phone policies are put in the hands of the teacher, it becomes a large, and often unfair, responsibility. “When schools try to implement things as the year goes on, teachers get busier and things get harder to implement.” Still, she wonders if the expense of Yondr pouches for the entire district would be worthwhile.

Some students feel that the previous system was sufficient for controlling phone usage. “There is no significant advantage to the pouches over other policies like the caddies,” argues Luu. “[Phone caddies] had the same effect as the Yondr pouches at a cheaper price.”

The substitute suggests there may be alternative ways to create phone-free schools in Portland. “I just think there needs to be a blanket, consistent thing that becomes part of the culture of your experience [in school].” She goes on to explain that schools should cut out the three-strike method and skip straight to sending the phone to the office. This way, classrooms would be phone-free, and the district would not have to spend $60,000 per high school. “The only reason the pouches seem effective is because of the enforcement that will happen if a student is seen with their phone out, not because of the pouches themselves,” agrees Luu. The policy in place is not the effective part, but rather the reinforcement and discipline around it.

The PPS Board of Education recently received a report on the status of the district-wide phone policy. They most recently discussed a draft of this policy on Monday, Oct. 21. Staff released a survey where the responses would influence the policy making. Those questions included what students used their phones for during school, whether cell phone use should be allowed during passing periods and lunchtime, and whether the student’s school already has a policy. They gained more than 2,100 responses from high school students.

Students and teachers have expressed that there should be a more effective, district-wide policy, emphasizing the need for accountability and support from school administration and families. There is also potential for statewide policies to address phone usage in schools. For now, Franklin students and families must wait to see how the Yondr pouches work at Cleveland and Grant. What will the district decide to do?