Note: This article is a part of the six part series “A Brief History,” to find the first edition about Portland’s Indigenous communities, visit fhspost.com.

“There is a peculiar fascination connected with the reminiscences of the early life of individuals, societies, communities, and nations,” states T.H. Crawford in his historical sketch of the public education system in Portland from 1847-1888. This fascination is timeless; through each passing year, it’s possible to find new people who want to share stories, thoughts, and queries. By doing so, more interest in the past is sparked. Crawford continues, “To weave these detached and frequently vague outlines into an interesting yet truthful narrative is the province of the historian.”

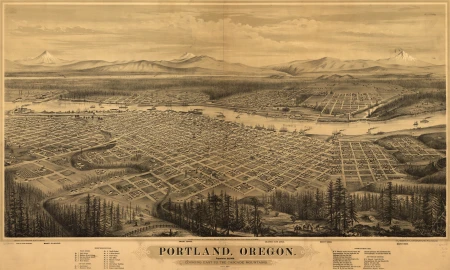

For this edition of “A Brief History,” we will dive into the lives of some of our first Oregonians. From the United States acquiring the territory of Oregon in the late 1840s to the end of the 19th century, we’ll be focusing on the first settlers to arrive from the Oregon Trail and the economy they set up, as well as looking at the unique issues that came with starting a public school system, and finally the exclusionary laws that were put in place to try and maintain Oregon as a white-only state.

The Oregon Trail’s primary years lasted from the 1840s to the 1860s and brought people of all different backgrounds to Oregon. From farmers to business owners, whole families took a five-month trek across North America to see what the Willamette Valley had to offer. Many Oregon students have played the silly Oregon Trail game in schools, trying to get their party all the way to Oregon without everybody dying of dysentery. Still, all of the issues posed by the game were challenges people had to worry about back then.

Approximately 400,000 people came along the trail from all over central North America, such as from Iowa, Nebraska, and Missouri. As they got closer to the Oregon territory, some groups split off, instead heading to Puget Sound in Washington, Utah, California, or other western territories. Once wagon parties arrived in Oregon, they were treated with camas root, berries, salmon, and the Willamette Valley harvest, which provided plentiful amounts of food for the winter months.

To attract people to Oregon, the Organic Act of 1843 was passed; the establishment of this act not only designated Oregon’s provisional government, but also offered 320 acres of land to any white male of at least 18 years of age, and 640 acres to any married couple. As of 1850, approximately 800 people lived in Portland, and this number grew slowly but steadily as more and more people were attracted to the lush farmland and trade opportunities that Portland provided.

A wholesale business by the name of Ladd, Corbett, and Failing turned into a bank that held Portland’s economy on its shoulders, selling land to real estate investors for large amounts of profit. Actions like this led to the booming economy of Oregon and the Pacific Northwest. Due to this boom, workers, specifically those with specialized skills, started organizing themselves into unions. These unionized workers were set apart socially from their non-union counterparts and tried to avoid being lumped together with them.

As the population grew, so did the rising need for a public schooling system. “Many city and state leaders in the mid to late 1800s thought that most people didn’t need much formal education,” states John Killen, a now-retired history reporter and breaking news, city, state, and assistant sports editor for the Oregonian. “They thought the working class needed only basic math and reading skills, at most. Higher education, even high school level education, was something they seemed to think that only the upper class needed,” Killen explains. This belief led to the only schools offered being private, as most people either didn’t think further education was necessary or simply didn’t want to pay for a public education system.

“It wasn’t until about the 1870s and later that the idea of public education began to pick up support, and Portland’s public school system began to get a foothold,” Killen states. Despite public opinion being swayed, it wouldn’t be until the 1880s that the first public high school was constructed. After finally establishing a public school system, Oregonians would find another significant issue with implementing more schooling. This issue? Mischievous boys. In Killen’s Throwback Thursday, he states, “Truancy was common, and teachers often had to track down students, who might be found playing cards.”

Along with this, it would be frequent that these boys would run up to windows and tap on them to distract students, only to run away before getting caught. “I suspect it was related to the culture of the day. Up until the first public schools opened, most boys probably had a lot of free time, and Portland was probably a fairly adventurous place to live,” Killen notes. “Being told you were going to have to spend five or six hours a day in a classroom when you had previously been able to be outside and able to run around may have made for a pretty hard adjustment.”

Despite officially having public schools, they were still segregated, though not for long. In the 1860s, a Black man named William Brown sued the city because they wouldn’t allow his children to attend school. This lawsuit led to the opening of Portland’s first school for people of color referred to as the “Colored School,” but for several reasons, this school failed. Eventually, in 1872, it was decided that this school would be defunded and that they would integrate it with the all-white schools surrounding it.

It was not easy to settle in Oregon as a Black person, but despite all the challenges, many persevered anyway. “Prior to the arrival of the transcontinental railroad in Portland in 1884, Black Americans were few in number and widely dispersed across Oregon,” states Zachary Stokes from Oregon Black Pioneers. “There were no Black communities to speak of, so Black people’s economic and social survival depended on the relationships they formed with their white neighbors,” Stokes notes. This left many Black people in a precarious position; with the passing of the 14th Amendment, Black people were no longer legally excluded from Oregon, “but segregation and poverty were the reality for most Black Oregonians,” Stokes continues.

Prior to the 14th Amendment, however, many Black Oregonians had to worry about the extensive exclusionary laws and whether or not they would be enforced. From June of 1844 until July of 1868, Oregon went back and forth between permitting and prohibiting black emigration six different times. After Black exclusion was legally ended, discrimination was still frequent and continued for a long time, similar to many other parts of the United States at this time. Stokes states that “Indian removal, the lynching era, Japanese American internment, and the Chinese Exclusion Acts all happened within the 75 years after this amendment was passed.” Racial segregation in Oregon was not made illegal until the 1950s, nearly 100 years after the state joined the union.

Despite knowing that it was illegal and even dangerous to move to Oregon, many Black people made the journey and did it nonetheless. “Their courage helped create the first generation of Black Oregonians and proved to white people that Black people could be successful, independent, and dignified,” says Stokes.

Many issues arose during Oregon’s formative years, from dangerous fires to rowdy boys, but despite all the hardships, these events brought forth what we know today as Oregon. History will continue as we move through the present, and as it changes, so will its interpretation.