Content Warning: Discussion of violence, discrimination, and mistreatment of Indigenous peoples throughout American history

The first communities of people arrived in the Americas many thousands of years ago, and they found places from the northernmost corners of Alaska and Canada to the southern tip of Chile to settle. These ancestors, who we now know as Indigenous people or Native Americans, migrated to the Americas via the Bering Strait, a land bridge that previously connected Eurasia and North America. They made their homes in communities across the Americas and developed unique cultures, spiritual beliefs, and traditions that have been passed down for generations.

This is the first of six parts about the history of Portland, where each issue of the Franklin Post will hold a new addition. In this series we’ll be exploring how Portland developed into the city that it is today, which we can’t do without understanding who was here first.

There are nine federally recognized Indigenous tribes in Oregon. These tribes range from the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, to the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, to the Klamath Tribes, and many more. While there are only nine tribes that are federally recognized, many others still exist, and — like in the case of the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw — some confederated tribes consist of multiple tribes that all share one reservation along with the benefits of being federally recognized.

This article will focus on the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde who live throughout western Oregon, as well as in parts of southwest Washington and northern California. According to the Oregon State Legislature website, over 30 tribes and bands live within the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, including the Kalapuya, Molalla, Chasta, Umpqua, Rogue River, Chinook, and Tillamook tribes. The history of Indigenous people throughout the Americas is heavy and heartbreaking and rich, and their history in Portland is no different.

In 1853, after decades of mistreatment, violence, and disease, the Indigenous people of the Rogue River Valley negotiated with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to create the Table Rock Reservation. The land that was given to the Indigenous people did not have enough resources for all its occupants, nor was it safe from the colonizers in surrounding areas. The Southern Oregon Historical Society (SOHS) explains in their summer issue of 1996 more details around how the reservation failed to protect against the discrimination and attacks of white migrants. “[Table Rock] proved inadequate … to stop the machinations of self-styled ‘exterminators’ who murdered and massacred Indians and then repeatedly provoked them to retaliate.” One of these attacks led to the starting of the Rogue River Indian War, which claimed the lives of approximately 250 Indigenous people and lasted eight months.

When it was established, Table Rock was strictly a temporary reservation, so, during the late 1850s, an “Indian agent” by the name of George Ambrose, whose job it was to interact with Indigenous people on behalf of the United States government, removed the Rogue River and Chasta Tribes and forced them to march 263 miles over 33 days to the new Grand Ronde Reservation. This has become known as the Rogue River Trail of Tears. Ambrose kept diary entries during his trip, which are publicly available and free to read on SOHS’s website. Editor of SOHS, Stephen Dow Beckham, summarizes Ambrose’s entries and what they reveal about the impacts of the migration, stating, “Left behind were the bones of parents, grandparents, and ancestors, ages-old villages and fisheries, and a way of life well-tuned to the rhythms of a beautiful land.”

Once they arrived at the new territory, the people in the Grand Ronde reservation were established as the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. As a reservation, the people of Grand Ronde were a federally recognized nation. This recognition allowed them to self-govern, helping them to be able to better preserve their culture and create their own policies. It was 87 years later, in 1944, that the US government began to get rid of its agreements with the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. This started a process known as “Termination,” and, in 1954 under Public Law 588, Congress affirmed that the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde were assimilated and no longer required federal assistance programs such as financial aid and other social services.

The version of Public Law 588, also known as the Termination Act, that was passed was the second one proposed. The original version had been rejected by the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde before being revised and reproposed. Despite being rejected again, Indian Superintendent E. Morgan Pryse submitted the law to Congress — stating that the tribes had agreed to it, which they had not — and it was then passed in March of 1954.

This act was devastating for many reasons. It completely got rid of their federal recognition, so they were no longer able to self-govern, they lost all of their land, and it removed all of the government’s obligations for federal assistance to the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. Once the tribes were “terminated,” the government paid individuals for the land that they had taken. “We got our payments, you know they paid us a little dab of money for our reservation which was nothing compared to what they took,” says Margaret Provost, a Grand Ronde Tribal Member, in a video posted by Patty Jenness on YouTube. “Some people got $35, some people got $500, and that was our payment for all of our land here.”

Though the Termination Act abolished their reservation, forcing the Indigenous that lived there to either purchase their land or move, members of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde were able to retain some of their rights. Both fishing and hunting had never been discussed during the creation of their treaties nor was it mentioned in the Termination Act, so they were able to keep their rights to practice both. Along with this, their cemetery was kept as community property.

After the Termination Act was passed, many of the Indigenous people living in the Grand Ronde reservation had to move. Provost states that, “People … moved and we didn’t have the close bonding like we did with family, and we still don’t now.” In 1956 the Grand Ronde reservation was officially closed, and the tribes that lived there were left without access to healthcare, government welfare, or education. It was at this time that Congress passed the Indian Relocation Act, a federal law that encouraged any Indigenous person who lived on or near a reservation to migrate to urban areas by removing resources from their land, and thus pushed the assimilation of Oregon tribes into surrounding communities.

It wouldn’t be until the early 1970s that Congress would try and reverse the effects of this termination. This was done through laws such as Public Law 93-638, also known as the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, which gave tribes more control over their reservations and allowed for better funding towards building schools on or near reservations. The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde state that, “On November 22, 1983, with the signing of Public Law 98-165, the Grand Ronde Restoration Act, [reversing termination] was accomplished.”

Today, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde are once again a federally recognized tribe along with the eight others in Oregon, but the impacts from the treatment, laws, and discrimination that white people have enacted on the Indigenous people of America are still felt both nationally and locally.

One way this can be felt is through the quality of education that Indigenous youth get throughout the country. Franklin sophomore Drea Phillips describes how it can be harder for Indigenous students to get scholarships in comparison to white students, explaining, “Not many Indigenous people get handed scholarships … due to the lack of funding to the schools that Indigenous individuals attend.” Phillips continues, “In order for Indigenous [people] to have a good or decent education, we [have to] leave where we are from … which takes us away from our culture and families.”

There are more problems Indigenous communities face beyond educational inequalities, especially in a city that used to be so segregated and in many ways continues to struggle with diversity. “I often feel alone. Alone because I don’t see very many Native American people when I’m out and about,” Phillips says. “But when I do see a Native person in public, it’s always a great feeling.” Franklin’s Schools Uniting Neighborhoods (SUN) School Program hosts a Native Affinity group for Indigenous people of any background to come and connect with peers. According to Phillips, they usually have an attendance of around eight. “We all have such good connections with each other because we know we won’t see very many Native people at [our] schools and jobs.”

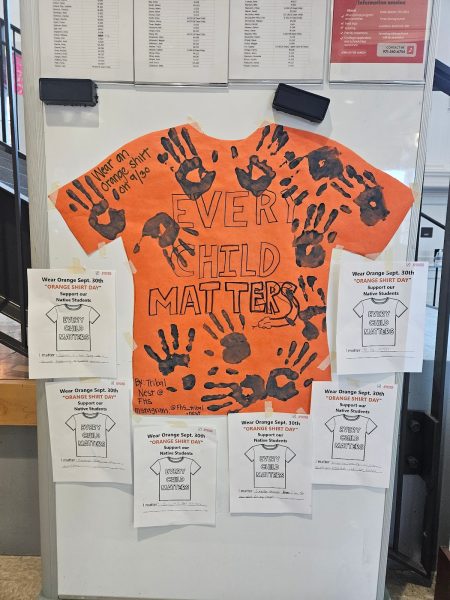

There is still a lot of work needed to be done to restore what was taken from Indigenous people, including the Land Back movement and monetary reparations. Another way that Indigenous people are looking to right the wrongs they’ve experienced is through the Orange Shirt Day movement. From the mid 1800s to the early 1900s, America required all Indigenous people to attend residential schools. These schools forced Indigenous children to give up their language, religion, and cultures. While things like affinity groups can help build up communities, it’s important for everyone to listen to Indigenous voices and to take action in support when possible. In the words of Phillips, “My existence is my resistance! Land back! Bring our children home.”